Has there ever been a better time to read Victorian novels? Their volume, their sheer scope, and their often-serialized origins all make for stories meant to be engrossing and enjoyed over a long period. Take your time; you have nowhere else to be.

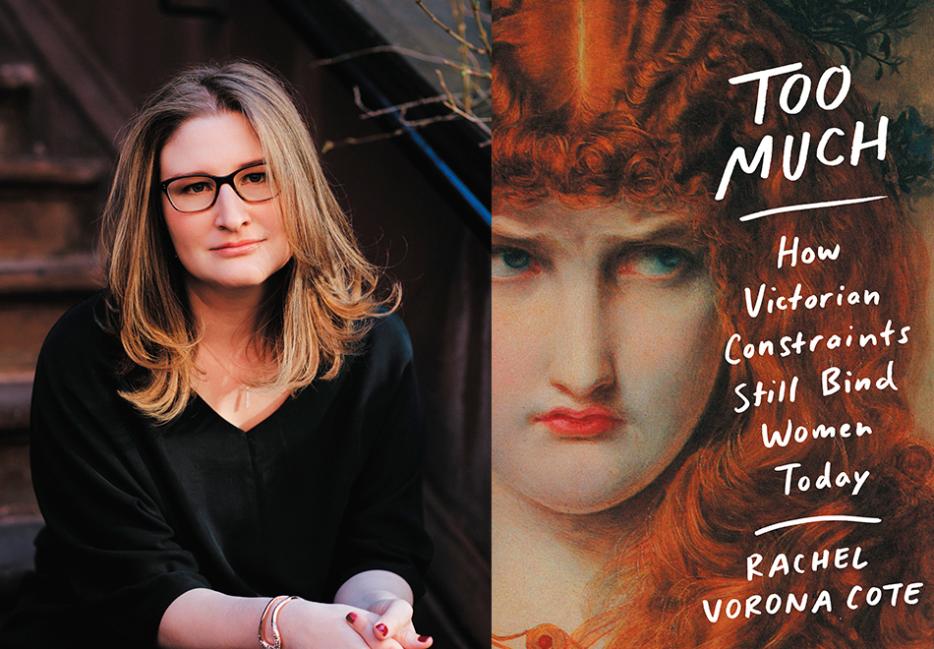

Rachel Vorona Cote knows her Victorians. With multiple degrees in literature, she applies her scholarly expertise to her modern obsessions in Too Much: How Victorian Constraints Still Bind Women Today (Grand Central Publishing). She traces a path from the Catherine Earnshaws and Dorothea Brookes of centuries past to contemporary characters, authors, and public figures, with a healthy dose of memoir tied in. The lessons that these books can teach us, Cote argues, are evergreen. The women who were maligned in the works of Charlotte Brontë and George Eliot for being too emotional, too unstable, too sexual, can serve as a conduit for how we understand how women are maligned still today. Cote and I spoke on the phone in early March, the day her book had been launched, as she was embarking on a multi-city tour that would, one week later, be postponed indefinitely.

Anna Fitzpatrick: Too Much is obviously rooted in the Victorian era, but you bring your subjects into the present, and cover a lot of literature over the twentieth century. Why did you decide to start with the Victorians?

Rachel Vorona Cote: There's a logistical reason, and then there's a conceptual one. The logistical side of it is that my academic training is in Victorian studies. The nineteenth century was a period in which there was that sort of really intense institutional scrutiny and stigmatizing of women and women's emotional expression that veered towards the extremes.

Sigmund Freud, he was a later Victorian. He came in at the tail end. You had a lot of white male doctors who were "treating" women who had maybe been sexually abused, or maybe had anxiety, really all sorts of afflictions, signs of distress. Rather than listening to them, rather than actually putting any importance on their testimony, their sense of what it meant to live in their own bodies, rather than listening to that, the catchall was hysteria. These women were hysterical because their wombs were running all over their bodies, whatever sort of nonsense medicine they were leaning into at the time. That was something that was quite prevalent.

