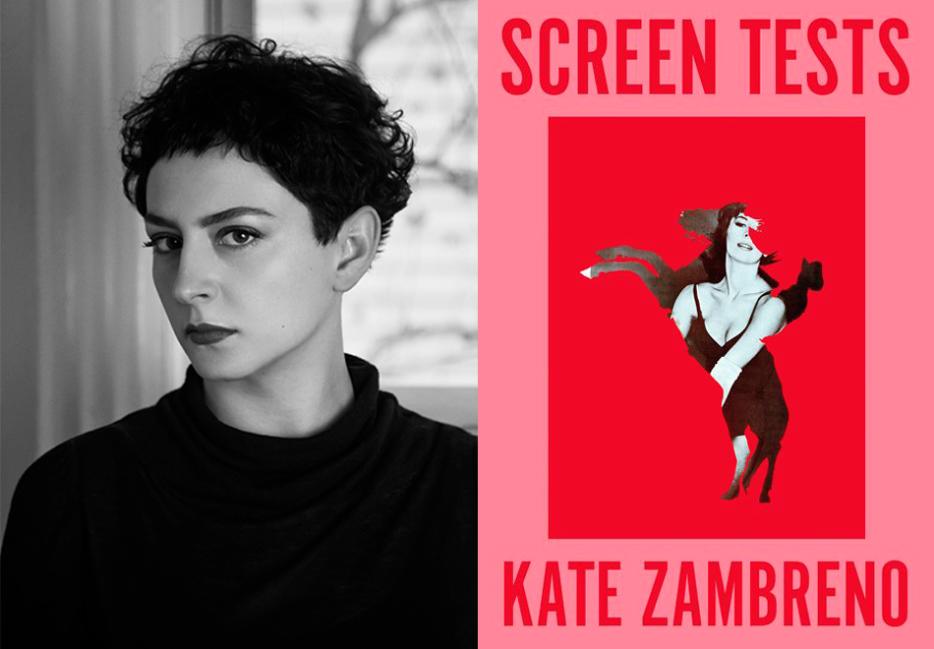

Kate Zambreno is drawn to the ambulatory nature of the photographer and writer Moyra Davey’s work, how she uses texts to roam through an idea. A film by Davey features her pacing—a visual metaphor for the monologue she's speaking—through her apartment, talking evenly into a microphone that picks up the gulps of air she takes before her next sentence. I picture Zambreno, the author of books including Heroines, Appendix Project, and most recently, Screen Tests (HarperCollins), as she works, physically moving in the same way Davey does, roaming through genre, time periods, and mediums. Zambreno works within the same interdisciplinary nature that once caused Anne Carson to be accused of naïvety.

We can hear Davey speak in the film, but she’s not necessarily speaking to us. It feels like she’s making a voice note for her own reference—layering the life of Mary Wollenscraft with that of her own and her sisters, the timeline overlapping like tracing the contours of a drawing with vellum.

Who is Zambreno speaking to? In Screen Tests, short texts are removed from the reader, allowing them to process each sentence in private. This distance begets texts that feel more personal than Appendix Project. The second half of Screen Tests is saved for essays—or rather, fragments linked together to form an essay, further proving Zambreno’s knack for lack of specificity. In both books, Zambreno gives the reader insight into the ambulatory nature of her process, a generosity atypical of writers.

The following interview provides further insight into Zambreno’s nesting doll mind, motherhood, bad reviews, and the nature of performance.

Tatum Dooley: In Appendix Project, you're using French philosophy and children's books as a lens to view your life in a way that it becomes an autobiography.

Kate Zambreno: I’ve been thinking about not how to fill a text with myself, but how to empty myself from a text. Recent work, since Heroines, has been characterized by an ambivalence towards the first person. A lot of the specificity is emptied out of Appendix Project but it penetrates through almost unknowingly.

The children's book stuff is my favourite part of Appendix Project. I think my meditation on the strangeness of these children's books is about how these appendices, these lectures, were written in pure exhaustion. There's this pure ghostly state of exhaustion. Exhaustion is so much like grief and grief is an exhaustion where everything is slowed down and so you notice the strangeness of everyday life.

I read each talk in Appendix Project as a mind map. A single talk connected William Mumler to Roland Barthes to your own photo albums to the film Wanda to Goodnight Moon. How do you make those connections?

I think that's definitely what I intended with the talks, for them to be about the connections the mind makes and about finding surprising connections between things. The truth is I just read the same things over and over again. Bhanu Kapil's work is so much in Appendix Project because I teach her work and I read her work over and over again. I feel like Roland Barthes is throughout everything. Appendix Project is my failure and my attempt to write about the last couple of years of Roland Barthes's life. I'm really interested in the sort of ambulatory, or the idea of, like, walking in an essay. I think about the writer and photographer Moyra Davey a lot. She'll take on a subject for a book, like the notebooks of Jean Genet, but then she'll drift through all of her reading and put everything in connection to each other. For each of the talks I had about five or six objects that I was thinking through. I allowed for some accident and randomness.

You've mentioned that you had writer’s block after you published Heroines until your daughter was born. Was that a symptom of something larger? Do you have an idea of what brought on the writing block?

I was used to writing books that had very little readership except a small community. Heroines broke through and it kind of astonished me. It surprised me and I think it estranged me from myself. Some people had very, very, very strong reactions to Heroines when it came out. I found that paralyzing. Then I moved to New York. I felt very much closer to New York publishing which is closer to thinking of writing as a commodity. People began to ask me what my next book was and wanted it to be something as buzzy and as loud as Heroines was. I found myself withdrawing and wanting to go more into a private space which is the space of writing. I had to almost revolt against what New York wanted of me and what publishing wanted of me. What came out of that was a rich period of writing. I thought I had writer's block but really it was that I chose to think and read for a while. As soon as I gave birth, I stopped feeling writer's block. The demands of my life meant I had to take on more commissions and I had to be a little less precious about being paralyzed. I had to have a little bit more confidence.

