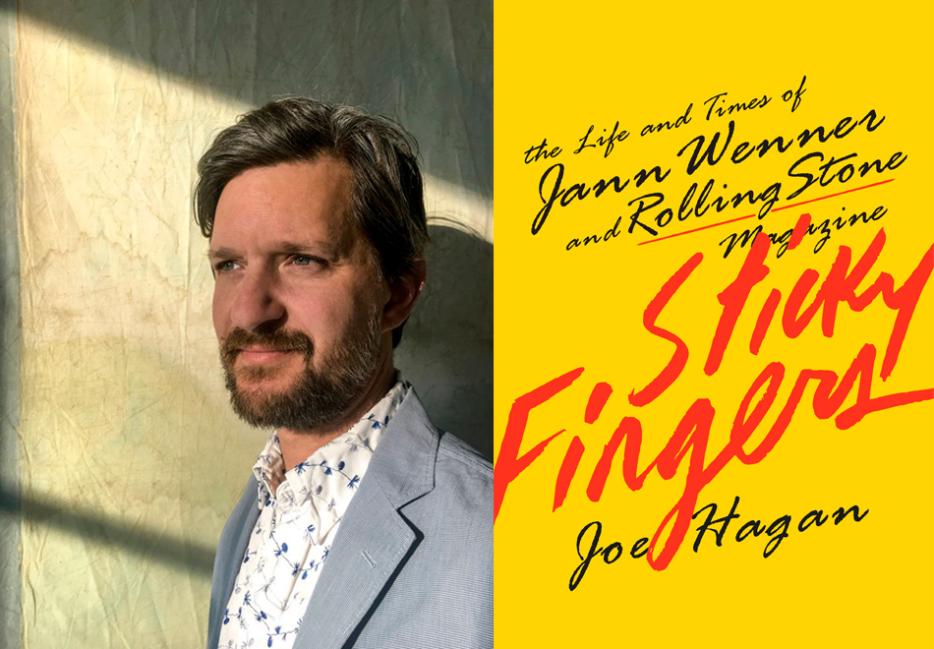

For several generations, an image of rebellion captured in a stuffy office above a printing press on a street in San Francisco has echoed through youth culture: to be embodied, rejected, imitated, trashed, and capitalized on. That image was crafted by Jann Wenner, and the magazine he founded in the late Sixties: Rolling Stone. In Sticky Fingers (Knopf Canada), the first biography of the editor and publisher, journalist Joe Hagan, much to Wenner’s recent and very public chagrin, traces its subject’s journey from a family history of arson and neglect to hiding in a closet on acid to throwing himself into the counterculture, packaging it, printing it, and selling it. Wenner captured the rock and roll scene and presented it on his pages as a blueprint for a new world—and a new customer base.

In his biography, Hagan paints two sides of Wenner: a fanboy gone wild, obsessed by fame and money, and a closeted man who would chant Beatles lyrics like a battle cry and pump his fists at staff meetings; someone channeling passion in the only socially acceptable way he’d been offered (what is talking about music, anyway, if not a way of talking about arousal, excitement?) and collecting charismatic friends, contributors and cover stars like charms on a bracelet. The book sheds a revealing light on Wenner, but also some of his most famous collaborators, from Hunter Thompson to Annie Leibowitz and Mick Jagger. It traces the rise and fall of the magazine—at times clutched tightly in Wenner’s coked-up grip, and at others chugging along with barely a glance from its editor, who was busy on his private jet—and the good and bad therein, from the female founding of Rolling Stone’s first fact checking department to Thompson’s homophobia. But always, Wenner comes across as a man with a unique ability to pin culture to butterfly board, someone whose enthusiasm is wielded as both a tool and a weapon and whose obsession with celebrity culminated in his purchase and revitalization of US Weekly.

It’s a book of tensions: between fandom and journalistic integrity, between financing and rebellion, between personality and projection. And it’s as much a story of the modern media landscape as it is the story of Wenner’s life.

Haley Cullingham: So, you’re all over North America for the next few weeks.