It kind of makes sense, because the Victorian period was really a bananas time in terms of the way people were navigating issues of gender, issues of sexuality. The Victorians were really quite obsessed with sex even when they tried to pretend they were really moralistic about it. Women were then, as now, they were kind of seen as illegible in a lot of ways. And frightening. Especially as you got to the turn of the century and women started saying, "We want to work outside the home, we want to earn money, maybe we don't want to get married.” It dredged up a lot of anxiety.

What drew you specifically to the literature?

It's an interesting question because I've been reading it for as long as I can remember. When I was growing up, my mom started reading a lot of nineteenth century literature. She hadn't been a big reader when she was growing up, and then she started, I think she just wanted to fill in a bunch of gaps. She started reading Jane Austen, and she read the Brontes. I started reading these works alongside her. We'd watch film adaptations, like the BBC Pride and Prejudice, that was constant viewing in our household. In some ways it grew out of my relationship with my mom. I've always really appreciated the intensity. That sounds cliché, to say that considering the book I've written, but I think there was something very resonant for me in books that— [cuts out]

Are you there?

[a minute passes]

Are you there?

You cut out for a second.

I think I accidentally started making a call.

I do that all the time. When your cheek dials?

Ha. So, the Victorians. They're extremely dramatic.

Right.

And I can see how that would be really, really aggravating for people. When people tell me they really don't like Victorian literature, or they're put off by it, I completely understand that. It's very specific, even though different writers are doing their own thing. There is a sort of emotional urgency that runs throughout. I appreciate that. I especially appreciate that in the women who emerge in the text, especially in the books written by women, women like George Eliot and Charlotte Bronte. Women who were, to be clear, very problematic in a lot of ways but who were very frustrated with their milieu and who were responding to it in certain ways, ways that we would understand.

In the book, it seems that the things you love about this era and the things that really frustrate you are often very close together. I'm thinking of the chapter you have on Lucy Maud Montgomery, where you talk about how you didn't like Anne of Green Gables at first but you were very into Emily of New Moon. You wonder if Emily would have even liked Anne. I wonder how you felt about how so many of these women who are too much in their own ways, how they would interact with each other?

There are a couple of shows right now where I think a bunch of characters from different nineteenth century novels are sort of thrown together. There's Penny Dreadful, which I haven't watched because I can be kind of a weenie about violence and I heard it's gory, and then there's one I heard about that's based in Dickens, but I love the idea of putting all these different women together. A lot of them would probably hate each other. If you put Cathy Earnshaw from Wuthering Heights in a room with Jane Eyre, she'd probably punch Jane in the face. If she even gave her that much time. They would probably spar for a while, and then Catherine would get a little violent.

I think that it's really important to think about what sorts of characteristics or dispositions we regard as excessive, it's important to think about the sort of language that we use, and what causes us to regard certain people, certain practices, certain behaviours in this way, and to think about excessiveness as negative. The fact is, being excessive isn't necessarily positive. It can be true that a character like Catherine Earnshaw might be struggling under very patriarchal strictures. It can also be true that she's an asshole. She's not an especially kind or compassionate person, and she doesn't really think about other people. That's the most mild critique of her. She's a very compelling character, but I don't think anyone would make the mistake of calling her nice.

I think when you've got all of these strong personalities, it's not the case that they would mesh. It might be, because of who these people are and what they're willing to give of themselves, or it could be because it is very, very easy to internalize misogyny. If you're feeling anxious or you feel some solicitousness about aspects of yourself that you think maybe are off-putting, I know that this is something that I've fallen into where I might be inclined to critique that in somebody else and probably I'm doing that because it's something that I'm anxious about.

You talk about these Victorian constraints with fictional characters and real women in tandem with each other. How do these constraints apply themselves differently in reality?

