Thirty years ago, fortified by several intoxicants and the tetchy beleaguering of Bob Geldof, an era of British pop stars rushed to record together under the name Band Aid. The resulting song “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” was a nightmare-poem of colonial lamentation, Kipling with feathered hair—but it became the biggest-selling single in UK chart history, a height most of the participants would never approach again, raising millions of pounds for Ethiopian famine relief. The concept caught on. USA for Africa orchestrated its own mega-single, 20 seconds of shivery Michael Jackson vocals and seven more minutes of Billy Joel and Steve Perry attempting to get hymnal. There was a glut of these charity records for a time, ranging from “fairly diverting Lou Reed cover” to “at least they got Kate Bush” to “Fred Durst crying ‘Somebody tell me what’s going on? We got human beings using humans for a bomb!’”

The bellowing condescensions of the charity single have been easy sport at least since The Simpsons did “We’re Sending Our Love Down the Well.” And although Geldof et al updated the most egregious lyrics—there’s even a stray reference to the afflicted region of West Africa, rather than casting an entire continent and 54 countries as one piteously helpless mass—the new Band Aid 30 version of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” has little to recommend it beyond some money for Ebola victims. Sinead O’Connor is the only contributor who manages to voice the terror of illness; you’re better off listening to the single by an actual West African supergroup, including Salif Keita and Oumou Sangare. But “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” has already returned to #1 in Britain. With its overpowering weightiness, the clash of so many different musicians, a hit charity record reveals something about modern pop composited. I couldn’t think of a better person to discuss them with than the writer Tom Ewing, whose Popular project—a critical account of every chart-topping UK single—is currently midway through 1999. Sometimes he also writes about Pokemon.

*

"Do They Know It's Christmas?" and "We Are the World" came long before my time, but not quite yours—do you remember your initial reaction to each single?

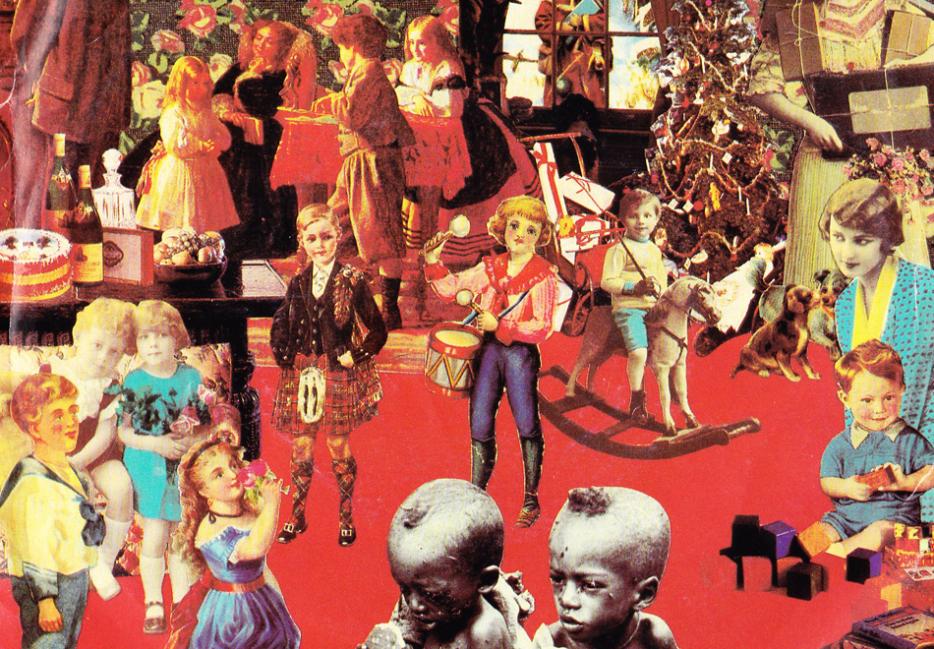

I didn't have a copy of Band Aid, but my friend Chris did, and one evening for whatever vindictive or transgressive reasons we might have had at 11 we graffitied the sleeve with glasses, fake beards, all that kind of stuff. It was quite a pious sleeve, a classical scene of the infant Jesus, so plenty of scope for that. It sums up the reaction well enough—obviously we owned it and were in slight awe of it and also resented it a bit. I don't think I noticed it as a song, it was rather dreary, but all the mocking of That Line and so on came much later.

