Nobody died that year. Nobody prospered. There were no births or marriages. Seventeen reverent satires were written—disrupting a cliché and, presumably, creating a genre. That was a dream, of course, but many of the most important things, I find, are the ones learned in your sleep. Speech, tennis, music, skiing, manners, love—you try them waking and perhaps balk at the jump, and then you’re over. You’ve caught the rhythm of them once and for all, in your sleep at night. The city, of course, can wreck it. So much insomnia. So many rhythms collide. The salesgirl, the landlord, the guests, the bystanders, sixteen varieties of social circumstance in a day. Everyone has the power to call your whole life into question here. Too many people have access to your state of mind. Some people are indifferent to dislike, even relish it. Hardly anyone I know.

It’s one of the strangest, most elegant openings in contemporary American literature, as perfect and precise as the beginning of Lolita, The Adventures of Augie March or Guide. In these fifteen sentences, you can hear whispers of Woolf, Dickens, Camus, Proust, but in its astringent comedy and ruthless compression, it’s all nouveau roman. It’s a paragraph that immediately establishes a tone—emphatic but elusive, pleasing yet forbidding—that will not waver for the novel’s 170 pages11The length of the just published NYRB edition. The entire book, in fact, consists of similar, seemingly unrelated, and generally non-sequential, often juxtaposed or contrapuntal, paragraphs. If your mind is more mechanical than mine you might seek, or create, a pattern. It is episodic, but each episode is something closer to a petit mal seizure—brief, inscrutable—than to the installments of a television show. 22To imagine a possible Speedboat TV show, though, think Sex and the City directed by Chantal Akerman. No, I can’t imagine it either. Speedboat’s not so much plotless as it has too many plots, which Renata Adler skips along and through, pausing briefly and then quickly abandoned. “There are only so many plots,” she writes later. “There are insights, prose flights, rhythms, felicities. But only so many plots.” Anecdotes begin in the middle, often without ending. Things don’t “develop,” but an aura accrues. It feels like nothing more than drifting through a cocktail party, eavesdropping on conversations by people you don’t know but who are, alternately, wittier, more tedious, insightful, banal, melodramatic or sadder than you. They often seem drunk. They tell jokes badly. You never know what they’ll say. You’ll never really know them at all. This makes it oddly propulsive, an existential page-turner. You can easily read it in a day.

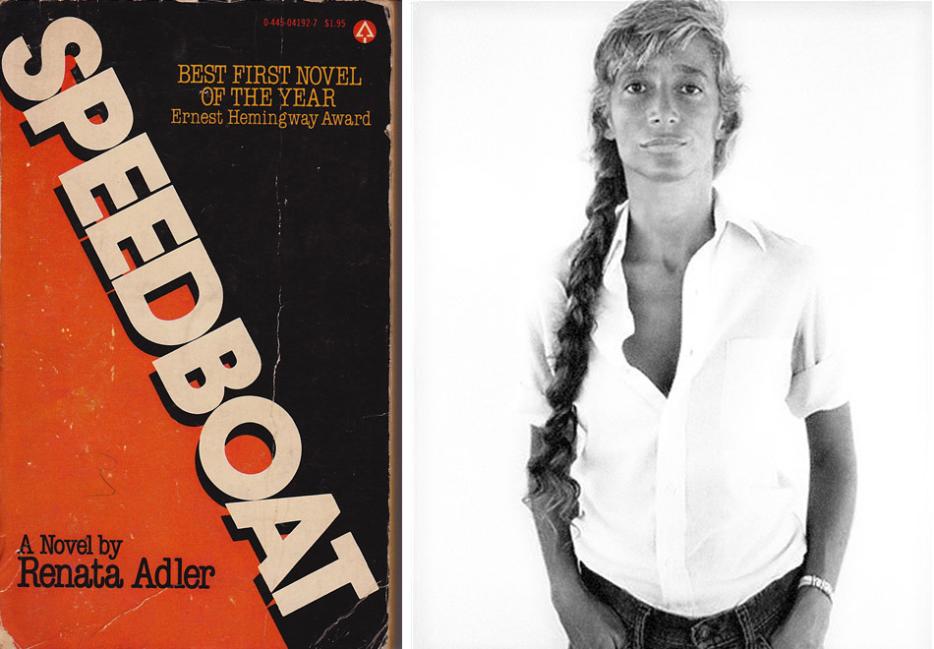

Decoding the novel’s odd intrigues, of course, takes far longer. “Nobody died that year.” What year? It took Adler, who was then a staff writer at the New Yorker, about five years to write Speedboat, publishing it finally in 1976. In the decades since, the long out-of-print novel has taken on the status of a cult object, but when it was first released, it was a bombshell. On the battered mass-market paperback I own, there are blurbs from Updike and gossip columnist Liz Smith (“This has to be the best book of the year”), and an author photo by Richard Avedon. It won the Ernest Hemingway Award for Best First Novel. (Prior to that, its third chapter, “Brownstone,” appeared in the New Yorker as a short story and won an O. Henry Award.) John Leonard, arguably the finest American literary critic of the day, wrote in Harper’s, “Nobody in this country writes better prose than Renata Adler’s. It is Lillian Hellman, young again; Joan Didion, with a tendency to giggle; Albert Camus, on one of his sunny days.” 33There are many other novelists, New Yorkers especially, who have inherited an Adlerian style or borrowed her effects: Elizabeth Hardwick, Gary Indiana, Lydia Davis, and Lynne Tillman all immediately come to mind.

