When Hollywood directors of the 1940s needed a character to glower upwards, rat out their boss, or wail “I didn’t do it, I swear!,” they called on Elisha Cook, Jr. He spent his career playing boyish sadists and doomed patsies, his eyes flicking back and forth above a newspaper like shadows of tennis. As Wilmer the “gunsel” (a gangster’s bodyguard and sometimes lover) in The Maltese Falcon, he got betrayed by his own master at Humphrey Bogart’s idle suggestion. When Cook appears in 1973’s Messiah of Evil, his role seems familiar at first: the town drunk, telling stories from childhood for wine. Then he starts rambling about the “blood moon” and “children eating raw meat,” a mystic resigned to conveying the universe’s malice. Elisha Cook rarely survived long enough to read his name in the credits, but here he gets slaughtered by the very next scene, which may be a personal record.

Messiah of Evil was directed by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, a couple unfortunately better known for Howard the Duck. That disastrous George Lucas gig followed their scripts for Temple of Doom and American Graffiti; like seemingly dozens of other people, they also did uncredited work on the Star Wars screenplay. (Brian De Palma felt compelled to revise his friend George’s opening crawl.) As Huyck explained it decades later, a producer offered some money for their own movie midway through American Graffiti, with one demand: Do you have a horror film? They said: “No, but give us two weeks and we’ll come up with something.”

By chance or by design, Messiah of Evil only suggests a plot. A woman named Arletty visits the coastal California town Point Dune to see her painter father, finding his house abandoned and empty except for a paranoid diary. She falls in with a trio of post-hippie hedonists, whose leader Thom variously calls himself a Portuguese aristocrat and a “collector of tales.” Undead creatures begin to gather on the beach, staring up at the moon. Locals speak of a dark stranger long awaited. Motivations remain obscure. Nobody bothers to explain whether these monsters are zombies, vampires or ghouls—for five or ten minutes at a time, there’s hardly any dialogue at all. To the sleepwalker, not even death feels urgent. Messiah of Evil has a climate familiar from dreams, a languor of violent colours. “It’s like everyone was on Quaaludes,” Willard Huyck said in a documentary short, “when in reality we were on methamphetamines.”

There’s something autumnal about so many horror movies: The croak of leaves underfoot, the chill that never reduces to ice. Messiah of Evil is summery. The sky behind the beach looks swollen with humidity, overcast, featureless. Crimsons and purples saturate everything. When Arletty’s father finally succumbs to that evil influence (“I’ve already tasted human flesh!”), he smears blue paint all over his face, like Jean-Paul Belmondo preparing to blow himself up at the end of Pierrot le fou. Barely out of film school then, Huyck and Katz have joked that their process involved “pretentious homages,” and the techniques they used—overlapping voiceovers, performed alienation, a denial of closure—feast on the common blood of Hollywood vampires and European art cinema. Elisha Cook, Jr. was happy for the work but a little bemused: “This is so strange,” he said during shooting, “the first time in my career a director’s told me to look directly into the camera.”

The history of that film-school-to-B-movies pipeline is told too often as a creation myth, with the new pantheon—Jonathan Demme, James Cameron, and Francis Ford Coppola all received early gigs from exploitation filmmaker Roger Corman—reshaping the wreckage of the old studio system like Tiamat’s corpse. But godhood is boring. Because Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz have never enjoyed such prestige, Messiah of Evil frustrates attempts to elevate or ascribe it, to claim it for one facet of an auteur’s lengthy filmography. The cast was made up of friends, TV guest stars, actors from 1950s Westerns. Joy Bang, one of Thom’s female companions, quit the business afterwards and went to nursing school. (Thom was played by Michael Greer, shunned mostly to bit parts and stage work for being openly gay; his impassive charisma only deepens the movie’s mystery.) Watching these faces in Messiah of Evil, there’s a sense of estrangement, as if tracing events back to some half-remembered nightmare.

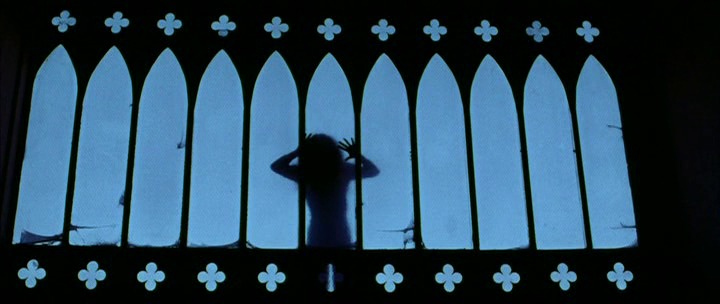

The film’s most prolific alumnus is actually its production designer Jack Fisk, a favourite of David Lynch and Terrence Malick (he’s been married to Sissy Spacek for forty years, after they met working on the latter director’s Badlands). You can see why Lynch likes him. Fisk filled Arletty’s father’s house with pop-art murals that lure and mislead the eye: Grey men in black suits, dressed for somebody’s funeral. A bed dangles from the ceiling on chains; ornate windows embellish the light. The isometric lines of fake Ed Ruscha paintings isolate characters beneath them. This house implies no continuity—trying to figure out its floor plan is unnerving too. Messiah of Evil doesn’t scare with monsters (looking closely, half of the ghouls seem to be unimposing senior citizens). It shows how horror can annex a place instead, compelling you to pass through familiar and traumatic rooms. That gathering dread as your heel meets the floor.

In his monumental film essay Los Angeles Plays Itself, about Hollywood’s capture and erasure of the city, Thom Andersen singles out Messiah of Evil for lingering on temporary spaces like motels and supermarkets. The directors were thinking of a Norman Mailer line from the time: “If a catastrophe ever destroys the world, it will all be rebuilt to look like the San Fernando Valley.” Gloria Katz has also said that she had Antonioni’s work in mind—actors made scarce by the landscape. The effect is both sublime and disturbing. When one character wanders through the closest grocery store, they shoot it as a temple of pale blue glass, so beguiling that she only belatedly notices the customers devouring raw meat. During an early, creepy scene, Arletty stops at a gas station and finds the attendant unloading a pistol into the darkness. He walks back over, fidgeting with a rag. “Fill ‘er up?” In the distance a howling can be heard.

Horrors lying just beneath the loose skein of everyday life is the constant theme in H.P. Lovecraft’s stories, an inheritance passed down to Messiah of Evil. Unlike that sour tendril-lover, Huyck and Katz were aware of everyday life. The emotionless performers cling to each other with desiccated appetites—in California, not even Lovecraft can stay Puritan. (A Luc Sante essay once listed all the things that frightened H.P.: “Invertebrates, marine life in general, temperatures below freezing, fat people, people of other races, race-mixing, slums, percussion instruments, caves, cellars, old age, great expanses of time…”) And the “dark stranger” in Messiah of Evil is no votary for unfathomable alien gods; he’s a prospector and preacher, a very American cannibal. To the people of Point Dune he was never really a stranger at all.

Providence drove the pioneers to seize California, but public money built the railroads and dams that made it fertile for exploitation. Joan Didion described the state’s rulers as “subsidized monopolies,” with agricultural giants succeeded by defense contractors (a rather bloodless way to describe artisans of the missile). I’ve been thinking about another line from that Messiah of Evil documentary: “The picture was made during a huge lull in the aerospace industry, so a lot of the extras in the movie are unemployed workers that we found.” The apocalypse decided that you’re surplus to requirements, but we do have temp work available as a herald. Some hideous thing washes up with the tides, and everybody on the beach screams, unable to recognize the monster they submerged.