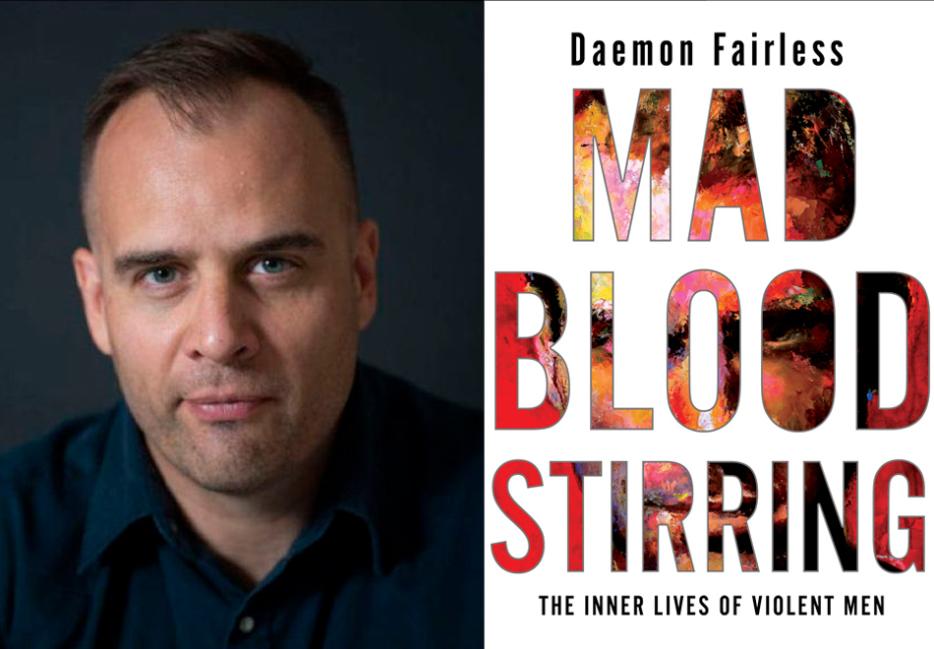

Daemon Fairless begins his debut book of non-fiction, Mad Blood Stirring, with a description of a fight in a Toronto subway car, where he head-butts a verbally abusive, very drunk man who has become a potential threat to his wife, and other people on the train. At the time it seemed like the right thing to do, and the author tells us he made a conscious choice to put himself in a position to do it. The other man is arrested, and Fairless goes home with his wife. If this were just an anecdote of an isolated incident, it might have just rested where it lay. But, as Fairless shows us over the course of the book, there are far deeper implications of his actions, and his feeling that he had to act.

The personal access in Mad Blood Stirring is the core of the book, and the reader’s entry point to this exploration of violence. In the chapters to come, Fairless keeps an eye on his own experiences and emotions while going down the pit, level by level, to investigate the evolutionary and behavioural impulses that lead to male violence. A former journalist for the CBC, Fairless spends time with professional MMA fighters, a high-school football coach and his team in an impoverished area of Toronto, a criminal on the lam, a serial rapist, and a murderous psychopath locked up in a maximum security mental health centre in Penetanguishene, Ontario.

What the author learns from these interactions is relayed empathetically, but it is never finessed or glossed over. And, by looking directly at these violent men and actions, Fairless provides an unusual insight into a topic that most people rarely engage with in earnest.

I met with the author recently, in Toronto, to talk about the process of writing the book, and the personal journey behind Mad Blood Stirring.

*

Kevin Hardcastle: When you were younger, did you have an experience with violence, like fighting in the street, or those urges to intervene in physical altercations that you talk about later as an adult?

Daemon Fairless: I mean, when I was a kid I lived in a below-blue-collar neighbourhood, a really poor neighbourhood in Halifax. And I would fight with the kids across the street. And by fight, I mean they would initiate and I’d survive. In high school I think I would’ve done just about anything to avoid a fight. I was super sensitive at that point, and I didn’t grow until late in high school. But even when I grew I didn’t have it in my head to fight. All that stuff just intimidated me.