Whenever we're talking about real people, stakes are inevitably going to be different. I can appreciate characters in Victorian novels who might be kind of jerks. Maybe take the good with the bad. But I'm not going to give myself that sort of pass, just because I always want to do better. I think when we're actually having a talk about real women and real women thinking about the way that we navigate our excesses or what we are told are excesses and how we navigate that conversation, we can absolutely talk about this with literature too, but I think it's just more urgent that we have to think about the ethics of it, too. I want for us to be able to extend more empathy towards each other, and I think that's definitely a guiding motivation for me in writing the book. I also think it's facile to say that being excessive is good, or “do whatever you want, you can't say anything to me because you're just stigmatizing me.” It's much more nuanced than that.

I think we have to think about, okay, what do we need to unlearn, what has made it difficult for us to live in the world, what sort of stigmas and ideologies have really shored up our subjugation, and the subjugation of people much more marginalized. Then there's also the question of, where's the boundary between that, and also thinking about how we have to navigate the world with other people. How do we honour ourselves and try to untangle ourselves from a whole lot of really nasty patriarchal and capitalist bullshit, for lack of a better term. How do we do that while holding ourselves accountable? Remembering that everybody is going to be living in the world in their own way. It's important to bear that in mind and remember that too, always. We can't think about ourselves as if we're inside of a vacuum. We're part of a web.

I can't quote it directly, although maybe that makes me less of a nerd, but I really love the novel Atonement by Ian McEwan. There's a really wonderful line or two, it comes in the section that's narrated by Briony, but the basic premise is everyone in the world is as real as you are. The thrust of that being that everybody's inner life, we're all walking around with all of these loud voices and all these competing emotions, and it can be very easy to forget that everybody is doing that too. Of course, there's the fact that it can be comforting and humbling, in its way, to remember that and to remember that other people are definitely not thinking about you, but also that most people are just grappling with themselves and trying to get through the day as best they can. I've always loved the way that that novel demands a sort of recognition of the fact that everyone has a really, really vivid interiority. If I were to try to suss out a moral code, that would be part of mine.

You identify as a woman who is Too Much, and you relate to a lot of Victorian heroines that way. Do you think it's possible for a woman to not be considered too much based on how you lay it out in the book?

First of all, it's very easy for me to find heroines to identify with, especially Victorian heroines. They're all white and cisgender, and so am I. I had a lot of access growing up. There is privilege in the amount of resonance I found in literature. I think that the notion of one being excessive, I think it is lobbed at a lot of people who aren't performing normativity in a way that social norms insist that we do. That said, I think that some people are capable of performing normativity according to hegemonic ideals. Some are more capable of doing that than others. Sometimes maybe it comes down to disposition. I think oftentimes it does come down to privilege. That's where I have to check myself, because yes, I absolutely felt very often in my life as if I'm spilling all over the place. I'm very emotional, and I have to navigate some mental illness and that can feel unwieldy, and there's this and that, but I nonetheless have a lot of privilege. There's a lot about me that in fact would not be considered too much. That would not be considered fundamentally excessive. I'm able bodied, I'm white, again I'm cisgender, I'm queer but I'm married to a man, so I have privilege there. I think this is such a good question because it really emphasizes the extent to which, and I don't know if this is maybe the way you intended it, but it does emphasize the extent to which—

[silence]

Are you there?

Are you still there? I don't know why my chin keeps doing that. I keep accidentally hitting mute. My chin is going all over the place.

You cut out about a minute ago.

Let me try to back track. What I was saying is, I think what is making me contend with and remember that however difficult it may be for me—or how difficult it may feel for me—to live in the world, to contend with the different sorts of expectations that still seem to prevail in terms of femininity, it is very much the case that it is going to be so much more difficult for so many other people. In America, people are just wholesale treated almost as excessive or extraneous if say, they need government support. If they're women of colour who need food stamps. That, according to the monsters running our government, well, that's too much. It's a continuum. That continuum is absolutely inextricable from white privilege and privileges of gender and orientation. That's been a really critical thing for me to keep in mind. I don't ever want to get drunk on the sense of my own subjugation. There are really pernicious trends and ideologies that I see as enduring, and it's distressing that there are so many continuities from the nineteenth century, but my book would be written a very different way by someone who was living a very different life from me.