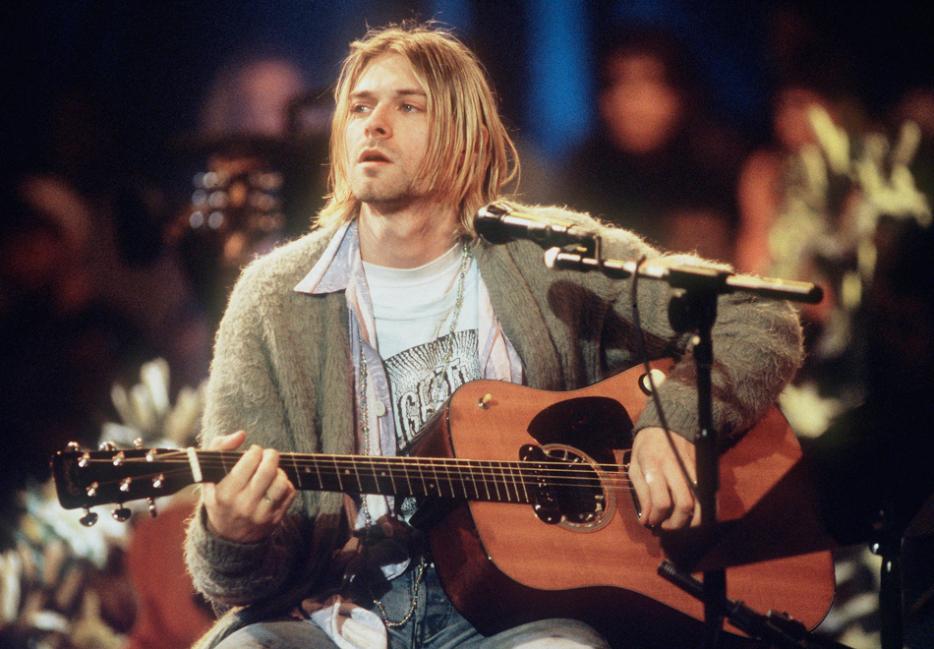

You’re going to write about the 20th anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s suicide. That’s a given. He was famous. He was alternative famous, i.e. blameless, and most of us saw him as a patron saint of our own conflicted feelings about wanting attention, endless attention. His suicide is also something that happened a round number of years ago, and, seriously, 25 years is just too long to wait. Who knows if the Internet will even exist in five years? As we speak, politically correct Twitter activists posturing about jokes are tearing it apart. Would a white man like Kurt Cobain even be able to succeed in today’s hostile online climate?

When we discuss Kurt Cobain, his death, his return, and the daily judgment of his widow that continues to this very second, take a moment to consider that question and remember: none of this is real. There are no human beings in this story—only archetypes, villains, and precious memories. One should think of the life and death of Kurt Cobain as one generally thinks of morality and/or the Internet: as a reality that fluctuates depending on the argument one is making at any given time.

So, with that in mind, what kind of Cobain Suicide Anniversary Piece are you looking to write? The first and most obvious choice is a pouring-forth of sheer emotionalism about your own youth. How did Cobain’s death affect you? Where were you when you heard he died? On the timeline from losing your virginity to your first heartbreak (reverse order is fine if you’re romantic by nature), where does Kurt Cobain ceasing to exist place? Could you shift things around a bit so his ascension into the Lord’s Own 27 Club is within a week of your pivotal experience of choice? “On the day Kurt joined heaven’s jamboree, I like to think he was joined by my hymen, playing the meanest drum fill on ‘Lithium’ you ever heard…” Something like that. God designed adolescence to have a surplus of emotional benchmarks; if you can’t find one to compare to death by shotgun, that’s a failure of imagination on par with much of the Foo Fighters’ catalogue. And you don’t even have the get out of jail card of having once been in Scream. Try harder.

And please keep in mind that an exercise in nostalgia doesn’t need to be hagiography. Have you considered taking the aggressively contrary approach? Focus on Cobain’s drug addiction. Focus on his poor parenting. Exorcise any sense of human empathy from your soul and call him a junkie piece of shit—because, if there’s one thing we can all agree on, as we pour ourselves a couple fingers of Jameson and cut another line, it’s “fucking junkies.” Oh, and call suicide “selfish.” Express anger as if his death were something done to you, the writer surfing the web of pain and formative memory, and not, literally, his immediate family alone.

