The other night I had a dream I was on a mountain in the rain. This could mean one of two things: (a) I was remembering the time when I was on a mountain in the rain, in Banff, two years ago, or (2) I’m a pervert. A quick look at Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams confirmed the latter. Mountains, says Freud, represent genitals. So do ladies’ hats and umbrellas, theatre tickets, staircases, ladders, and footbridges. Of course, reading Freud as a means to self-diagnosis is as pointless as building Ikea furniture without the proper cartoon instructions. The conclusion is always the same: your dream means you want to have sex with someone you shouldn’t have sex with, possibly a parent. But it’s always better to spend 30 years in analysis to work out the specifics.

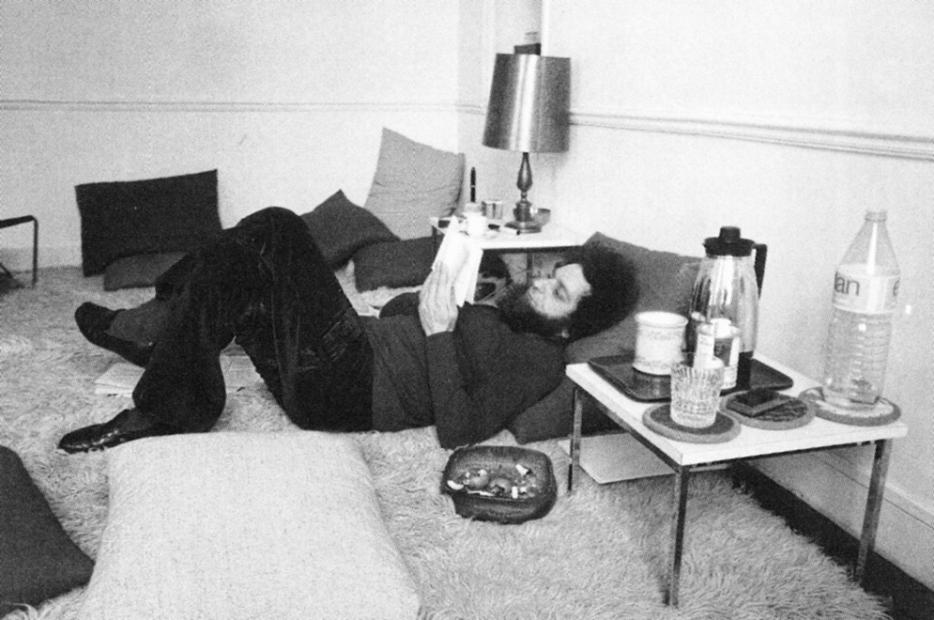

So what can we make of this dream, recorded by the late French experimental writer Georges Perec in May of 1970?

“The neighbor’s husband arrives,” he writes, in La Boutique Obscure, a dream diary just published in English, which I’ve been reading in bed the past few nights in advance of my own sick, wicked dreams of landscape and weather. “He is an old, tired man. He has no mustache. Or rather, he has one. He looks a bit like the actor Andre Julien, or maybe like Andre R., the father of one of my old classmates. In his hand is a case shaped like a large ballpoint pen, which is either full of many ballpoint pens or of one enormous pen with—let’s say—twelve colors. He nods, looks displeased.”

This one’s easy. Dimestore Freud can dispense with the enormous pen right off the bat: might as well have been a mountain or umbrella or a theatre ticket. And why twelve colours? Twelve apostles, maybe, or twelve tones in the Schoenberg system of musical composition, or twelve eggs, as in fertility, as in sex, as in having sex with someone he shouldn’t have sex with, possibly a parent. Or the actor Andre Julien. And so on. The trouble is, treating dreams as easy-to-solve sex-obsessed Junior Jumble puzzles shortchanges both the dream and the dreamer: they work so hard at their cryptic nonsense, why drive them to the same, tedious destination?

Perec never mentions Freud in La Boutique Obscure. He’s not interested in interpretation. He’s just writing down what happens when he sleeps. Then, over time, he detects a strange pattern: “I thought I was recording the dreams I was having,” he writes. “I have realized that it was not long before I began having dreams in order to write them.” In other words, the dreams themselves didn’t have to mean anything, sexual or otherwise, as long as they added up to some peculiar, unified project, in this case, the very book Georges Perec wound up writing.

