I would love to have had more personal experiences with Mavis Gallant, but as it turned out, I just had two.

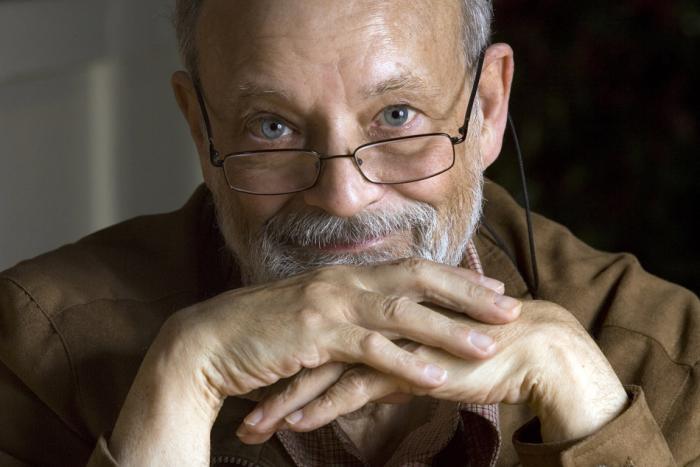

One was on October 27, 1996. Gallant was in town for the International Festival of Authors. She hadn’t lived in Canada since 1950, and didn’t come back much, but her publisher had just put out her Selected Stories and so she returned for an event that would feature her and Mordecai Richler. It was just the two of them, sitting in comfortable chairs on stage.

The talk was easy, but the words were not. I remember being enthralled throughout, seeing these two lions purr and growl in each other’s company, though I don’t now remember too much of what was said. They did talk about Louis-Ferdinand Céline—I’d never heard of the guy before, but the way they spoke of him, and the grace of his language, suddenly qualified him as one of my favourite writers (his brand of nihilism, I would discover, was expressed so colloquially, it made for a level of realism later writers would struggle to emulate). One of them brought up the issue of his quite rancid anti-Semitism, and both as quickly dismissed it. I was young and judgmental, always looking for reasons to dismiss people because of their sexism or homophobia or excessively conservative views on this or that. But this was a man whom even the head of Nazi propaganda in Occupied France denounced for his “savage, filthy” anti-Semitism and his “brutal obscenities,” and here were Richler and Gallant praising him as one of their favourite writers. It was my first lesson in the distinction between art and personality, and that became the fundament of everything I’ve thought about the issue since.

“I’m not sure that art has a purpose,” Gallant said. “I wonder if you’re not taking a Canadian puritan attitude, that it has to have a purpose, that it has to have value, otherwise what’s it doing?”

But that wasn’t the personal part. Because I was vaguely associated with the publishing industry at the time, I got to hang around in the festival’s Hospitality Suite, in the penthouse of the Harbour Castle hotel, after each day’s events. At about 11pm, I went up and saw Gallant on a sofa by herself. I’d read her Selected Stories by this time, and had some impression of her character from her writing. I assumed she wasn’t the sort of person who had time for much nonsense, or small talk. And since I thought I was quite thrillingly literate, I decided to sit beside her and make some big talk.

She would have been in her seventies at the time, and probably saw the look in my eye. “Would you like some tea?” she asked, before I was able to start talking about appropriation of voice as it relates to nationality (or some other equally undergraduate concern of mine at the time). I said I would. So she got up, found a pot, some tea, some boiling water, and two cups, and we spent the next 20 minutes chatting, about Paris, where she lived, Toronto, where we were, and Montreal, where we had both grown up. I learned the value of small talk that night. It bought me 20 minutes on a couch with Mavis Gallant. I’ve been an enthusiastic proponent of it ever since.

That was actually the second time I had spoken to Gallant. The first was at the beginning of 1988, when I somehow found her home phone number and called her up to ask about the purpose of art for a series I was putting together for my school arts journal. I had read her collection From the Fifteenth District, maybe picked up on a couple of things about mimetic vocabulary–using the same sort of diction in the narrative voice the characters being described might have used themselves, without ever having to break off into dialogue—and understatement. (I still remember the casually presented clause in the title story about a character having been temporarily crucified to a cart for failing to salute a superior but equally young officer in the First World War). But mostly I just thought it was cool that she lived in Paris.