Joe Hagan: Yeah, it starts in Brooklyn, and then to seven cities altogether. It’s a lot, and exciting, and nerve-wracking. In the background, you have the subject displeased with the book.

In your afterword, you wrote that you saw that coming, potentially. I wonder if there’s a part of you that feels like Wenner being mad means you did your job?

I don’t exactly make that leap. A lot of people have, and I appreciate them making that leap. It’s not like I measure how good my job has been done by how mad he is, but I did know going into this that the possibility was very high that he wasn’t going to like a true story. And that’s just from knowing him and talking to him. Listen, he invented his own reality through the Rolling Stone magazine. He printed what the reality was going to be, and he’s used to having the control. And to his credit, he let go on this, which he hadn’t done before. But he also knew that he didn’t have a lot of options. He had two other books go down the toilet, and the fifty-year anniversary was coming up, there were only like four years to go, and he knew that if this was ever going to happen—which he wanted it to, clearly—he had to pull the trigger. And that put me in a situation where I could demand independence, and I knew I had to have it, because I’d been a journalist for seventeen years, I wasn’t gonna throw that away on an authorized biography. And that’s how it got started.

What were your touchstones as you were working on it? Were there other biographies you were looking to?

Yeah, sure. I remember the one that I thought about a lot was the David Hajdu book, Positively Fourth Street, which is the story of Dylan, Joan Baez, Richard and Mimi Fariña. She was a musician, he was a writer, and they were four friends in the mid-Sixties, and it’s all set in the village in New York City, and it’s really beautiful, tightly reported, in a very short little period, about these four people’s lives. And Bob Dylan kind of comes out as this conniving, ambitious guy who rides Joan Baez’s fame to his own fame and casts her aside. But in the middle of that, all of this wonderful culture is bubbling around them and you learn all about the world that they were in. And I wanted to get some of that in my book.

The other book that was a huge influence on me was Peter Guralnick’s two-part biography of Elvis Presley, which is magnificent, one of the great biographies of all time. So detailed, and granular, in how it goes through the life, that by the time you get to the end, you’re crying when he’s gonna be dead, you just can’t believe it, you’ve been with this guy for that long, you’ve been on this ride for two giant books. So I loved the impact of that.

And then of course to keep the tone that I wanted, Joan Didion and Eve Babitz were very strong voices for me. I really read a lot of them to keep my own voice in—first of all, they wrote about the period I was writing about, Sixties and Seventies, and they had a real great feel for it, and they were a little bit not writing about it in the same way everybody was writing about it. They had a little bit of outsider point of view, but they were in the tradition of Raymond Chandler and the noir style in that it was dry but with a little bit of an ironic undertone to it, and I loved that. I really was getting a lot out of reading Raymond Chandler, Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, to get a feel for the Seventies, and I used to joke at the outset of this book, “I’m going to make this the War and Peace of the Seventies.” But I just wanted it to be that rich. But also, kind of looking at it with a little bit of a—[he side-eyes]—‘cuz that’s what they do and I love that vibe.

You’ve mentioned Tom Wolfe in interviews about the book. Did he have an influence on the tone, too?

A little bit. That’s sort of baked into my style, and the reason is that I used to work at a newspaper called the New York Observer, which was very influenced by Tom Wolfe. The editor made everybody sound like Tom Wolfe. There were a lot of exclamation points. And lots of new journalism techniques thrown in—I try to carve those back because they’re embarrassing if you overuse them. So occasionally I would have little touchstones to Wolfe, for sure. I used to sit next to his daughter at the New York Observer, I used to call him up if I wanted a quote about some subject that I knew he knew about. One of the rockets with some people in it blew up at one point and I’d call him to talk about the space program, and he was always really generous and fun. But, you know there’s what they call the anxiety of influence? He’s one of those people I’m anxious about not being too influenced by, because you don’t want to become an imitator.

One of the threads that really fascinated me throughout the book was how you set up this idea of Jann Wenner and his influence on what media looks like now. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that, and also talk about whether you see him as an architect of that, or if he was just going with a flow that was inevitable?