While reading the book I kept considering my own experiences with violence, and writing about it in fiction. Trying to understand how it manifests. When I was in high school I got into something like a blood feud with these other rural folks, that ended up in a series of fights where I could’ve been killed. That sort of cured me of those urges you talk about in the book. I realized early I could die behind this. And those people I was fighting didn’t give a damn.

You realized they’re way meaner than you were.

Absolutely. And when I got out of there, to Toronto and university, it was just over. Simply from being out of that environment.

Well, it’s like a form of gang violence. And it’s almost in its organic form, or whatever you would call it.

You know, I think about this a lot—that fighting is a tool, and if it works for you, it’s very hard not to use. It’s a way of resolving all this alpha-beta animalistic tension. I think we can all do the math on how a physical altercation is going to go; you sort of do it in your head. I might have an idea it is going to go a certain way from the jump. So, I’m not going to do all the stepping up and talking, escalating it. I’m just going to get right to it and exert my will. And so, it becomes a very quick tool. And I think that one thing that happens once you get the shit kicked out of you is that you say to yourself, “I can’t beat everyone up, so I’m not going to put myself in this position at all.”

That was certainly where I got to, after being on the receiving end.

If you get beat up in a non-lethal or traumatic way, it probably can help you stop playing that game. I was talking to someone the other day who went through the same thing [as you] in high school. As I mentioned, I never did. In many ways I was just a peaceful dude, until I wasn’t. When I did get in fights as an adult, I was a lot bigger, and I was extremely lucky. I’ve rolled sevens every time.

I liked that you know that, and say so in the book. Also, as you mention in the early pages, you have size. That can go both ways, for sure. But now as an adult with size, and training and some skill, you know you have a good shot to come out of a fight okay.

Yeah, eighty-five percent of the time. Or you get killed. I try to tell myself, “The next fight is when I die.”

That’s what being older and my experience with training in Muay Thai and boxing taught me. When you get on the tough-guy ladder you realize you are nowhere compared to real dangerous people. There are levels of violence so far beyond you.

And that’s why I think about evolutionary and psychological factors, because we are emotionally tuned to think, “If I’m the biggest and meanest, I’ll win.” But then there are guns and knives. Or, in my experience, I might get so focused on one guy, the main person I’ve been in a confrontation with, that I forget about that other guy coming from my blindside. You can get hijacked by these notions.

I try to avoid all of that now. I make a conscious effort. I try to dress a little nicer. I’m not even going to present as a tough guy. I’m gonna look like a dad.

But if you were in the same mindset of hyperawareness that you need for a fight, or a combat zone, you can’t take that if it’s your whole life, every minute of every day.

And that’s where I’m at now, with accepting a level of vulnerability. I’ve got to be cooler headed, not looking for the danger always. Essentially all of the instances of violence I’ve been in [have been] as a result of me being hyper-aware, because I think, at some level, I’m anxious. As we talk about the inherence of aggression, many think that just means people are mean and nasty, but there is a lot more to it.

What I’m saying is that, at a basal level, most of the guys I’ve met—with those one-in-a-hundred exceptions of course—most of us at some level are operating at a certain level of anxiety. I’m not saying we’re timorous little creatures, but that hyperawareness, that hypervigilance, is part and parcel of that inherent state we’re talking about. We pay attention to our environment, to each other’s body signals—sexually, in terms of aggression, in all sorts of different ways. We’ve got all these signals going on all the time. It took me a long time to realize, or at least admit to myself, that the aggression that comes from being in this mindset is a response, a fairly inherent response, to an equally inherent anxiety.

People call it status anxiety, pack-hierarchy anxiety. I’m fine with that. So now, given that I’m aware this anxiety exists, I don’t have to be on that hyper-alert level, because it takes hold of you. I want to be a creative, constructive guy. And do you know how much time and thought it takes to be like that, anxious and hyper-aware all the time? It takes over everything.