I spoke to more than a dozen people for the project, and the likes of Alex Colville, Robertson Davies, Northrop Frye, and Dorothy Livesay gamely answered, mostly trying to be gentle with me (though Morley Callaghan, I see now, was a little on the dyspeptic side). Gallant took my question apart at the root, introducing me to a concept I had not yet considered. I’ve just re-read what she told me back then, speaking into a cassette recorder with a suction-cup microphone attached to the receiver, having been ambushed by a kid who didn’t know enough to set up the interview in advance with a publicist. And since it’s never been published anywhere but that little student journal, I thought I’d include her off-the-cuff answer here in its entirety.

I think we read, watch, and look if we have a natural inclination in that direction—very often if we are brought up to it as children. I really know more about writing. I don’t think I would have been a writer if I hadn’t read enormously as a small child. I think the first books you read almost set the tone for what you’re going to write. The habit of reading is something you can’t thrust on children but if they take to it, then everything else opens up. I had these things very young. My father painted and I was taken very young to Canadian painting, the snow and the trees and things. Some of my first memories, in Montreal, are of my father picking me up and showing me a painting of snow and trees, you know, the typical things that people did in those days, and saying, “You see, snow isn’t white, it’s blue, it’s mauve.” For some reason this stuck in my mind. I think you have to make it a normal thing for children to go and look at painting and not a thing that is a bore for them or something that they just do with their parents.

I’m not sure that art has a purpose. I wonder if you’re not taking a Canadian puritan attitude, that it has to have a purpose, that it has to have value, otherwise what’s it doing? The purpose of art is to enhance your life, to make your life richer, to give itself a meaning. I think that art is an aim in itself, I think that writing is an aim in itself without it being useful like painting a house. I think it’s a different thing.

I notice when I’m in Canada people still say, “It’s a nice day but we deserve it.” Go to the Toronto zoo one day and watch how some people behave with the animals. They’re constantly bothering them, pestering them, and waking them up because they should be doing something. I remember seeing a sleeping tiger three years ago, and a woman rattling the cage and saying, “He’s lazy, that’s all he is, he’s lazy.” I think it’s a bloody marvel that art in Canada is as much as it is when you think of everything else people had to do to get the country going. Art does not just spring spontaneously from the track of a railway, that just doesn’t happen. I think it’s marvelous that it does exist. Jung gives, among the prescriptions for happiness, an appreciation of art, and appreciation of nature—the ability to appreciate. I would be very unhappy if I were cut off from any of it.

I write because I’m a writer, and I do what I do. What else would you like me to do? I don’t think that people should read for anything but pleasure. You know, when high school students write to me from Canada and they say, “I’ve got a project and my project is you. Please tell me why you began to write, who influenced you, do you write with a pen or a word processor?” I write back and say get all this from your library, and what is more, don’t read me because I’m a project; please don’t do it.

I think that if you say, “What is the purpose of art?,” then you’re trying to say that art developed out of a purpose, and that’s a god-like conception, isn’t it? God created man and he created art. One could get into deep theology here.

Sometimes people tell you that they’ve read your work at a certain time in their life, and that’s always very moving to me. But I don’t sit down to write something to help someone. I just write it. I certainly don’t think it should harm anyone, which I wouldn’t like at all.

I remember the pause as I waited to see if she had anything else to say on the subject. She didn’t, so she broke the silence by saying, “So, Bob’s your uncle.” It was something else I’d never heard before. I thought she actually might have known some relative of mine from her time in Montreal. I wish I had written down the absurd who’s-on-first routine that followed, but I feel sure she didn’t hang up with any more sanguine opinion of Canadian youth of the day than she started with.

I’m glad my time with her came when I was as young as I was. I think I benefitted from some sort of maternal instinct on her part because reading her interviews with adults, say in the Paris Review, she doesn’t pull her punches. She was a flinty forebear of Margaret Atwood, and a perfect foil that October night for Mordecai Richler.

Knowing that she was in her nineties, and that the other Canadian short story writer had just won the Nobel—though I don’t know what they thought of each other, I had for years entertained the notion that these two women were the Canadian José Saramago and António Lobo Antunes—the single consolation of her impending mortality was that it might spark a renaissance in her reputation. I won’t start in on that now, trying to itemize her strengths and place her in the pantheon of 20th-century literature. But I hope some folks do, because she sat astride it with a confidence that belied the effort it took to keep her seat. Instead of raising a glass to her memory tonight, read a story. Mine’s going to be “When We Were Nearly Young.” I think I’ll read it on a couch, with tea, set for two.