I did begin to think of him as an architect of modern celebrity and media culture. The two biggest magazines, the two most successful magazines in the 1970s, were Rolling Stone and People. And if you think about it, so much of what we end up seeing in the culture has its roots in that kind of magazine making. It’s about getting personal with celebrities. Because Rolling Stone was promising, “You know that old, kind of controlled celebrity that was phony? We’re going to rip all that away. They’re not even going to have their clothes on, and they’re just gonna be talking for like five pages.” Now listen, there was the Rolling Stone interview, the Playboy interview before that, and [Wenner’s] interview was an homage to that. But the rock and roll world, the youth boom, was built on this version of celebrity, and Jann was instrumental in that, and so was Annie Leibowitz. She was an instrument of his magazine making and of his reinvention of celebrity as a, if you want to be cool, and hip, and down with the kids, this is what your celebrity has to look like.

Well, now, flash forward these many years, the internet catalyzed a lot of this. I wrote an article about Twitter a while back and the poohbahs at Twitter were like, “You have to be authentic. That’s your thing. If people believe that’s you on that Twitter feed, the more successful it will be. The more you can pull away all the mediation.” And that’s the whole idea of Twitter. You can connect directly without any interference. “And this is me.” Well, of course, it’s malarkey, because you’re inventing your authentic self. Well, that’s what Jann was doing with these rock stars back in the day.

And with himself, a little bit.

And with himself. To take it a step further, and people can debate this, but my contention in this book is that [Wenner shaped] the kind of supersizing of celebrity and fame, especially after the internet catalyzed everything and then US Weekly came along, which was very much a part of that, and kind of re-reinvented even more stripping away of the artifice, or at least it looked like that. And that’s from the reality TV age. US Weekly was sort of paralleling the rise of reality television.

When I was writing the end of this book, it was during the election, and I remember thinking, how does Trump being elected fit into this? In the book that Jann would have written, it would have been just completely natural that Hillary would be it, because then it would be the victory of the liberal baby boomers that came out of the Sixties. Well here it is, another baby boomer, same age as Jann, but he’s this fame monster who just loves attention and he’s turned the entire media into his, because nobody can look away, it’s like this giant car wreck everybody’s watching. And at some point, it occurred to me, this was the inevitable result of celebrity culture taking over the world, and decoupling from ideas. From even values of any kind. And that the ultimate value just becomes attention. And then you get him.

I’m not saying Jann’s responsible for him, in any way. They’re similar guys. Similar creatures, let’s put it that way, just narcissists of a sort. But there is a line to be drawn there. And I didn’t want to hit it too hard, but I wanted people to understand. At the end, I say, it’s a story that begins with John Lennon and ends with Donald Trump.

Did that thread emerge as you were researching?

It came at the end. I knew there was going to be something about celebrity and the age of narcissism, that was a thing I always was thinking about. But this sort of just proved it. It was this giant thing in front of me, and then all these people who knew Jann, friends of his, just were coming out of the woodwork to call me and say, “You know, when I see [Trump], I just think about Jann. Jann acts like that. He says things like that.” And there was a moment where I was like, I guess I’ve gotta write that. He’s not gonna like that. But the truth is the truth, I can’t avoid the narrative that I’m being handed on a platter by everyone who knows him.

Something else that you capture really well in the book is the way that the Baby Boomers sold out, and compromised their values. And Jann says it himself in the book. The John Lennon to Donald Trump comparison does feel like the perfect example of that.

Well, listen, I’m not the first person to say the Baby Boomers are narcissists, but Jann was always the avatar of that for a lot of people. And in a way, the whole reason the book homes in on all these ego clashes is because I wanted to strip away the idea that one person’s good, one person’s bad. I wanted them all to just be a bunch of assholes fighting, which they are, and I didn’t have to make it up. It just was what they were. And when they weren’t doing that, they were holding mirrors up to each other to glorify who they were. And some of these people are artists who I love. I love the music. But I don’t think it’s a huge leap to see that cutting cocaine off of mirrors was a thing. This was the “Me” Decade. A line that occurred to me towards the end of the book was that after the “Me” Decade, it was just more “Me” Decades. And then another “Me” Decade, and the “Me” Decades just continued until you have President “Me.”