Perec was known for creating literary puzzles and then solving them. His novel A Void is a 300-page narrative in which the letter “e,” the most commonly used letter in the alphabet, never appears (while we’re here, a special shout-out to the English, Spanish, German, Turkish, and Dutch translators who managed somehow to follow the same constraint). Why pick on the letter “e”? The literary journal Context figures the missing “e” represents the “e” in “mère” and “père,” or the missing parents in Perec’s own life. Both his mother and father were killed in the Second World War. It may also represent the “e”s in Georges Perec, the missing author of a work about private loss. Or, in the spirit of the Oulipo, the fraternity of experimental writers to which Perec belonged, it may simply be an arbitrary constraint meant to liberate the imagination from cliche. The particular constraint is irrelevant; the end result isn’t.

In the same way, the individual dreams of La Boutique Obscure are hopelessly opaque, but read 124 of them in a row and a dim picture emerges, either of Perec himself or of the dreamworld we find oddly familiar. I don’t have recurring dreams, but over time it seems like each dream I have is a chapter in some ongoing saga, with its own rules of logic and geometry and plastic time and space. For example, my dreamworld has no quarrel with paradox: I dream about my high school English teacher Mrs. Fillmore, only she’s also my sister. I don’t mean she turns into my sister, I mean she’s both at the same time. You’ve had this dream too. So has Perec: “He has no mustache. Or rather, he has one.” Freud is reductive. He takes each dream and dissects it, thereby killing it. But the dreamworld is a bigger, longer, more complex but also more consistent book: it unfolds over time, night after night, year after year. I may be troubled by some dreams but on the whole I’m not troubled by dreaming.

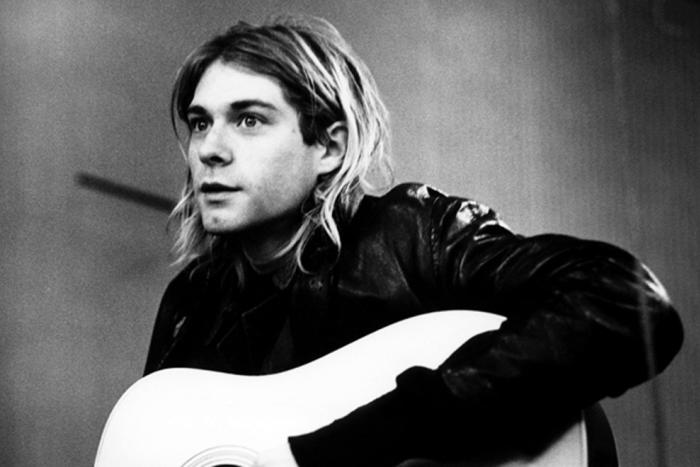

Graham Greene also kept a dream diary, which was published after his death in 1991 as A World Of My Own. As Malcolm Bradbury points out in his review for the New York Times, Greene believed in worlds beyond what he called “The Common World” of shared reality: he believed in the mysteries that exist “in the bathroom cupboard, in secret tunnels under the ground, in the labyrinthine world of espionage, in the realm of sexual deceit,” and in dreams. As a Catholic, albeit a Catholic troubled by the arbitrary constraints of the earthly church, he believed too in the world we’re not meant to see except through Revelation. The diary is a stealth autobiography of Greene’s life in the dreamworld. Again, the individual dreams (in one case he winds up on a riverboat with Henry James) might be thin stuff, but taken as a whole and over time a peculiar world emerges with its own logic and infrastructure and magic. It’s a world of his own, like Dorothy’s Oz. And he’s not making it up: this stuff actually happened, albeit in his head. In an odd way, both A World of My Own and Perec’s La Boutique Obscure are works of non-fiction.

“Now someone serves us food on a long table alongside our bed,” writes Perec, about a dream he had in December, 1970, “where two diners are already seated. They toss us a menu: appetizers, entree and dessert. I order only steak. They put in front of me a very strange dish, telling me it’s an appetizer, then that no, it’s a dessert for the diner at the end of the table. My steak arrives, it looks terrible.” Dreams may be nothing more than biochemical noise, the nightly neuronal discharge of static electricity, like touching a doorknob. Most of Perec’s dreams fit the noise theory: go Freudian all you want on the steak dream, it adds up to little more than the psychic remnants of a bad night at The Keg. But in page after page of banal weirdness, Perec is also daring us to think otherwise: that dreams may in fact be fragments of an ongoing story that will never end, as long as we keep revisiting and re-writing it every night.