I’ve tried to explain to friends of mine in the United States that Canada actually has a significant history and culture of aggression, violence, and even organized crime. From the major crime to the petty, this underbelly of Canadian life seems to be ignored all too often. We are not nice in many ways. We are not nice people.

And in many ways the whole “sorry” thing is about a pre-emptive defusing of conflict. All the sorrys are just trying to stop something from escalating. It’s a pre-emptive strike to defuse a situation. That’s what that niceness often is, and underlying it is that dangerous anxiety that can lead men to violence.

In our popular national literature, few of us want to talk about violence nakedly, or look at it head-on. As a result, authors and readers may begin to think all violence is the same.

I think [people get] confused because they’re not facing it head-on. I had this really interesting experience, with an acquaintance of mine who is gay and was in an abusive relationship. This acquaintance was a psychiatrist, so I was kind of like, “What can I tell him?” But we had this conversation and the conversation basically came down to, “Your partner is using these ancient rules of confrontation and aggression to control you, and you’re using these lovely rules of civilized rationalism to try to win that conflict. So that will not work.” You only resolve the situation but understanding the rules that the other violent person is playing by.

And that doesn’t mean anyone is saying understanding them is accepting them as good.

The thing is that when you’ve realized this imbalance, and realize it’s probably not going to change or be resolved in a peaceful way, then you can make the decision to try to just get out of the situation. Which I think he did.

Also, at that time I was training jiu-jitsu, about five days a week, so I took him to a jiu-jitsu class because he was interested, and for him I think it was like probably the emotional equivalent of taking an uninitiated person into a serious BDSM situation. He didn’t react well. It was just too much.

We really get freaked out about the emotional intensity of something like grappling. Even just the basics, they can so overwhelm people with the intimacy and physical closeness of it that they can’t see it as sport. All these real fight emotions just start firing off, and they can’t see past that yet. But, the thing I found in training, when you get used to it, is that you can kind of just bring your emotions under control. And then you start to solve it physically, and it’s no longer a big deal.

But the thing that I found most interesting was that this guy who worked as a psychiatrist was encountering this area of human behaviour that was just overwhelming to him. And, I mean, this is a guy who deals with all sorts of horribleness in his job. In that way, I really started to consider that we are the same way about this stuff that the Victorians were about sex. I mean, on TV or in entertainment, we want the violence, we’re asking for it—as long as it’s fictional or dramatized. As soon as you show them violence honestly and tell them, “This is what’s really happening,” they say, “Whoa. No, don’t show me that.”

I was at Canada Reads this year, and watching the second day of debate. And I found the direction of that debate really frustrating. Two of the books especially, The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline and American War by Omar El Akkad, kept banging up against this unbelievable resistance to accept and explore the realities of violence, war, cultural genocide, colonialism, and the potential of catastrophe from climate change. Their defenders, Jully Black and Tahmoh Penikett, had such an uphill battle trying to get across exactly how important it is for Canadians to look at all of this head on. But the resistance to those ideas, and the reckless sort of arrogance shown in dismissing those books, without engagement, really highlighted that inability or ignorance to address the ugly, difficult parts of human behaviour.

They just couldn’t see it as something that they should have to look at. “Alienating” was the word that kept coming up. With The Marrow Thieves especially.

We’ve created such a nice, civil society for ourselves that people can now be like, “I’m not going to get my kid immunized.” I mean, I lived in India, and no one there says that because they know their kid may well die if you don’t get them immunized. But here, because everyone has been in a more advantageous position for things like vaccines, you’ve got this barrier of safety around us. No one thinks that mumps or polio is real. It’s an abstract thing that only a certain type of people get.

And I think it’s the same with violence. People think, “Well, that won’t happen to me.” Really? That’s stunning.