Speedboat doesn’t reveal itself quickly, or often, and sometimes it dwells outside the realm of revelation entirely. These sentences fascinate like the gentle shifts in hue in a minimalist painting. 44“Reality, the truth about life and the mystery of beauty are all the same and they are the first concern of everyone.”—Agnes Martin Declarative sentences, mostly, but their declarations are opaque and oblique. They are interrupted with casual, almost weary, impudence—of course the city can “wreck it.” Everyone knows that people can’t sleep in the city. Or at least the people that the narrator, Jen Fain, consorts with, a ragtag, highbrow, occasionally vampiric, coterie of journalists, lawyers, professors, physicists, spies, politicians, doctors and psychiatrists that, of course, often gathers at Elaine’s. Yet these sentences build swiftly to a deadpan punchline, making the whole graf feel like a miniature, conceptual stand-up act. Delivered by whom, though, and for what audience? Fain, not yet named here, recalls the homonymic “feign,” but also suggests “faint” and that word’s double or triple meanings (the missing “t” exaggerates this effect). Like Adler, Fain is a reporter (unlike Adler, at a tabloid), and, later, a professor. Her commitment to both careers seems provisional. The demands of both professions irritate and amuse her and, wryly, she does not seem to be particularly good at either: “I am normally the sort of reporter who hangs around, or rather, tags along. I have never been good at interviews.” This is, on the one hand, a journalist’s novel (a muzzy category that includes everything from For Whom the Bell Tolls to The Paperboy), but it’s also, as a catalogue of incidents that go appear to go nowhere, a parody of one. “Seventeen reverent satires were written—disrupting a cliché and, presumably, creating a genre.” Is Speedboat itself one of these seventeen satires? Presumably. Like In Search of Lost Time, it’s sui generis. David Shields, 55Shields, who breathlessly praises the novel in both his recent How Literature Saved My Life and Reality Hunger, says he’s read Speedboat dozens of times and tried to figure it out by typing the entirety of the novel twice. I’ve only typed out the first graf, and only once. What does such an exercise teach you? Not what it’s like to write like Adler, certainly. Nor do you experience what was surely the agonizing effort of forming as beautiful a textual object as this. The pleasure of reading is doubled, however; your role as reader is expanded, extended. For a few seconds, you absorb Adler’s rhythm, a staccato cadence that’s simultaneously jarring and ecstatic. It’s physical, like hanging off of Terrence Ross’s back as he dunks a basketball, maybe, or sitting in Georgia Hubley’s lap while she helps you play the drums. long one of Adler’s greatest champions, is fond of quoting Walter Benjamin’s dictum, “All great works of literature either dissolve a genre or invent one.” Adler does both at the same time. 66In another moment later on, Adler amusingly mocks such dicta: “There they all are, however, the great dead men with their injunctions. Make it new. Only connect.”

In this first paragraph, Adler’s hints at the novel’s preoccupation with sleep—sleep as the seedbed of dreams, sleepwalking, sleep interrupted, sleep as a type of false narcotic, sleep as a false death. (Other obsessions in the novel that this opening doesn’t address: race, capitalism, the infelicities of the media.) “My life began, really, at college,” she later writes, “where I nearly always slept.” Adler proposes a kind of ethics of sleep. Anxiety keeps people up. Anxiety beckons people into action. Anxiety keeps people thinking. Throughout the book, Fain strives, and often fails, to do the right thing. But so many rhythms collide: worrying about others, about yourself, about failure, regret, the future. The sleeper’s always vulnerable, but so is the sleepless. In a dream, who knows what the right thing is?

Speedboat’s often considered a portrait of 1970s urban anomie. It’s undeniably of its time—characters frequently drop Valium, they listen to Judy Collins, there are allusions to Biafra and “The Troubles”—but it’s also thoroughly contemporary. Adler’s said that the book was written in a “panic tone,” and that phrase could also describe our current discourse, where apocalypse lurks around every corner. The background radiation remains the same. Others have noticed that the novel anticipates our jittery, twittery age, where we simultaneously read more and less—incessantly skipping from website to Facebook post to text message and tweet, rarely submerging ourselves in any type of narrative for any real time. Except for Jen Fain, maybe, the characters—rarely described or imagined beyond their names, ages, professions, and anecdotal meanderings—are likewise only free-floating, porous figures. Adler’s milieu and subject is “the chattering classes,” and her characters are composed only of chatter, their own neurotic, babbling speech. If that language feels familiar, it’s because we haven’t stopped using it. At least, hardly anyone I know.