In an obsessively interconnected world in which everyone everywhere is encouraged to share everything all at once, our attention spans grow threadbare, and signals are increasingly drowned out by noise. It’s natural, then, that we should be drawn to the stories of those for whom communication itself is a nightmare. Naoki Higashida’s book The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism is ostensibly a handbook on how to understand young people with the Japanese teenager’s disorder, but Higashida’s pleas for empathy and time—“We really badly want you to understand what’s going on inside our hearts and minds”—are resonating with “neurotypicals” too.

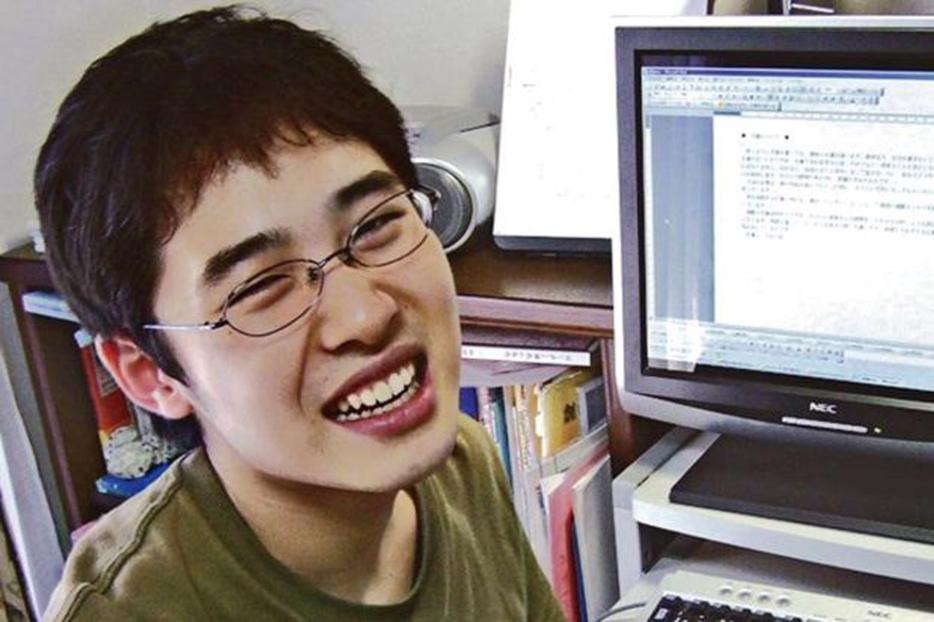

Higashida, a native of Kimitsu, near Tokyo, wrote The Reason I Jump in 2007. Its English translation, by novelist David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet) and his wife, Keiko Yoshida, appears at a time when fiction about teenage boys who seem to be on the American Psychiatric Association’s “autism spectrum”—typified by “problems with thinking, feeling, language, and the ability to relate to others”—is growing in popularity. From Mitchell’s native UK alone have emerged Iain Banks’s last novel, The Quarry (published in June), Gavin Extence’s debut, The Universe Versus Alex Woods (published in May in the UK, in June in North America), and the wildly successful theatrical version of Mark Haddon’s 2003 novel The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, which debuted last year. And The Reason I Jump has been a bestseller in Britain since its publication in July.

Higashida’s book intersperses Q&A’s about autism (e.g., “Why can’t you have a proper conversation?”, “Do you prefer to be on your own?”) with fiction, and his short stories bolster his more straightforward explanations. His writing, as translated by Mitchell and Yoshida, is clear and unpretentious, but also evocative. In reply to the question, “Why do you get lost so often?”, he explains how “people with autism never, ever feel at ease, wherever we are. … I don’t think we’ll ever be able to reach our Shangri-La … I know it exists only in the depths of the forest or at the bottom of the deep blue sea.” Clearly, not everyone with autism is as literal-minded as Curious Incident’s metaphor-averse hero, Christopher Boone. Higashida closes his book with the story “I’m Right Here,” in which a boy dies and returns as a ghost who can’t be seen or heard by his parents, despite his attempts to comfort them. Higashida explains he has written the piece “in the hope that it will help you to understand how painful it is when you can’t express yourself to the people you love.”

Mitchell and Yoshida came across Higashida’s bookwhile casting about for literature to help them with their own son, who has autism; in his introduction, the novelist calls it “a revelatory godsend.” Over the phone from his home in Ireland, Mitchell says Higashida’s often figurative writing “challenges received wisdom,” which perpetuates “the idea that autism is about being a savant, being able to memorize phone books and π to the 100,000th decimal place.” Indeed, Higashida comes across as warm, endearing, and in some ways heroic. Because of his difficulty speaking and writing, he composed the book by pointing laboriously to letters on a Japanese alphabet grid. He often mentions the difficulty he and others with autism have in making themselves understood by neurotypicals: “The truth is, we’d love to be with other people. But because things never, ever go right, we end up getting used to being alone.”

In his introduction, Mitchell offers a “thought-experiment” to represent what goes on in the mind of someone with autism: it resembles sensory overload. “A dam-burst of ideas, memories, impulses and thoughts is cascading over you, unstoppably.” Where neurotypicals have internal “editors” that filter things out, “people with autism must spend their lives learning how to simulate” their functions. Higashida’s fictional counterparts, like Haddon’s narrator, Christopher, are constantly trying to cope with the overwhelming, intrusive nature of people around them, well meaning or otherwise; they have to figure out how to interact with others by deduction rather than intuition.