What I saw that day on Canada Reads was a sort of desperation to be forgiven, and see something resolved. And what I liked about your book is that you don’t do that. Many of these violent men can’t be resolved. There’s not even resolution in your accounts of your own personal journey, and struggle with violent behaviour.

One of the things that a lot of people have written or said about the book is that it’s “terrifying.” But what I’m writing about is what’s happening everywhere in the world. It’s under the surface, even as we’re sitting in this restaurant right now. Again, to get back to that Victorian approach to sex analogy, we’re blind. We’re willfully blind to this. Though, it’s not like I’m saying we should revel [in] it.

We say we want a more civilized society, but I don’t see how that happens unless we face these things. I’m not suggesting some kind of social movement, but for me, I have changed myself as a result of writing this book. Just from facing the stupidity of some of the actions, and the instinct behind them. So, when people say what I’ve written is “terrifying,” I’m a little dumbfounded that they aren’t putting it together that you could get the same kind of story from the news every day. There’s nothing new about it.

But we have this amazing ability to cordon off that reality for some reason. And I mean, part of the reason I left the CBC is because I found reporting on the news frustrating, because as much as we’re ostensibly reporting on reality, what we’re doing is we’re sanctioning certain stories, certain types of stories to tell ourselves, and the underlying story that we’re telling ourselves—the meta-story—is that if you follow the rules and you do your job and all of that, bad things probably won’t happen. And it’s just kind of a pat explanation of the world, right?

All of this seems patently clear to me, whether I’m articulating it properly or not. And, I’m not an especially violent guy, but we live in an especially violent world, so I guess I’m a little stunned and think, “What world are people living in, where they’re not aware of this?”

Were you worried the honesty in the book would just switch people off?

You know, I guess my bigger concern was writing a good book. My overwhelming anxiety writing this was more, “Can I do it?” I’m not too concerned about whether or not people can handle the content, but I do find it interesting that, like, a Jo Nesbo can write the goriest details for their thrillers and people are like, “That’s great.” Yet, if you write a reality-based book about violence, people think there is something weird and terrible going on. Well, the weird and terrible thing is actually not wanting to face it.

What I liked about your approach is that the book accepts and investigates negative aspects of male violence, but still judges it and weighs it out honestly. And makes you look right at it. Nothing is ever explained away. I think this subjective element really works. Especially in parts where you interact with the rapist or killer, and share your distrust of them even while you’re trying to understand their behaviour.

I think I kind of uncoupled a lot of things that hold back journalists and hold back journalism. I realized I don’t really have to be a journalist while doing this, I can just be a guy who’s trying to figure these people and impulses out on a human level. And that worked a lot better. It really became a lot more freeing and it is also just the way I work. I don’t pretend to know everything, and I could totally be wrong about everything. And I’m okay with that. Show me good evidence to the contrary and we could talk about it. I’m cool with being wrong and knowing that there’s stuff I’m wrong about. There’s bound to be something off the mark when you write a three-hundred-and-something-page book on something as complicated as this.

But at least it starts the conversation.

I think as long as you fool yourself into thinking you can look at all of this objectively, you’ll never understand it. I’m willing to be co-opted by my subject, and I think that’s the whole thing about violence. When it starts to get hold of you and it starts to distort you—because it distorts your perception, and that’s why I’ve gotten in every fight. The emotions start to distort your rationality.

You convince yourself, “I should be doing this.”

Yeah, “This is the right thing to do. This is only thing to do.” And until you’re willing to be co-opted by that experience, you don’t understand. It can remain this abstract idea that you get frustrated with because people aren’t behaving rationally. You cannot understand it until, like you said, you put a toe in, and that’s all I’ve got, my baby toe in. But it’s so gripping that you still have to delve deeper to understand. So, I think we’ve got all these well-intentioned policies and thoughts and programs to try to deal with violence. But as long as people delude themselves, or deny the importance of the subjective experience of violence, they will never be able to control it.