Also, be sure to talk about nothing being the same. Now, “nothing” and “same” are fluid, so you can define either as starting (or stopping?) with the release of Nevermind, the release of In Utero, Nirvana’s appearance on Headbanger’s Ball (they, bucking the hyper-masculine world of hair metal, wore dresses!), the Rolling Stone cover, or, of course, Cobain’s death. All are good year zeros for our new post-event existences. All hail the new not fascist but admittedly still pretty white dawn.

When you discuss time (and the importance of Nirvana to theirs), gloss over the decade-regular reoccurrence of white men with irregular haircuts that arrived in the 1979, 1992, 2001—punk, grunge, the “new rock revolution” as those aesthetes at NME called it—the every-ten-years retrograde rock revival propped up as the savior of Western Civilization from the infernal blackness and gayness of disco, Michael Jackson, and electro-clash, respectively. Be sure to frame Nirvana as having rescued us all from Skid Row homophobia, when what Sub Pop publicists really loathed was synchronized dancing. None of these mopes had an issue with fellow Neanderthals with beautiful flowing long hair. If anything, Cobain led the critical reappraisal of KISS, the fruits of which are Gene Simmons today complaining on Twitter about the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame being too inclusive and listing all the things in this world less rock and roll than, you know, “God Gave Rock and Roll To You.” According to Simmons, they are legion.

Monetizing memory and remembered or idealized grief is hard, so sometimes you need to come at it sideways. Again, god bless the contrarian who’s got his own version—shared only by a few thousand other men in their late thirties—of, “Nirvana was overrated, so who cares.” You may get some angry comments, but you can always write those off in the youth-speak of “feels” or “well, looks like I’ve got somebody feeling some sort of way!” Youthful affectation on the part of the aging writer is a grand tradition. It’s why I say “grok” so much. So go ahead, drop truth bombs like, “They were just Hüsker Dü with better production.” Because the worst thing that could ever happen to any of us is a very popular Hüsker Dü with drums that sound like Odin patting his own belly.

It’s not important what your motives for writing this piece are—presumably, you’re paying rent and selling lifestyle. No problem: Converse is a fine brand, and energy drinks are gross but useful as a cultural signifier of who not to sit next to at a bar. I’m just in it for the pretty words. And if the lyrics to every song on Nevermind taught us anything, it’s that pretty words are enough. It was when Cobain aimed for coherence, on In Utero, that vague yet deeply relatable dysfunction became life-between-the-underground-and-the-deep-aristocratic-sea rote—callow bitching by a man whose talents deserved better. That’s why we adore the Albini production on the album, because songs about the disappointments of fame deserve dry-as-bone production to drive the complaint home. From Rapeman to “Rape Me” to talking shit about [popular hip-hop act du jour], we can always depend on Albini to present middle-management grievances in a medium palatable to the apolitical upper classes. Write about that, but be warned: Steve Albini can write some bullshit, too, and you may end up in a slander war on a Tape Op message board. And history bore him out on The Pixies, so tread lightly.

The safest way, then, to write about the 20th Anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s Death By Suicide, is to put on your cardigan sweater, the one with holes in the wrist to place your thumbs, sidle up to your laptop, take a long pull of craft beer … and lie. Lie about everything. This—life, I mean—isn’t a truth-telling competition, and no one’s going to thank you for your candor while turning mythology into content. Everybody in the world let their Rolling Stone subscription run out when their grandfather passed for a reason: these stories are oppressive. People, when they really think about it, dig the present in a major way. But the ones who do want to relive these fables? The ones who write to you and say how much they were moved by your story, how they felt the exact same way about Kurt and, man, you really nailed it? These people are Pearl Jam songs, dark maudlin shadows in a bullshit world—trust them least of all. I promise you they’ll bore everyone to tears at your funeral.

So lie. Don’t just say something that isn’t true, either—that’s Internet amateur hour. Write something that puts lie to decency and grace as a whole. Write something that gaslights truth itself. Make a list; make a biographical comic book; get a chest piece of the death scene, publish the photo on Instagram, and when people question it, keep a straight face as you maintain its journalistic value. Post a picture of what Kurt Cobain committing suicide would look like if he were a cat committing suicide. “Hang In There,” if you know what I’m saying. Forget good taste and morality, because that ship has sailed, my friend. Cats aren’t noted for their moral behavior, and there ain’t nobody left but us cats, hanging in here, sleeping in sinks, generally being adorable and, yes, it is fucking cute when we DJ.