In Curious Incident, Christopher considers himself a detective, attempting to discover who killed a neighbour’s dog, but also how to interpret other people’s emotions and desires from visual cues he’s not attuned to picking up. There’s something of him in The Quarry’s 18-year-old Kit, who refers to himself as “very clever, if … weird, strange, odd, socially disabled, forever looking at things from an unusual angle.” Similarly, Extence’s Alex Woods has a remarkable gift for astronomy but often has trouble relating to people: “some said,” he reflects, “that I didn’t even feel emotions in the same sense that regular people with regular brains did.” He’d rather read Kurt Vonnegut than make friends at his school.

Higashida often mentions the difficulty he and others with autism have in making themselves understood by neurotypicals: “The truth is, we’d love to be with other people. But because things never, ever go right, we end up getting used to being alone.”

Granted, none of these characters is ever explicitly identified as autistic in the books, or as having Asperger syndrome (considered by the American Psychiatric Association to be part of the autism spectrum). Alex Woods’ condition appears to derive not from genetic or environmental factors, but from being struck on the head by a falling meteorite. Haddon has said he doesn’t want to “exclude people” by defining his sympathetic narrator’s condition in any way, but he has admitted that if Christopher were diagnosed, he would be said to have Asperger’s—a manifestation of autism where language and cognitive development are not delayed. Central to all of these books is that fact that for their protagonists, the Forsterian motto “Only connect” is a near-impossibility. But it’s not for lack of trying, or for an impoverished inner life.

In his survey “Autism Fiction: The Mirror of an Internet Decade,” philosopher Ian Hacking identifies a theme in contemporary literature of “the nerd as autist and the autist as nerd,” brought about by the internet’s creation of “a communicative life other than the ancient neurotypical one.” Via text and email communication, “No longer do I look at you, make eye contact, or notice bodily discomfort, when we are talking to each other. … We form social groups of people who would not even want to set eyes on each other.” For Hacking, neurotypicals and those with autism are starting to resemble one another.

But Mitchell emphasizes the differences: although he praises the fact that “information-age communication allows people who do have autism to communicate more like the rest of us,” he notes that nuances can remain barriers for those with autism. “You get a high level of expression in emails; it gives us all practice in becoming better writers,” he says. “I think we communicate more, and in a fine-tuned political manner which would remain very severe challenges to people who have autism.”

The experience of a narrator with symptoms of autism could be viewed by neurotypical readers as an analogue for their own—how they’re confronted with too many demands on their time, too many screens and messages jostling for their attention, their inner “editors” increasingly unable to cope. The caveat remains that stories such as Christopher’s are fiction, and moreover, Mitchell is keen to distinguish between people with Asperger syndrome and those with a more severe form of autism. “Asperger’s is a gift to novelists” in creating characters, he says. “You get a highly articulate individual whose very difficulties with relationships and the processing of emotions allow a fiction writer to bring to the surface these issues that a novel is naturally interested in.” Indeed, young-adult males have made useful outsider figures for authors determined to expose the follies of their worlds, from Hamlet through Catcher in the Rye. What with the rise in diagnosis (autism is now identified in 1 out of 50 schoolchildren in the U.S., and mainly in boys), the archetypal 21st-century outsider may turn out to be the teenager with autism.

Higashida muses that his disorder has “somehow arisen out of … the selfish planet-wrecking that humanity has committed.” People with autism, he writes, are “like travelers from the distant, distant past” who would like to “help the people of the world remember what truly matters for the Earth.”

For Mitchell, autism itself is better understood as “autisms,” and “the idea of a spectrum is something of a conditioning straitjacket. It just gives you one dimension from mildness to severity, whereas I view it more as a 4D cube—mildness, severity, literalism to symbolism, and fluctuating in time, both in the course of a single day and within the course of a lifetime. Many of the autisms in the world would almost preclude a novelistic narrator because there are output problems: How do you write a novel where your protagonist cannot communicate? Which is in some ways like having a non-visual picture, or music you can’t hear, if you’re a composer.”

Nonetheless, Mitchell recently wrote a short piece whose young narrator has a rather severe form of autism: “Lots of Bits of Star,” which will appear as a print in a box-set of fine art prints, coinciding with the launch of an exhibition this fall in L.A. by Kai and Sunny, the illustrators of The Reason I Jump. The prose is dense and seems to go off in many directions at once, and yet its voice is fresh and exciting: the writing feels cubist. The piece, Mitchell says, “feels like a stem cell that could grow into a larger body. I would like to see if I can learn and show more about autism by having a narrator who is autistic as opposed to a highly articulate ‘Aspie,’ as they call themselves.”

Perhaps it’s fitting that “Lots of Bits of Star” should take a while to decipher. For Higashida, patience is perhaps chief among the virtues; certainly it’s necessary in raising a child who has autism. To be such a parent, says Mitchell, “you have to become a stronger, kinder, more compassionate, more patient, tougher, clear-sighted person. … It’s an expensive course, but this is the gift that autism brings: practical, day-to-day, gritty, expensively bought but nonetheless real enlightenment about the human condition and the human heart.”

Higashida muses that his disorder has “somehow arisen out of … the selfish planet-wrecking that humanity has committed.” People with autism, he writes, are “like travelers from the distant, distant past” who would like to “help the people of the world remember what truly matters for the Earth.” And while Mitchell admits this image is “one or two degrees more mystical than I am generally happy to venture,” he’s captivated by Higashida’s drive to use his communicative faculty—a “lucky card” he has drawn within the pack of autism—to help everyone with the disorder “explain what’s going on in their heads.” In translating the book, he and Yoshida are simply looking to help further. “It’s really different when it’s not about you—when it’s about something bigger,” he says. “If [The Reason I Jump] outsells everything else I’ve ever done put together, then I’ll be the happiest writer of all.”