One bright, early summer morning, just after my parents had been bilked out of their life savings by a huckster who preyed on fellow Indian immigrants, I asked my mother for five dollars so that I could get pizza at school. Choking back tears, she said she couldn’t spare it. Though we had never been close to rich, this sort of privation was new. In the months that followed, as further investments went south in the real estate collapse of the early Nineties, calls from debt collectors became a regular feature of life, promising complete financial ruin. A slice of pizza became the least of our worries. Rather, worry became ever-present, a grey, enveloping pall, obscuring both the future and hope.

Thankfully, those twin engines of the ambitious middle class—privilege and perseverance—revved up, and my family was fine by the time the new millennium rolled around. What proved more difficult to shake, however, was that low hum of anxiety at never having enough. We would, and still do, enviously watch food or travel shows, marveling at the breezy, seemingly unthinking way in which the crisply dressed, often white hosts would talk of dumping entire bottles of good Shiraz into a beef stew. When you are brown immigrants running from the spectre of poverty, nothing holds more promise than the very things white sophisticates find too gauchely ordinary to covet: mahogany furniture, a house in the suburbs, a Mercedes in the driveway, and wine you could afford to waste—those were the alien images I wanted to make my own. Only in mimicking the colonizer can you say you have mastery over them, apparently.

Yet if my parents can now occasionally both afford and stomach the odd indulgence, I did not, as I entered adulthood, keep up with their transition into modest comfort. To the contrary, I have spent the whole of my adult years broke—blessedly, not in the gnawing anxiety of poverty, but wrapped instead in the plain dullness of never having enough for that tiny phrase that encompasses so much of modern life: “nice things.” An initial lack of ambition, endless graduate degrees, and a hardly lucrative career choice mean that, while I am not poor, I have belatedly adopted that pose of so many privileged twenty-somethings in similar circumstances: in a world of precarity, soaring property costs, and endless indulgence, I hungrily consume images of luxury on social media while almost never being able to afford any of it. Making matters worse is that other “normal” markers of adulthood—a place of one’s own, a partner, a life—are all things that, for a variety of reasons which are all my own fault, I do not currently have. I am not oblivious enough to call this hardship or even allow it to register as a real complaint, but a sense of lack pervades my life nonetheless.

There is a skittishness to our imaginings of pleasure, a sense of desire always receding, jump cuts between scenes of perfection always hovering just at the edge of our consciousness, pulling us forward to live the life we have been taught to make dreams of.

But in my failures as an adult, I have still managed to acquire one of those symbols of having enough: a wine collection. Though calling it a “collection” likely aggrandizes it; it’s more of a wine accumulation. My rickety wooden rack is not full of you-probably-haven’t-heard-of-it gems from Chile, or expensive stalwarts from California or Bordeaux. It’s simply around twenty bottles, each around twenty bucks, sitting in a basement atop the chipboard TV stand we bought when we first arrived in this country. Certainly, there are a couple of bottles dear to me—a Riesling bought on a wine tour with much-cherished friends; a bottle of Italian red given to me upon completing my PhD, to be opened when either the friend who gave it to me or I first publishes a book—but even they are not what connoisseurs would consider special, or even noteworthy. But then, I am not an oenophile. As much as I appreciate wine and like to drink it, I’m not building a monument to good taste—it's a library of possibility.

*

For all its modesty, my collection has taken on a strange position in my imagination, becoming a synecdoche of the good life, manifesting in micro what I cannot have in macro. It is my own inverse telltale heart: not a locus of guilt, threatening to pull me into some foreboding darkness, but instead a repository of hope. Wine always evokes the pairing—food, obviously, but to be matched with something else, too: an evening, an event, a moment, another person. In my imagination, I experience a low-rent version of a bibliophile retrieving a perfect book to give to a friend: “Ah, seafood pasta? A birthday? A date?” I picture myself asking others. “Yes, I have just the thing for that!” It is precisely the endlessness of the list that makes the drink such an inexhaustible canvas, the image of a collection becoming the connective tissue between my life as it is and how I want it to be. Each dark green or clear bottle inevitably conjures the chance of experiencing what to my mind is the perfect cliché: that too-common Instagram trope of rays of sun filtering through glass, casting bony fingers of light on a rough wooden table or white linen.

Such light is always moving a bit, lost for a second to a passing cloud, then back again, a simple, quiet dance. There is a skittishness to our imaginings of pleasure, a sense of desire always receding, jump cuts between scenes of perfection always hovering just at the edge of our consciousness, pulling us forward to live the life we have been taught to make dreams of. But our cultural landscape is now saturated with these tropes of aspiration, too. If social media ostensibly began as something like “life logging,” it has perhaps shifted its field of view from the point where we stand to the horizon—no longer “this is the sandwich I am having for lunch,” but rather: isn’t this the sandwich you wish you had?