I had arguments with people who’d read the book early on, regarding some of the guys I wrote about, like Nelson, the fighter. After reading an early draft, people were saying, “You’re being too nice to (the subjects).” And I was trying to explain that the people I’m writing about are doing what they’re doing because they’re going through something in their life, and training in martial arts or combat sports is helping them as people. Going through training or being around it like I have lets you gain an understanding of how it affects you. So, having people with real, subjective experience with the emotions that come about in combat sports, I think these are the people who, if they’re analytical and compassionate, are better suited to control those emotions. I have very little faith in people who’ve never been in a violent altercation, who’ve never experienced these feelings, to address them. If you’re telling me to control these things that override rationalism with rationalism, you’re an infant in terms of your understanding of those emotions.

So, because there’s this sometimes understandable disdain for fighters, we’ll have a tendency to ignore their insights into these emotions, and we end up losing the ability to learn from that subjective knowledge.

Similarly, in literature, there’s a tendency to ignore the voices of people with varying subjective experiences with violence. I was on a panel with David Chariandy, the award-winning author of the book Brother, and the poet Matthew Dickman, where we talked at length over the fact that people have criticized certain writing about poor people, or violence, and have been confused by it, because they can’t see past the abject representation of it. People seemed to want the protagonist’s mother in Chariandy’s novel, for example, to be more abjectly miserable in her circumstances. That’s not the way it always is. Dickman also talked at length about how violence doesn’t happen the way people want to believe.

There’s no drama like people think there is. It’s a thing that happens and you deal with the consequences.

That’s why I’m happy to see these writers get their stories out. Especially in contrast to this environment of academics and “public intellectuals” who are assigning their versions of masculinity with an agenda and without this level of experience, I think we’d see less of that swing between a fear of masculinity and this desperate defense of it.

It’s funny, because I think one of the classifications of this book is gender studies, and I didn’t sign up to write about masculinity. I mean, violent men are definitely in the broader discussion about masculinity, but I didn’t spend a ton of time thinking about manliness or maleness or any of it, I just wanted to look at the way the world is. I wanted to look at real people doing real things and find out what’s going on there. It’s really that simple.

I feel like I’m interested in the same subject that people are interested in, when it comes to violence, but I speak a different language. And for me that language I’m speaking is the easiest way to articulate this subject, and what is really happening. There’s lot of the work in sociology that covers social factors that lead to violence. I believe that, I don’t disagree at all. You can be schooled or conditioned to be performatively masculine or whatever you want to call it. But I don’t know if talking about it that way helps the guys who are doing it actually think about it.

I think you’re right. Because it’s undeniable. I mean, you were very forthcoming about your urges and feelings, or in the section of the book where you detail graphically violent, disturbing hypnagogic images you would have before sleep. For me, I think about those people who tried to kick my head in every day, and that was decades ago now. I think about fighting them again, differently. About revenge. That’s been in there since I was seventeen.

Again, that’s where I think some evolution comes in. I mean, your experience in your small town is sort of a great analogy for the way parts of society have always been: you’re in a tribe and if you are taken out of that tribe you’ll probably die. So you try to prove something. Also, you’re finding your place in that hierarchy of a small town and if you end up in a bad place within it, the consequences can affect you for the rest of your life. It’s not surprising that you still think about being physically attacked and overwhelmed by other people. I think we’re keyed in to take it very seriously. Because it conditions you to think that, if you aren’t the guy who is going to change that situation, you’re going to be the guy who’s getting beaten down.

So, obviously we can say, “I don’t live in that world. Those are silly thoughts.” Well, they’re not silly. They’re real.

They’re formative, too.

Yes, they’re formative and they affect how you behave. I don’t know about you, but my ambition to be a good writer is kind of a healthy way of taking that anxiety and status concern and processing it in a more productive way.

But you have to accept these feelings as they are before processing them.

Yes. Because if we don’t acknowledge these emotions, we won’t know what the cause of related anxieties and impulses are. And you’ll try to cope with it however you can.