In the book, you say the Seventies were defined by Rolling Stone, and then the Eighties were defined by MTV. What’s defining that now?

What defines it now is social media. Somebody asked me, “What’s the equivalent to Rolling Stone magazine today?” Well the equivalent of Rolling Stone magazine today is your Facebook page. You’re on the cover of your own Rolling Stone—everybody is. And everybody is telegraphing to everybody else, here’s me on the cover of my own personalRolling Stone, and here’s my confession. And here’s me on vacation, here’s me being authentic—everybody’s doing it. So instead of a vertical, where you have Rolling Stone at the top [in] a gatekeeping role, deciding who’s going to be in the spotlight, it’s just a horizontal—it’s been flattened. The world is flat, as Thomas Friedman said. And it’s true across the culture.

It’s funny that Jann, who feels like someone who’s such an embodiment of that, didn’t adjust to it. And I guess that’s about control.

He was repelled by it, as soon as he saw what it was gonna be. In the conversation he has with Mick Jagger [about the early days of the internet] there’s that thing about Jagger saying, “Oh, I go and get the gossip from these newsrooms,” and Jann’s like, “You mean, anybody can just go in there and do that? That’s not good!” And then you realize he knew right away, he just had a sense that this is going to be not for him.

Last night I was looking through the oral history of MTV to see what people say about Rolling Stone, and something that I found really funny is that almost every reference is about Rolling Stone calling out MTV for being too sexual. And Rolling Stone criticized them for being paid to mention Michael Jackson as the King of Pop four times a day or something, but Rolling Stone was doing similar things in the Seventies.

Oh, absolutely. And then flash forward to the Nineties, and all the clothes came off again. All the covers in the Nineties, just endless shirtless people, naked Chili Peppers with socks on their cocks. I touch on that in the book, because [Jann is] sort of like, “This is so tawdry” [about MTV], and it’s like, “What?” But Jann had turned a corner into being part of the go-go, Baby Boomer, I want to be legit. And these kids, “What is this music? I don’t get this.” You know?

I grew up with MTV. I’m from that generation. I remember the first video I saw: “I Want a New Drug” by Huey Lewis and the News. And that’s when I was a full-on MTV kid. It raised me, basically, and taught me everything I know about culture. And it was somewhat different from the Rolling Stone world. But I subscribed to Rolling Stone as a kid. They would publish these late Hunter Thompson pieces, and I remember just being like, “What is this guy on about?” I did not know what they were talking about. Later on, I would read Fear and Loathing: “That’s really funny. What an amazing piece of work.” But he burned out after like three years. And then the rest of his life was a big parody of himself. It went on and on. And I knew I had to bring that out too, and reveal him as this gross, tragic guy.

And the timeline feels so stark in the book.

It’s so fast, because of the drugs. He just went so crazy with the drugs. And listen, you’re talking about a generation that thought just throwing off the rules and embracing all the libertine behaviours was going to be the answer. And the Seventies were sort of the big cautionary tale. Then everybody’s just going to go off the rails. And they did. While doing a bunch of rails. And that’s why the late-Seventies period was so interesting and tawdry and horrible, because that’s when everybody’s just gross. But you had to get that, because that’s sort of the decadent moment and that’s what made Reagan possible. I really believe that. You can kind of see it—it’s how the pendulum swings in life. At that point people had seen enough. And some of it was racist and anti-gay backlash. But in Jann’s case, he was just living with this jet-set crowd that were not really even doing anything politically.

Do you see him as the first person who capitalized on commercializing nostalgia?

