The defendant has misplaced his lawyer. He stands behind the long wooden table at the front of Courtroom #300 and lifts his hands towards the fluorescent lighting, his shoulders shrugging around his ears, rippling that skin at the back of his neck into three distinct lines. Mac is a large man with a barrel chest, his head bald except for two tufts of salt and pepper hair that stick out at the sides, like the horns of a bull. His arms remained raised. The courtroom remains quiet. The plaintiff, Ted, a middle-aged man wearing a black golf shirt, who won’t be mentioned from this point on, continues staring straight ahead. Beside Ted is his council, Sandra, a thin young woman in a grey pantsuit and sensibly high heels. She puts the unpainted nails of her thumb and index finger to the bridge of her nose and squeezes.

“What’s the number again?” Judge Mary asks.

“416 … ” Mac says and recites his attorney’s phone number from memory. The court reporter calls, hangs up, calls it again. Then he twists in his chair and looks over his shoulder at Judge Mary.

“It’s going straight to voice mail,” the court reporter says.

Justice Mary exhales, her breath rippling the bangs of her shoulder-length silver hair. This is part two of a trial continued from last August. The conflict in question originated in 2009. “This is what we’re going to do,” Justice Mary says. “The trial is continuing today, sir. Do you have any more testimony?”

“No. That’s pretty much all that happened,” Mac says. He looks at his phone, slips it into the holster clipped to his belt. When he looks back up he’s surprised to see that Justice Mary is staring at him.

“You’ll have to take the stand so your cross-examination can begin,” Justice Mary says.

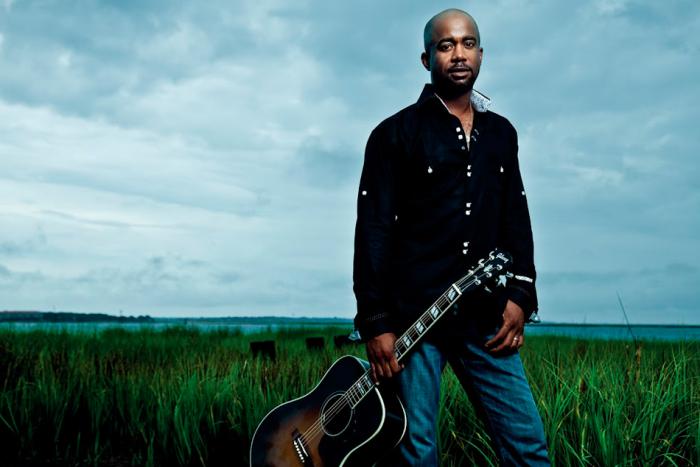

Mac nods, takes the stand, gets sworn in. He makes fists of his hands, rests them on top of the witness stand, and leans forward. Then he pushes shallow breaths through his nose, tilts back his head until his chin points almost directly at Sandra. It is easy to imagine a large golden ring through his nose and cartoon bursts of steam coming out of his nostrils—Mac the Minotaur.

It’s just as easy to see Sandra as a sapling, young and green. But this too could be an act. She opens one of the six binders stacked neatly to her right, flips pages, looks up at Mac. Then, instead of asking her first question she fills a white Styrofoam cup with water from a stainless steel jug. As she drinks, the cup hides a smile. It is no longer there when she sets the cup down, flips another page, and clears her throat.

“So. Mr. Minto. You’re very experienced in sourcing products from China for Canadians?”

“Yes.”

“Salad bowls? Cell phones?”

“More so on the electronics, yes.”

“You have strong relationships with China? With Chinese manufacturers?”