Because of what we’re talking about, and my own experience writing about violence, I worried about your book being just dismissed as a book for men about violence. But, of course, male violence really is a feminist and women’s issue to a large extent—there’s even a quote to that effect on the book’s jacket.

I see more reviews about this book and hear more about the book from women than I do from men. And, in fact, in writing it, almost all of my readers were women. I was trying to make sure I was triangulating the direction of it based on their responses. Women so far have been really supportive of what I’ve written about. It was interesting to me that Jane Doe, on the back cover, calls the writing feminist. I’m great with that, but I just tried to outline real things that I saw, and because the book does that, she sees it as feminist because it deals with many of the issues that feminists are concerned with in violent men.

It also doesn’t let anyone off the hook, as we’ve discussed. It goes against some idea that because you’re talking about male violence that you’re letting the fire breathe.

Or by saying that just because there’s some inherent reality to the emotions behind violence that it’s okay. No way. There’s inherence to alcoholism, but we can still know that it’s bad.

That’s why investigating all these variations of violence is useful. Without that, we’re not going to know what is salvageable. I think of Romeo Dallaire’s writing on boy soldiers, who are made violent, and some warlords, whom he considered inhuman, more like the killer in your book.

I think we make such strong, understandable condemnations of people who have been violent, that we tend to do this “othering” with violent people, just as some do with their victims. They’re now “that type of guy.” When you do that, you basically throw away the child soldiers in the sense that they’ve also done terrible things. We need to get to an understanding that this kind of violent behaviour can be elicited in most of us, and that much of it is also correctable. There’s a way of being more. I’m not suggesting we go hug a rapist, but if you really want to understand and change people this is necessary. I think everyone in the book, other than the psychopath, didn’t need to be violent, they weren’t innately violent.

When you investigate these differences without saying that violence is one monolithic thing, you see where you could actually try to prevent or handle some of it. We’re doing that now. Trying to stop normalizing violent behaviour.

Again, we’re not saying give these people a hug and not deal with them. I mean, the rapist in the book is the first to admit this. He actually called me a few weeks ago, after he heard my interview on CTV, and he said, “I thought you spoke about me respectfully, and you still didn’t let me get away with anything. You weren’t suggesting it’s okay that I did what I did. But you still treated me like a human.”

Glenn Robitaille from the Penetang mental health centre kept telling me over and over again—kept hammering in, and he’s not a guy to try to hammer something home, he’s a very chill guy—[and] one thing he kept talking about is the relationship between shame and doing really shitty things. You should be ashamed if you killed or raped someone, one hundred percent. But in many of these cases with violent men, they feel shitty about themselves to start with, because they might have suffered abuse or violence in their own life, and it becomes a kind of cycle. That is one of the more complicated issues in dealing with these men. It makes sense to shame and have people feel bad about the things they’ve done. But if they don’t have a way out of that shame they keep going deeper down the rabbit hole.

Because it’s either that or die.

Sure, but also, say you have some horrible thoughts in your head, in one form or another. If you tell yourself, “I’m a piece of shit. I’m garbage. I’m a monster,” and you can’t be open about your feelings, then, when these thoughts come back, you might go, “Well, I’m a monster. I’m going to go with that.” As opposed to realizing that these are normal issues that most people have, and you have a choice to act on these emotions and instincts. And, even if you’ve chosen to act on them once, you can choose not to later on in your life.

It’s like, when you’re in the gym and you’re like, “I can’t lift this”—do you come back another day and make yourself better, or are you just too weak to lift it? If you choose to be weak, you’ll be weak. I hate to use that gym analogy, but there’s something to it.

It’s that misconception again that violence comes from a place of strength, but really where it comes from, as I think you’re saying in the book, and what I agree with, is from a place of fear and weakness.

It almost always comes from place of fear and weakness and we co-opt that as a form of strength, but it is a shitty form of strength. It’s a really destructive and shitty form of strength.