I think he was a pioneer in that for sure. And he understood that very quickly. Even by the early Seventies, they were already doing lookbacks on the Summer of Love. And it became a joke. For the ten-year anniversary of the birth of Haight-Ashbury they did a big thing—this is in the mid-Seventies. Jann has always had a really sharp understanding of anniversaries and the power of anniversaries. And every time there was one, he would make a big tent-pole event. He knew. That’s how you re-stamp the brand: bring this big powerful anniversary around. And anniversaries have always been a thing for him. Look, he wanted me to do this book in time for the fiftieth anniversary. And he always understood that. And around the times of the anniversaries, especially after the Eighties, he would do the anniversary and then see, “Anybody wanna buy this magazine? Let’s see what it’s worth.” He was always trying to measure the value.

Were there any old pieces from the magazine that you read in your research that really blew you away?

Yeah, a lot of stuff. Eve Babitz wrote a piece that was published in the early Seventies, about going to Hollywood High, and the whole essence of growing up in LA, and the Hollywood scene, and the kids all being really handsome and liberated and it’s just a wonderful essay. I talk about it in the book.

Cameron Crowe wrote some great pieces. He wrote a great profile of Fleetwood Mac that was wonderful because it was around the time that everybody knew that Fleetwood Mac had all kinds of interlocking relationships that were screwy, so he decides he’s going to just write the profile as four separate profiles of the four group members, and see where they were in their little world and what they would say about the others, and the bass player’s living on a sailboat in LA harbor and all these funny scenes, it’s just a real feel for the times. And his interview with Joni Mitchell was amazing.

And you know, the Hunter Thompson stuff, some of it was very good. The Fear and Loathing stuff is really funny. I could probably go on. Those are highlights. And I liked some other things I’d read in Rolling Stone over the years, in later years.

Speaking of the later years, I wanted to talk about the University of Virginia piece that Rolling Stone published in 2014 that was later discredited, “A Rape on Campus.” To me, in the book, it felt like Rolling Stone and Jann had always strategically used good journalism as a way to poke, like, “Remember we can do this when we want to, and then we’ll win a National Magazine Award, and you shouldn’t underestimate us.” And the Virginia thing was the inverse of that. And it obviously got away from them so quickly. I wanted to know if you interviewed the fact checking department?

No. I interviewed all the editors and the lawyers. My thing was, I made a decision that I was not going to use my book to do a post-mortem on UVA. I wanted to build some context around it, but I didn’t want to do the Warren Commission on UVA, it had already been done by [the Columbia Journalism Review]. And my feeling was, these people have suffered enough, and I knew some of these people, and they were very, very traumatized by this whole experience, as you can imagine.

My assignment here was to follow Jann. What’s happening with Jann? I’m thinking, what can I bring new to it, to this story, that hasn’t been told? And I realized, well, what I can do is bring some context to, where were they in the run-up to this? What was going on? The lawyer cashing out right at that moment, and this other lawyer coming in, and all these weird things were going on, and Jann was saying, “No more of these soft features, we’re going to throw this other one out, so do that.” So, they’re like, oh shit, okay, get that story on board.

Because I did see that there was a sense of some of the looseness around that story, I think that partly had to do with how the organization of Rolling Stone was shrinking. And the financial situation, and the desperation for hitting it big was important to Jann. That quote, which I imagine must be painful for him to read, when he’s like, “We’re doing it now, we whacked a hornet’s nest on this UVA thing. Nobody watches Saturday Night Live.” And I remember looking at that quote in my notes and going, I gotta use that. Because that’s just exactly what this is about, you know what I mean? He wants to be in the conversation. But they’re at a point where the magazine—they just blew it, man. I mean, it was so bad. I mean, the fact that they didn’t call anybody… The thing was, they named the frat. Nobody would have known if they have never named the frat. But they decided to name the frat, and that exposed them. I’m not saying they should have got away with putting some sort of fictional thing in there, but like, if you’re gonna go at somebody with something that shocking and that horrible? So dumb. It’s head-shaking. Out of the wood work, everybody was calling me from theRolling Stone alumni network saying, “I just can’t understand why the hell that happened.” But anyway.

