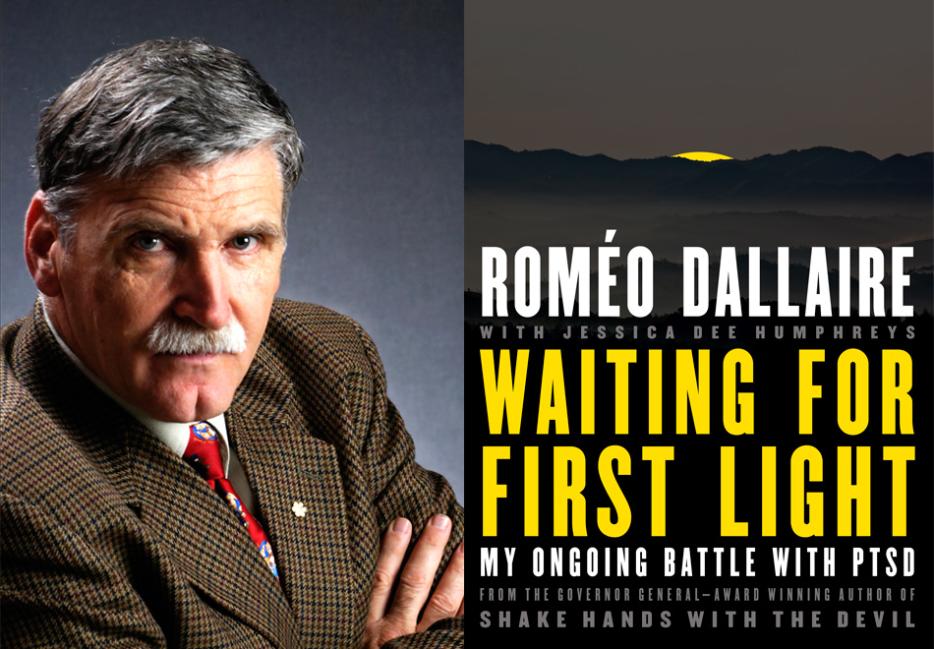

General Roméo Dallaire’s third book, Waiting for First Light: My Ongoing Struggle with PTSD, begins in 1994, when he returns to Canada after serving as lieutenant general representing the United Nations during a genocide that would see 800,000 Rwandans killed in just 100 days. When he arrived at the airport, there was no one from the military waiting to welcome him home.

Along with co-writer Jessica Dee Humphreys, Dallaire takes his reader through more than twenty years of suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The book recounts his harrowing attempts to reintegrate into life back in Canada, throwing himself into work and taking on ambitious posts within the military to put some distance, any distance, between himself and the genocide he was explicitly ordered not to interfere with. At times, he is comatose from alcohol or destroying his possessions in a drunken rage. In another instance, he takes out his father’s army shaving kit and slices his arms and legs with an old razor. We see him driving 150 kilometres an hour down a street with his children in the car. He is found drunk and passed out on a park bench in Hull one summer, which makes national news. Today, the former general is still recovering and now “retired”—he’s the founder of the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative, a senior fellow at the Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, travelling the world to consult on international conflict issues and writing another book. The morning that we meet, he has had no sleep, up all night staring out from his balcony at the city below after running into a former colleague who himself is suffering.

Katherine Laidlaw: You’ve written books before, most notably Shake Hands with the Devil, which won the Governor-General’s Award for Non-Fiction. But this book is incredibly personal, and deals with some weak moments in your life. What made you decide to do it?

Roméo Dallaire: There was pressure to get a biography out, from publishers who were getting pressured by other people, and individuals who wanted to write it—I absolutely refused to let that happen. And I liked the idea of not simply writing a chronological biography but having a purpose to it. PTSD seemed to be a backdrop for describing the reality of the last twenty years.

Early on, you talk about having dreams and those dreams weaving themselves into memories that come at you at different times. There’s one instance in which you’re at a farmer’s market in Quebec City after you’ve come home from Rwanda and something about the colours and smells triggers you and you run panicked to your car. In twenty years, have you ever had a reprieve from these kinds of episodes?

I think because of the medication, whenever I’m able to find non-stressful scenarios, that doesn’t occur. Last night I didn’t sleep because I knew something was going to bug me. I saw an old colleague who’s injured and spoke a lot about it with him last night in Kingston. What happens is, you’re vulnerable to scenarios that will lead you to that. That’s the difficulty, trying to build a prosthesis that might help when recurrences are triggered. That’s not an easy prosthesis to build. You need your therapy, you need the medication, and so on. But every now and again you get the feeling that somebody has stolen your prosthesis. And you’re left vulnerable to relive the consequences. It is terrifying in fact. You can actually see yourself doing things that you want to stop doing but you can’t.