I've noticed in Appendix Project and Screen Tests that you keep returning to the origins of things, the town you are born and also motherhood.

Book of Mutter only cracked the surface of me trying to write my origins. I feel like that's something that writers are uncomfortable about, it has a lot of shame associated to it. Those tend to be some of the most interesting areas to write, but they can take a long time. One of the areas my work has started to think about is childhood. I haven't really wanted to write [about] childhood or origins and since I don't really want to write it, the work kind of has a bruise under the narrative. I was surprised to find, in Screen Tests, how much I write about my father.

In a recent Paris Review interview, you said, "With the talks and shorter appendixes I felt more liberated to try to think through a weird collage of concerns and ideas, a live-wire essaying. I allowed myself to exist in this space of unknowingness. Maybe it helped that I was not planning on publishing them as a book, until they became one. They were more ephemeral, they were refusing the monument.” I wonder, is this writing similar to what you're interested in with the artist On Kawara—is the text a performance that's ephemeral?

I think that there was a lot of desire not to have the talks printed. I thought that that would have been really wonderful for me to have resisted having them made into a book because I think that would have been truly a tribute to their mortality and the performance of them. There was a moment in the book where I write about the writer Sofia Samatar, our dialogue about our desire to write a book and distribute it in train stations without our names. How literature can have this energy of performance, which is a desire of mine.

The first talk is a meditation on the daily paintings of On Kawara. I was really interested in this idea of painting as ritual and painting as process and painting a date much like Roland Barthes writes a journal in his Mourning Diary. The paintings stand in for a life lived. What is art but time and transcending time? I have this quote I've been thinking about a lot lately, which was in one of my notebooks from three years ago. It's from an obit of a painter who is really a critic. I don't have his name. He never sold his paintings, but he kept on painting. This is what he said about why he started painting again: "Although my guess is that the art object is done with. I myself go on making paintings but this doesn't have much to do with making saleable physical objects, making them is more like philosophical investigation, art criticism, or yoga.” I think in some ways the appendices were art criticism, philosophical investigation, and yoga. And so, my desire for writing to have that process feel to it.

The last sentence in each of the short stories in Screen Test twists the knife in the same way Lydia Davis does—it almost becomes like a poem. There’s a cadence to the stories that is enunciated in the last line.

I feel like I'm a prose writer who will never be seen as a poet, but everything I write is a desire to be a poet. When I finished Heroines, which felt like this very maximal work in a way, all I wanted to do was write one sentence stories. I'm really drawn to short forms, to the fragment, to smallness. I'm a huge Lydia Davis fan and also of Diane Williams.

Anne Carson writes, in the Gender of Sound, which you write about, how she's been called naïve in her use of bringing together different time periods and sources. And I wonder if that's ever been an accusation lobbed at you.

Yeah. That passage is about the accusations that she's been naïve in the past for bringing in all different time periods and styles. There was a review last week that brought in Heroines as being incredibly naïve. So much of Appendix Project is a talk about talks—it’s very meta in terms of being aware that I'm often invited as a wild outsider who does this naïve form of scholarship that would be considered very criminal in the university and academia, which is why I don't have a full time job. The truth is I don't identify as a scholar. It’s hard for me to imagine Anne Carson being called naïve. Maggie Nelson has spoken about earlier reviews of her books where she's been called similar things. When Heroines came out, the writer Sheila Heti sent me a very tattered copy of a book called Manet and his Circle, which is about when Manet's paintings came out he was derided as completely naïve, as a plagiarist, as a copyist, and that his paintings were incredibly ugly. It's very hard for us to realize that because Manet is in museums and these works are so beautiful but they were seen as, like, not painting. The idea that in certain time periods if you do something that's considered naïve or ugly you're threatening.

You write that Anne Carson says she always has six books by her side when she's writing. I wonder if you do as well, and what are those six books?

Well, it just changes with every piece that I'm working on. I'm currently writing a book about Hervé Guibert's To The Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. I'm thinking through Guibert's Compassion Protocol. And then I have Moyra Davey’s Burn the Diaries and The Station Hill Blanchot Reader and I have Foucault's Birth of the Clinic and I have Anne Carson's Decreation. When people ask me if I'm reading, what I'm reading, I'm like, I'm just reading Hervé Guibert all over again in translation.

I’m thinking back to when you said you started writing when Leo was born. Alice Munro talked about starting to write when she had children, that there was an urgency to write and finish a story as her children napped. So did Raymond Carver. There’s an urgency to write to provide, but also time constraints.

Ninety-nine percent of the Screen Tests and Appendix Project were written when Leo napped. Some of the times I had childcare and some of the times I did not. I sat next to Diane Williams [at an event] and I spoke to her about that, I think she started writing when she had children too. One of the things I said to her is that when you're a mother you're a ghost, there’s a sense of you being in the dark and being quiet for the baby. This difficult thing happens, your identity is through another. There is almost a loss of the self that happens, especially at first. It's about the baby. For me, this extreme loss of self was also a form of decreation. I think that's why I really desired to write. Writing is a way into and out of existence. I often write when I'm feeling the most ghostly and I felt extremely ghostly right after I gave birth. There was a desire to write myself back into existence, to mark, like the On Kawara paintings, I am still alive.