And Jann seemed to absorb it slowly. It took a while for it to dawn on him, how bad it was. “Do you think,” I asked him towards the end, “that the UVA thing damaged your reputation?” “No.” I was just like, you are delusional. I mean, I felt bad for him, and maybe it’s just hard for him to accept. And he’s gotten by a lot in life by having delusional visions of what’s going on, and sometimes that’s the by-product of people who are really talented and successful, but in this case, it was just sad.

I wonder if this comes down, too, to him not understanding internet culture. It’s a lot easier to re-invent yourself in 1975 than it is now.

Yeah, totally. The thing is, they didn’t even start until three or four years ago to really think about ramping it up on the internet, you know? They started to look at Vice as the model. But the thing that Vice has is not only does it have an authentic connection to youth culture, and real energetic, lively content, the founder of it got huge capital inputs from Rupert Murdoch and this guy that ran Viacom, Tom Freston. Rolling Stone, I think that’s what they’re looking for right now. They need somebody to come in and fund this thing, and help it steer over into this more multimedia thing. But it’s very hard to do that if you just have a website, and a very thin magazine. They need money. The question is, are the people with money going to come along and have the same idea that they have about it? And are they gonna want Jann and his son hanging around while they reinvent this brand? Maybe they’ll let them hang out for like six months, but I don’t see that. At the same time, I don’t see what Rolling Stone is without Jann. There’s a level at which it’s just a brand. And who is it a brand for? People thirty-five and over, basically. It does not resonate with twenty-year-olds, I don’t think. I could be wrong, but I don’t see it as a jazzy brand for the millennials and younger crowd.

Even people my age, I’m in my early thirties, we were raised on the nostalgia for Rolling Stone, that’s the context we grew up with, but now we’re in that older demographic.

Yeah, so we’ll see. I hope something great happens to it. I’m skeptical. But I don’t wish ill on Rolling Stone or Jann Wenner. I’m not sure how I could have been more devoted to him than writing a 500-page book about him. He may not like what it says, but I was committed to his story. I feel like if nothing else, that’s evident.

Having spent so much time with him, and thinking about him, do you think that his legacy has been written? Do you think this is how we’re going to remember Jann Wenner, or do you think there’s more to come?

This is it. There’s no more. It’s the end of the story. There might be some little blip here or there, but he’s not going to reinvent himself. He’s going to retire. And he had these health scares this summer—he had a heart attack, he broke his hip. He had a triple bypass operation and a hip replacement. He’s walking around with a cane and he’s a shrunken man. And that’s partly why he’s probably so upset right now, he’s having a hard time all around. I’m sympathetic to that. I didn’t write the book from the point of view of feeling sorry for him, though. If he was in a stronger state in his life, maybe he would have been able to swallow this book more. Or he would come at me even harder and try to kill me. [Laughs]

But, this is his legacy. I think it’s a powerful legacy for him, this book. It doesn’t have to make him a good guy. Steve Jobs was a terrible person. Somebody just told me the other day that if he had lived to read Walter Isaacson’s book, he would have been infuriated. Which I thought was an interesting thing. It was somebody that knows them, knows Isaacson. Because the family was infuriated. And I get it but, you know, that was him. Walter Isaacson is a great journalist. These things happen. Writing a biography of a living person is a real rough ride, man. It’s a rough ride.

Do you think you’ll ever do it again?

No. No I will not do it again. Let’s just say, I can’t imagine at this moment ever wanting to do it again. Because it was really stressful and very hard. But I did my best, so that’s all I can do.

Is there a part of the book that you find especially fascinating?

The part that got me the most excited, the whole middle section of the Seventies, I just had so much fun writing it. I was really into Jane [Wenner, Jann’s ex-wife] and I was really into the Sandy Bull drama, and suddenly then there’s Max Palevsky, and all these characters start coming in. I just loved all these characters. I loved Earl McGrath and his Italian countess wife and the jet-setters. I loved all that stuff.