Is it then fair to say that, in this second decade of the new millennium, between those two poles is the screen? Each spring, my Instagram feed blooms bright pink, images of rosé and the seductive allure of life’s greatest pleasure—day drinking—melding with crostini and flushed limbs, splayed out across tables or lawns. Scrolling through it on a warm Sunday evening, you can start to piece together the collective yearning of a generation. Food and drink in particular have become these loci of desire because they are so easy to perform, universal, but infinitely capable of eliciting want. Yes, we are always hungry, but we never stop craving the feeling of craving itself, seeking out the things that spur us toward desire. Perhaps it’s how temporary food and drink are: As Edward Lee put it in a Mind of a Chef episode (titled “Impermanence,” of course), the gourmet is a simple, accessible metaphor for mortality. A generation was told that theirs will be the first to not exceed the wealth of its parents: artfully arranging food and, just before it is gone forever, taking a picture of it, is a futile and entirely understandable attempt to hold on to pleasure.

Wine is the goal of a life well lived, but also a way to temporarily forget you aren’t there yet.

It is easy to be cynical about this kind of obedience to the image, but our hope is forever caught up in this tripartite movement: between our self in the present, our visions of the future, and the kaleidoscopic images of cultural desire at large. We stumble forward in search of happiness, trying to find some way to make the three connect. We are only ever the space in between where we are now and where we wish to be.

*

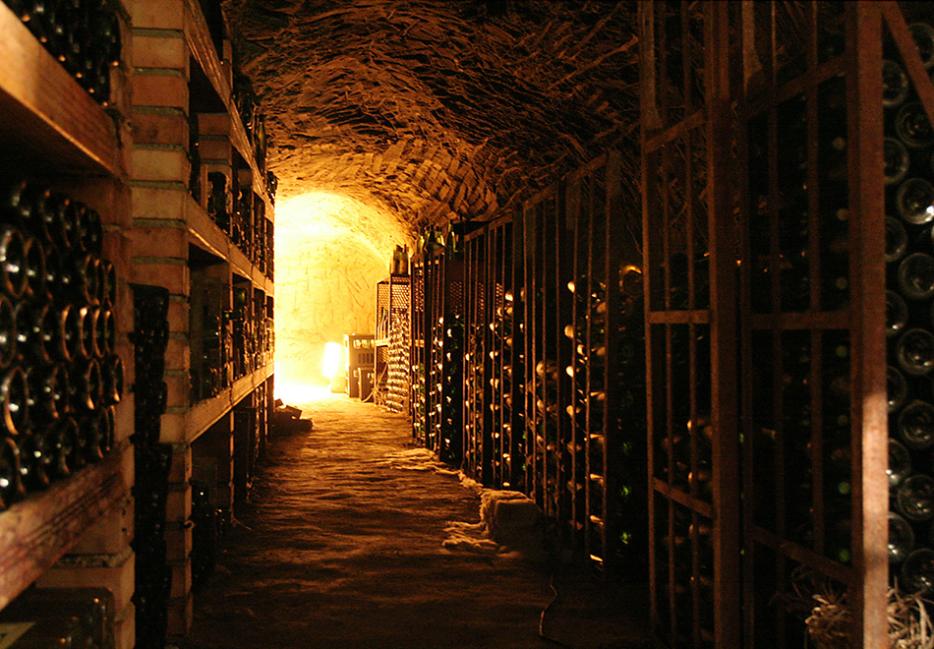

In the wine catalogues that I have taken to eagerly reading and re-reading, a review of a Barolo ends with the helpful suggestion “Drink 2018-2040,” as if this is an appropriate span of time to consider for a thing you consume and not better suited to, say, forestry. Too much is contained in such terse, simple instructions—as if it doesn’t immediately conjure, in the mind of the perpetually broke and hopeful, a dark wooden cellar, a tasting table, and a time decades into the future in which a life replete with no end of sensory pleasure finds a moment of rest, a reason for joy, and thus spills out a purple liquor into fine glassware and, before the first sip, a knowing look at a partner to acknowledge the waiting, the accumulation, the sheer span of the years that has led to this point.

Wine is the goal of a life well lived, but also a way to temporarily forget you aren’t there yet. And somehow, my life hasn’t quite turned out the way I was hoping. I don’t, and will probably never have, a down payment for a home. I do, however, have a 2012 Barosa Valley Shiraz I am saving for a good steak or perhaps, one day, someone with whom I can talk while our faces are lit by candles. I like that I own almost no clothes worth wearing but have too much Cabernet Sauvignon. Being an adult is about making compromises, and that is a good one. I’ve missed out on so much—so frequently shied away from life, and love, and opportunity—but at least I have a cheap bottle of Viognier that some friends and I will use to set fire to a too-hot afternoon in August, a headache and dry mouth following us into the evening, the haze of alcohol smearing the memory, etching the blurred shapes and colours of the day onto the walls of our minds.

A bottle of wine isn’t a noble thing, not really. It is mostly solace, temporary relief, just an object into which one can pour one’s desire for more. It can help, though, to gather such things: to collect them, tuck them away safely somewhere—neatly lining up one’s hope on wooden racks, talismans of something better always ready at hand.