It’s patio season! Perhaps you'd like to split a pitcher of beer? That's a trick question. Of course you want to split a pitcher, because who doesn't this time of year? But you might reconsider when it comes time to decide on what to fill that pitcher with. This is how relationships end, after all. This is when your friends must confront the person who drinks crap beer. Maybe that person is you.

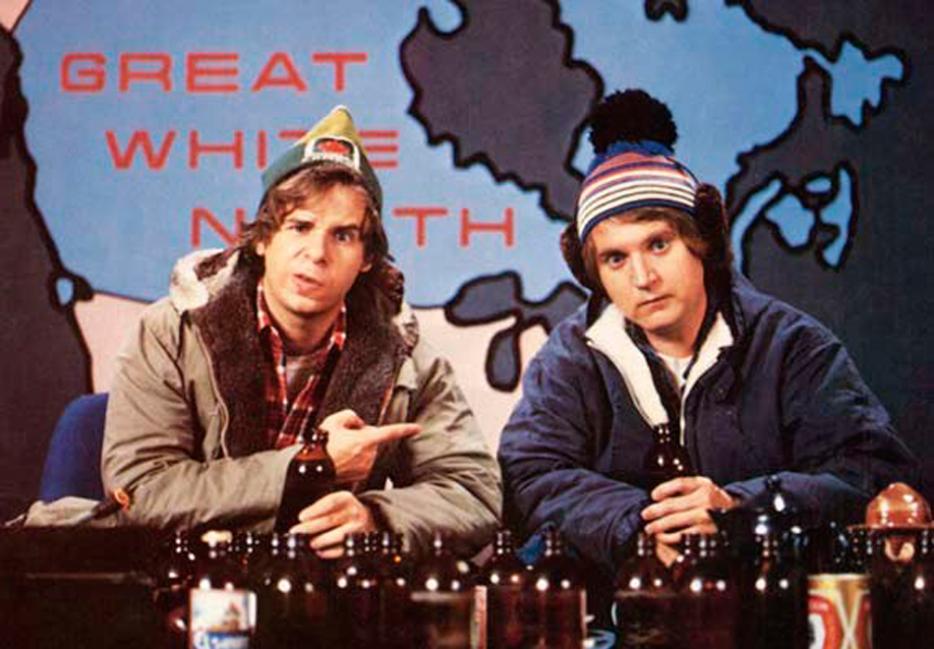

By crap beer we're talking about the mainstream stuff, of course—your Molsons, your Coors, an imported Heineken perhaps, or a Tecate from way down south. It's not craft, your more discerning friends will say. It's not filled with complex and exotic flavours or made from obscure hops! You might as well be drinking baseball stadium wine. Or water filled with leaves and twigs.

What is science for if not to give us better beer, wine, and liquor? “Modern scientists,” writes Wired senior editor Adam Rogers in his new book, Proof: The Science of Booze, “are only just beginning to distill the complex reactions behind the perfect buzz”—and this has created a whole new class of alcohol connoisseurs.

Like sex, science sells, and the superiority of one brewing or distillation process over another has proven a powerful marketing tool. If you had the choice, wouldn't you be tempted to drink a beer that’s been engineered using rare, bold-flavoured hops over something that wasn’t? A spirit that’s been handcrafted in small batches rather than mass-produced? The science of booze—of quality and craftsmanship—is an intoxicating narrative to the upper-middle class.

Quality means a lot of things, and to create a mass-market beverage that consistently tastes the same, year after year, you can't—scientifically speaking—fuck around.

The more science learns about booze and the process of making it, the more directions there are for brewers, distillers, and winemakers to take their craft. Rogers describes a special laboratory still that enables the artisanal distiller St. George—which is less concerned with consistency than innovation—to experiment with strange combinations of ingredients in a way that few previously could (or would). On the day he visits, it's an unusual sweet potato shochu that has been distilled, and the results are bottled on a shelf full of carefully labelled 800-milliliter Erlenmeyer flasks.

Elsewhere, master coopers—barrel makers—are studying traditional and non-traditional woods in an attempt to predict how aged liquor will taste. Another expert expounds on the merits of temperature—a lot of beer is served too cold—and optimal carbonation (which can greatly affect taste). And yeast? It turns sugar into ethanol, and thanks to science it's now an industry unto itself. Rogers visits the U.K.'s Institute of Food Research's National Collection of Yeast Cultures, a laboratory that specializes entirely in the study and storage of yeast. It houses over 4,000 different samples, up to 800 of them for brewing alone. Another, San Diego's White Labs, is sequencing the DNA of its yeast strains to determine where popular brewing yeasts originated, and, hopefully, to better understand the unique flavours that various yeasts produce.

Most associate this high level of attention and care with craft booze. But big brewers, too—makers of so-called mass-market swill—have leveraged the emerging science of brewing in no less impressive ways. "Just because Jack Daniel's comes from a chemical plant," Rogers writes, "doesn't mean it isn't a damn-fine-tasting chemical."

Quality means a lot of things, and to create a mass-market beverage that consistently tastes the same, year after year, you can't—scientifically speaking—fuck around.

A commercial brewery is really just a factory, according to Rogers, and operating a factory requires scientific rigour, too. Glenlivet, the scotch whiskey distiller, could never sell 1.7 million gallons in 2011 without it. On a visit to the Glenlivet factory, Rogers sees sensor packages everywhere, measuring temperature and pressure readings for each of Glenlivet's giant industrial stills. The company's spirit safes—where the good distillate is kept—lack the giant mechanical levers that a distiller would manually switch when proper whiskey starts flowing from the still. It's all automatic. "It may not be the romantic side that people want to see, but it's the practical side," Glenlivet's brand ambassador Ian Logan tells Rogers. "The only way you sell a brand successfully is consistency."

Or, in Rogers' words, "If the next bottle of Dewar's doesn't taste like the last bottle of Dewar's, you won't buy it again. The same is true for any big drinks brand, from Coors to Coca-Cola."

And, hey, there's nothing wrong with this. Really. As a scientific feat, it’s as impressive as sequencing the genome of winery yeast, or creating licorice infused beer. But many of us don’t see it that way. It's the difference between having an Egg McMuffin on a Saturday morning or going out for a hollandaise slathered brunch. Be it $12 eggs or some top-shelf bourbon, the supposed authenticity of something handmade is how some of us define quality, for better or for worse. When we pay good money for something, suggests Rogers—a fancy wine or a bottle of scotch, say—we want to know it was worth the price. As a result, many of us have lowered our expectations of what a cheap, mass-market drink can be. Surely not quality, the patio pals with which you’re splitting a pitcher might say. And definitely not as flavourful or interesting as a good craft brew, I'll give you that. But no less of a challenge to produce on such a mass-market scale. It takes skill to make something taste exactly the same, again and again, no matter when or where or how you have it, and just because the result is cheap doesn't make it bad, per se. If you've never ordered a Labatt 50 while everyone around you is drinking expensive wine, it's an experience worth having at least once. Even if you don't like the drink, you can savour the dirty looks.