And the late Seventies decline of all the characters was really intense to write. Just, you know, I gotta write this. I can’t just shrink from this stuff, I gotta put it out there. And then discovering, I remember, it was a revelation to me, discovering that his introduction to that book of photos that I excerpt in the book, I read that and I was like, Oh my god. He gave it up, man. He’s just like, we’re here to be rich, and famous, and have fun. That’s the point. And you were like, that is the end of the Seventies, man. That’s the end. That’s the end of the line. That’s why, when you get the death of Lennon, it’s such a reformatting moment. And I loved how cleanly the story just arrived to this doorstep, and then you could cut it off and start the next chapter.

I do remember thinking, ugh, gotta write the rest of this book, the Eighties and the Nineties, and it’s just not gonna be fun for me, I thought. But as I got into it, I really started to have fun with that part too, because I realized, now it’s gossipy. Here’s one thing I remember—this is interesting, actually. I remember being really disappointed that I would bring up the Eighties and Nineties, “What were you listening to? What was the music, what were the articles you remember?” [Jann] would kind of remember a few articles, the Tom Wolfe, he was proud of that—he was not that focused on the culture anymore. What got him excited, what I watched him animate and go on and on and on in beautiful soliloquies about, was the private jet. He loved that private jet. He just loved it. It was like the greatest thing that ever happened to him, practically. He just could not have been happier than when he had the private jet. Because it just signified that he was literally at the top. And he just loved it. And at one point, I remember, when he first told me all that stuff, I was like, “I’m not putting that in the book, just so lame.” But then I thought, no it’s not, it’s exactly what the point is. That’s what this was all about. I need to say as much as I can about this plane, because that’s what he cares about. And so that turned out to be a thing that I could flesh out and turn into, this is what the culture was about. This is what he was about. The motorcycles, and being on a plane. When he says, “I used to just fly it around LaGuardia during lunch,” and I just thought, that’s so cute and ridiculous.

There’s a childlike aspect to Jann. I describe him often as Peter Pan and Captain Hook in the same man. I was worried a little bit: is this book capturing enough of his ebullient innocence at the same time that it’s capturing his shrewd Captain Hook side? But I couldn’t really worry about it, I just had to write what I knew and write what I saw.

And then the Nineties, the coming out, I knew was going to be a big thing. Talk about a soap opera. That was really intense. I remember, when I arrived to that last line, I knew Jane had to have the last word. You know those quotes, “I just felt bad for Jann, he had to be in the closet, but I think he still loved me, don’t you?” It wasn’t the first time she asked me. She asked me many times. It’s heartbreaking. You poor woman. It’s sort of sad. At the end, they wouldn’t get divorced for seventeen years because she’s in such denial about it. And you’re like, wow man, that is just so powerful. And I wanted to put that on Jann. There’s that Bette Midler quote where she’s like, “I don’t care if he never wants to be my friend again, that’s fucked up and he doesn’t face that.” I was like, well, he’s gonna face it in this book.

In a weird way, as a biographer, you’re sort of in the middle of this. It’s not like clean separation from his life and your life. You’re in there mediating, almost like some kind of storyteller therapist who’s going to lay out their life in a way that they’re not prepared to have it laid out all the time. And that’s why he’s probably upset right now and I get it.

I wanted to ask you about interviewing Jane, because she’s such a compelling character in the story. This is in the book, but can you talk about how you see her influence on Rolling Stone?

There’s two ways that I see her as being part of the formula of Rolling Stone, or three. One is that she managed Jann. He was a wild man, like a pinball flying all over the place, and she gave him a secure world to inhabit. She also managed the talent. As I explain in the book, Hunter Thompson, Annie Leibowitz, these people were very attracted to her, Max Palevsky, an investor, moneybags. These people were into her, more than Jann. And so she kept their social world intact. That was huge, because part of being a magazine editor and publisher was navigating and forging into these worlds and bringing these people into their orbit and then transacting them. And she was a part of those transactions. The Paul Simon story, which is incredibly weird and amazing—she leads him on, it seems like, for the purposes of keeping him in their social orbit and putting him in the magazine. When Annie Leibowitz said that, it blew my mind. “That’s what she did.” It’s pretty intense. But, you know, they were a team.