The other thing about it though was that the idea of all these massive stars getting together was terribly exciting: with hindsight a bit like a Marvel Comics crossover event, Secret Wars or something, though I wouldn't have had the language for that. But at the time I was reading Smash Hits magazine, and that and the news media were fascinated by the process of it—the momentousness of getting all these people together. Smash Hits did a big reportage feature on the recording of it, which was a beautiful tightrope walk between "this is massive and something new" and its usual "take pop stars down a peg" mode.

"We Are the World" I remember hating. I had absorbed a lot of lazy British playground chauvinism about the USA, and my feeling was that this was Americans nicking the idea and making it even longer, and even duller. Again, at age 12 the worse lines didn't stand out. “We Are the World” obviously had major star power, but those stars were very remote to me in any case—in Britain you mostly experienced Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, etc. via video, you wouldn't actually see them on TV performing live. I think also “We Are the World” has a different flavour, even beyond the obvious fact that it's a much, much more diverse line-up—it's a genuine attempt to pull together the absolute biggest stars, not just current stars but all-timers—and there's been an effort to create something timeless. Whereas “Do They Know” is very much not consciously attempting to do that, it's an immediate response and a pool of talent drawn from a particular generation—post-post-punk—of stars. Which made it feel very urgent, a pop event even if the record didn't sound like what I wanted from pop.

Yes, that's one of the things that strikes me now about "Do They Know," how much it's the result of a specific moment in pop—and aside from Bono or George Michael, most of the contributors would soon be fading from view.

Every charity record is political in that it implies a philanthropic solution to sufferings of war or deprivation, but I was trying to think of ones that took a different approach like "Sun City," which was bitterly controversial at the time and seems semi-forgotten now. The artists who got called out for flouting the South African cultural boycott flinched away from it; it also won the 1985 Pazz & Jop poll, despite only nominally being a coherent song. ("A long-cherished fantasy of really serious fun," as Robert Christgau's essay put it.) But the weirdness of the lineup stands out even now—Bob Dylan and Miles Davis, Lou Reed grasping Hall & Oates by the shoulders, Joey Ramone rasping "constructive engagement is Ronald Reagan's plan"—and it resisted apartheid in its halting rap-rock form as much as the lyrics. This is not really a question, but I'm curious about your response anyway...

I think what you see in the early charity records is a kind of evolutionary process—trying different things out to see what works, and "what works" generally means "what the public will buy," since the measurement of success is in the money you can publically claim to have raised. That's another way "Sun City" is unusual—it's an awareness-raising record as much as it is a fund-raising one. Maybe more so. It's asking the question: can the Band Aid format of stars together in the studio be applied to, essentially, a protest song? And I think it's a weird sort of success, but it doesn't replace the dominant Band Aid strain where the politics, as you rightly say, are very much implicit.

The charity single is a creature that's flourished in an age of supposedly fractured consensus—where there is, we're often told, no central storyline to pop music anymore.

There are other variants too being tried out—the guys who used to be 2 Tone Records in the UK, Jerry Dammers of the Specials, and Madness, organized a double A-side single called "Starvation"/"Tam Tam Pour L'Ethiopie." Here the basic concept was, "What would Band Aid be like if African musicians were actually involved?" So you've got the more, for want of a better word, authentic variant, and the more explicitly political variant. And as time goes on it turns out the Band Aid model is itself an imperfect version of what becomes the dominant strain in the UK at least—the charity cover version. It turns out that writing original songs for major tragedies is something of a fraught, foot-in-mouth business, and you can't expect Michael Jackson to be available every time. Whereas there's a bank of existing, vaguely hymnal rock classics that everyone already knows, and you can get a crowd of stars along to do "Let It Be" or "You'll Never Walk Alone" without too much difficulty. It's more efficient, if musically pretty ghastly. My impression is that never really took off in North America, though—did the charity cover record become a thing there?