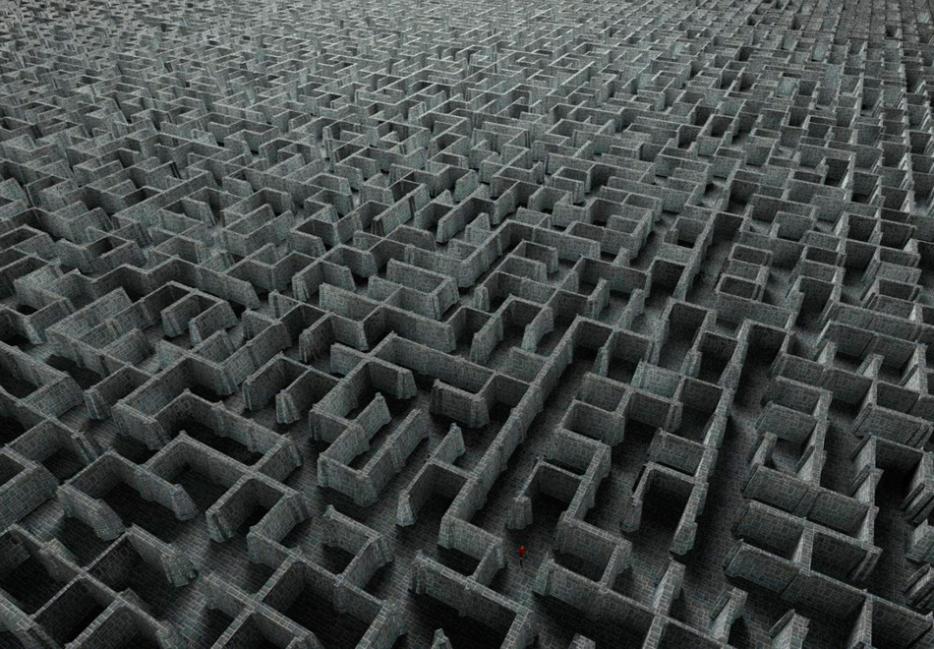

“Yes?” Mac says, narrows his eyes to slits and begins to understand that Sandra is leading him into a trap, a labyrinth of facts. For the next thirty-five minutes, this is exactly what she does, presenting evidence as an unquestionable sequence of chronological events. Mac agrees that in September of 2009, he was hired by Ted’s company, Waffleland. That he agreed to travel to China, to source and design a waffle-maker that met specific technical requirements. That once the prototype was approved, he would oversee production of 220 units. He was paid a lot of money to do this, $50,125.

“You were paid three-thousand for consulting, four-thousand five-hundred for costs, six-thousand for travel to China. As well, a ten-thousand deposit to a factory in China. That leaves $26,625 unaccounted for. Where are these funds?”

“I don’t have these funds.”

“Where are they?”

“In China!”

“Where in China?”

“The factory.”

“Did you submit documentation to this effect?”

“No.”

“So you didn’t provide this document?”

“It’s in Chinese.”

“Where is it?”

“I haven’t provided it.”

“So you never told the court about it?”

“I was never asked.”

“You never told?”

“I was never asked.”

“You never told?”

“No. I have no documents.”

“No packing slips? No tracking numbers? No emails?”

“I have nothing here.”

“Where is it?”

“In China!” Mac says, huffs, stares at Sandra, his blunt thoughts about her easy to read.

“I’m going to put it to you,” Sandra says, takes a sip. “There never was a prototype was there?”

Mac corrects his posture, stands up straight, takes a breath. He has failed to convince even his own lawyer to show up. He has presented little evidence to prove his innocence, while Sandra has done an excellent job of establishing his guilt. And all I want, what I crave to see, is for Mac to throw up his hands and yell at the top of his lungs that he took the money. I would also accept claiming to have spent it bribing Chinese politicians. Or even buying favours from a woman he met in a bar. Any of these would redeem Mac in my eyes. I suspect it would fundamentally alter how he sees himself as well. As Mac stands there, silent, motionless, trying to decide how to answer Sandra’s question, there is something in his face, a sadness, maybe even shame, which speaks of the potential for nobility. That some part of him is aware that this is an opportunity, the kind rarely presented, to wipe the slate clean, start again, become the stand-up guy he knows he has inside him. But it’s not to be.

“That’s not correct,” Mr. Minto says.

Sandra instantly flips a tab in her binder, her fingers finding a passage like a butcher sharpening a knife. Mac’s upper body slumps forwards, his large meaty hands grip the sides of the witness stand and his eyes turn from slits to ovals. He seems to realize what he’s done, that he’s lost his only way out, that he’ll be trapped inside the labyrinth forever.