Thethird thing, and very important, was that she was the muse for Annie. And that it was her sexuality, and her beauty, that was almost a life model for Annie. She saw her, and that sexuality of Jane is sort of replicated in all of these people that she was photographing. If you see the pursed lips of Linda Ronstadt, or whatever, you could find a picture just like it of Jane that she took before that many, many times. And you know, [Leibowitz] talked about that. She said, taking pictures of Jann and Jane, especially Jane, who she was in love with, informed how she saw people and took pictures. And I thought, well, that’s huge. Because Annie’s entire career was forged at Rolling Stone and this is how it came to pass.

I’m curious about what music journalism you read now.

I read quite a bit for this book, and I wasn’t impressed with much of it, frankly. There are certain people who are just fantastic. Peter Guralnick is a fantastic writer. I loved the David Hadju stuff, he has another book called Lush Life about Billy Strayhorn who was the gay songwriter and arranger for Duke Ellington, he wrote some of the most famous songs that had Duke’s name on ‘em. Great book. Modern stuff, I read the New York Times Arts section, but it feels like everybody can write about music now, because everybody has a personal relationship to music. I’ll tell you where some good music writing is, in Oxford American. That’s a great magazine. They publish some fantastic music journalism. If I were to say my favourite stuff, it’s always in there. Mainly ‘cuz those are the artists I’m interested in. People off the beaten path, soul people, blues people, old jazzers. I’m an old guy so I like that stuff. I love reading those deep histories.

I’ve done a lot of music journalism, and a lot of music writing. It’s hard to do. It’s not as easy as everybody thinks. Everybody’s got an opinion, but writing about musicians, the famous, “it’s like dancing about architecture.” There’s some truth to that. It’s hard to capture the essence of somebody, and you’re not even hearing their music, and make it interesting for people. But occasionally you’ll run across something that’s just really brilliant.

I’ll tell you one of the last things I read that was a great piece, it was in the New Yorker, and it was about the history of people taping the Grateful Dead [by Nick Paumgarten], and it was this huge New Yorker article, and the guy’s a great writer anyway. He’s a good music writer, this guy. He doesn’t always write about music but when he does he does a great job. He wrote that profile of Billy Joel, it was about how Billy Joel just comes in on the weekends, does these big Madison Square Garden shows, and then goes back out to his retreat in Long Island and hangs out, and it was very funny, and it just gave you a feel. But listen, he’s writing about people where everybody already knows the music. It’s hard to write about people you’ve never heard of. I find it very hard to get excited about an article about an artist I’ve never heard. That’s a challenge.

Pitchfork, I don’t know, I can’t. I used to, all the time, I was a religious Pitchfork person ten years ago. But it may be that I just didn’t have time to do it while I was doing this book. And I read one great music book, I mention this in the Columbia Journalism Review thing, but The Lives of John Lennon, which is this book that everybody hates, it’s considered just a real scurrilous piece of trash, Kitty Kelly-level gossip thing. But it’s so well done, it is super compelling. If you read the first chapter, you’ll be like, “Oh my god.” It is outrageous, but it’s all true: John and Yoko living in the Dakota, in this isolated state, and being delivered heroin in a pizza box every day, they’re turning eccentric—it’s just really weird. I’m always looking around for something where you get excited, and you’re like, “Oh wow, this is real storytelling here.” I appreciate good storytellers.

I’m married to a novelist, and she’s twice the writer I am, she’s an amazing writer, and I learned a lot from her, because she really taught me about economy. And in this book, that was important, because this thing could have gone on for another 500 pages. So, I had to think about the economy of my sentences, and tightening things, which I got a lot from Joan Didion, who is the queen of economy. These little diamond sentences. I couldn’t get it down to the diamond. But she’s amazing. And I get more from those kinds of writers, writers that can cover anything, than I do from music writers specifically.