And even "Sun City," attempting to unite the militant tendencies in various forms of pop, succumbs to another Dramatic Bono Moment. (It's still a little striking to hear "How come we're always on the wrong side?" during a single with some of these names attached.) The subsequent use of cover songs is interesting because it sometimes highlights a musician who would never get near the Top 40 otherwise: Lou Reed with "Perfect Day,"or John Cage a few years ago. "Charity" as a kind of metafictional gesture. I suppose "Candle in the Wind '97"works similarly, although I often forget it even was a charity single, such do the awkwardly inserted Diana signifiers obscure everything else.

That practice did take hold on both sides of the Atlantic, I think—the big supergroup responses to 9/11 adapted "What's Going On" and "We Are Family." Maybe it's just that charity records have always been more numerous in the UK. They fell out of favour in the late '90s (because everybody saw Pulp's "Bad Cover Version" video?) and then returned to prominence somewhat, but what would you ascribe that to? Is it simply because the sales-centric nature of the UK singles chart rewards novelty and spectacle, e.g. the annual contest for a Christmas #1, whereas the American one tries to quantify consensus via radio airplay?

You're right—it's the sales vs. airplay thing. The UK charts are a mechanism for whoever is buying records at a given time to have their tastes publically recognized. They worked best when a bunch of diverse interest groups bought singles and the charts reflected that—the late ‘70s, for instance, where new wave and disco and corny AOR pop all mingled more or less equally. But a sales chart has a second unintentional role—it doesn't just reflect what's happening in music, it reflects what's happening in any part of popular culture that spawns an associated single. It's an erratic, but real, cultural seismograph, and charity records are one of the three great ways of exploiting that (the others being film themes and reality TV shows).

Charity records are a way of turning news into pop. That's always been a thing in the British charts—the very first British chart, which came out in the week of the Queen's Coronation, included a smarmy thing called "In a Golden Coach." But charity hits worked out a way of doing it regularly. They had a similar decline in popularity, though, but a couple of large charities got around it by linking singles to bigger TV events. The Comic Relief records, which come out every two years, are a fossil record of charity strategy —moving from celebrity team-ups with comedians, to boy bands doing upbeat but awful covers, and ultimately—with Tony Christie's "Is This the Way to Amarillo"—just reissuing an old ‘70s hit and sticking the comedy in the video. That was a colossal success—way more efficient than a Band Aid.

But it's interesting you mention consensus, because the charity single is a creature that's flourished in an age of supposedly fractured consensus—where there is, we're often told, no central storyline to pop music anymore. And yet the charity record ignores that. In the UK, they did it mainly by being sold in supermarkets, near the tills, like a lapel pin or commemorative wristband. But the drift from original song to cover version helps create fake consensus too—if you pick songs from 30 or 40 years ago, you have license to ignore the enormous changes in music since. One of my favourite moments on any Band Aid single is Dizzee Rascal's little rap on Band Aid 20. It's not good—though there's a basic pleasure in hearing Dizzee strut and squawk on anything, however brief—but it's an acknowledgement that music had shifted on its axis since 1984. There's nothing similar on the 30th anniversary edition. Could charity records ever have "kept up," I wonder, or was that never the point?

I'm glad you mentioned that Dizzee Rascal verse, because I just listened to the Band Aid 20 version again and was struck by how it gestures towards "currency" circa 2004, in the strained manner of a Mojo year-end list. The production all sounds rather subdued, almost minimalist. Whereas Band Aid 30, well, Sam Smith phrasing "Christmas time" like an alien studying human speech is the synecdoche, isn't it? I find the whole thing conservative—not just in its vaporously tasteful aesthetic, but the half-measures hedging against some justified offence. So Angelique Kidjo appears for a handful of seconds, and they've revised the arrantly ignorant lyrics about nothing growing in Africa. But "tonight thank god it's them instead of you" did introduce a note of cynical ambivalence to undermine the self-congratulation—whether you love or hate them (and I really hate them), Bono's vocal stylings have always been, let's say, shameless. "Tonight we're reaching out and touching you" just sounds like a line for One Direction that alarmingly ended up inside the mouth of a middle-aged man. To be charitable.

I still think the only person who's managed to solve that lyric was David Cross, on the "Do They Know It's Christmas?" cover Fucked Up shepherded: "Tonight thank God it's them instead of Jews." (Also featuring Tegan and Sara!) The other notable aspect of Band Aid 30 for me is the number of women in the lineup, versus almost none the first time around. If sales charts represent a crude cultural seismograph, does this say something about how much female stars dominate pop right now? I think that's true in North America and the UK alike, but you have a closer understanding of the latter context. (We're both circling around the same ideas as Top 40 Democracy, Eric Weisbard's new book.)

You're right about the current dominance of female stars—in the UK it's a trend that's built for close to two decades, ever since the Spice Girls. (This roughly coincides with the rise of stock complaints by critics that the charts are shallow, rigged by marketers, no longer a “true reflection” of pop music, etc. Hmmm.) In charity terms it's interesting, because pop charity in the Band Aid sense is hugely rooted in the heroic male rock star stepping in and getting something done—usually with a certain amount of tearful humility, I grant you. But from Geldof on, men tend to present themselves as the motivators of charity rock, and some of that is the way it presents caring as an exceptional act, something that cuts against the day-to-day selfish business of pop life. And traditional gender roles, obviously, frame caring and charity very much as women's work.

The most commercially successful female-led charity record I can think of is "Love Can Build A Bridge"—Neneh Cherry, Chrissie Hynde and Cher covering a track by the Judds for Comic Relief. It's lachrymose and forgettable, and with those three women singing on it it really shouldn't be—which brings us back to the foundational problem of charity records. The music doesn't have to be especially good, and so it often isn't. If you're in a situation where you can get Neneh Cherry and Chrissie Hynde doing a song together—with Cher!—the possibilities for making a great record ought to be wide open. And it simply doesn't happen.

Do you remember any favourite charity-record moments we haven't gone over yet? The Bowie/Jagger cover of"Dancing in the Street" ("SOUTH AMERICAAAAA!") has a certain low-camp appeal. "We're All In the Same Gang" is actually, like, good. And while "Voices That Care" survives mainly as a punch line for music nerds—it's the pop equivalent of some alchemical bioweapon—I love how mismatched and incongruous the lineup sounds, even on paper. Michael Bolton and Garth Brooks and Celine Dion and...Will Smith...plus the Pointer Sisters...with a soulful Kenny G solo? It reminds me of the Defenders, the Marvel superhero team made up entirely of squabbling loners. The Doctor Strange analogue would be Little Richard, obvs.

I don't know if there are any great charity records I've not mentioned, but I know the worst. In 1985, Northern Soul producer and prominent Doctor Who fan Ian Levine was outraged at the rumoured cancellation of the show. He pulled strings to put together a Band Aid-style ensemble of marginally famous musicians and embarrassed actors under the name Who Cares to record the self-penned "Doctor In Distress" in protest. Money went to Cancer Research. Not very much money, I fear. It's a dire warning from the beginning of the charity pop era about how badly these things can go: without proper stars, or a good cause, the wheels come off completely and the project tanks. But in a weird way it also testifies to the strength of the idea and the good in it—the tiny hope that from unlikely combinations something memorable might bloom. Even if it's often memorable for quite the wrong reasons.