Can you tell me about your different triggers?

When I was writing the first book, I brought a number of documents back with me. One of the books was made of the old writing-pad paper, real thick paper. I took it out and I was reading it pretty close to the table, my head bent forward. There was a bit of scent that was locked in there, and it took me weeks before I was able to get back to work. Scent is a very powerful trigger. It could be diesel burning that reminds you of when you were burning all the bodies. It could be a barbecue or something.

Do your doctors ever expect any of your symptoms to change?

I don’t know. Because what I’m doing is filling it with work. And at the same time, I’m screaming for time alone to be able to read. And reading is very difficult. I’ve become more and more aware of it. Reading is one of the greatest soporifics. Sometimes I really want to read something and I’ll fall asleep and I don’t even know I fell asleep. I remember one meeting in Uganda and we had two officers with us and we were having a conversation. I intervened with something that had absolutely nothing to do with the conversation and fell asleep during my intervention. It was the weirdest thing. You think you’re talking about the subject because you’ve heard them talking. Slowly that disappears and you don’t realize it but all of a sudden you’re asleep, in the middle of a sentence. They escorted me back to my room.

Do you think people have changed the way they talk about PTSD?

Jessica [Dee Humphreys, Dallaire’s co-writer] raised an interesting point, that there are more TV programs now that talk about it. Downton Abbey, You’re the Worst, Scandal. It seems like that’s normalizing the conversation. I think it’s gone beyond a flavour-of-the-month issue to something that’s more mainstream. It touches not only veterans but first responders. I hope the book gets to civilians.

The repetition of the word “injury” throughout the book is really important. I think a lot of people don’t think about it that way.

I think comparing it to a cancer is much better. Some become cured and others don’t. Many cancer patients, even though they’re in remission, have a sense of fatality that they never get rid of. My niece had leukemia and she beat it but she’s a changed person. She doesn’t have that same hard confidence that she used to have.

One of the most vivid parts of the book is one day in September, 1998, four years after you’ve returned from Rwanda, when you’re told by your superior, who is also a friend, that you have to take sick leave, which can be extremely detrimental in a military career trajectory. You describe waking up in Quebec City not knowing how you got there, and spending months in your pajamas, crying, living like a zombie as your wife and kids lived their lives around you. Do you wish you had taken a break from work earlier? Or do you think delving into work as deeply as you did was the only thing you could have done at the time?

There are only so many generals. So this is a bit different than in the case of lower ranks, where you’ve got more flexibility. But the job had to be done. There was so much to be done.

The perspective was, the more work you do, the better it was going to be because you’re going to forget faster. We really didn’t understand that this injury is not a stationary injury. It’s not like losing a finger and that’s it. You lost a finger but all of a sudden the hand starts to fall apart. Adding more pressure and stress on an injury that is based on an inability to handle stress and pressure, well that just continued to make it worse. Although my colleagues were trying to do the positive thing and continue my career, what ultimately essentially happened is that they just made the whole damn thing worse.

I may be living with the results of it, but it did permit me to do a lot of things to help others. This sounds really pretentious, to say you’re sacrificing yourself. I don’t want it to come out like that. But I was the right guy at the right time to do it.

If you’re going to live through those atrocities, to be able to make a number of positive changes after that seems like the best outcome.

It doesn’t attenuate though, what you lived, at all. But it at least eases the sense of guilt that you’re not just walking away from it.

In the book, you’re certainly critical of the government, military and the United Nations. The one instance that stood out most starkly to me was when you were in the Senate working on a sub-committee on veteran care. The vice-chair of your committee, a Conservative senator you’d worked really constructively with, got up on the floor the day you were presenting your recommendations and said exactly the opposite of what the two of you had planned. It seems that a lot of your life has been devoted to trying to make inroads that have been thwarted by bureaucracy or politics.

Obviously there’s a Don Quixote bent to my way of life. And I certainly don’t learn my lessons well. I think of all the times of those types of things happening, there was really only one where I would have punched out the person.

What was it?

I’m not going to tell you. But it was so flagrantly stupid. And you knew that people would suffer, and the individual was not even being sincere because he was just towing the party line. If he had believed in it and it was him, you’d say, well, the guy’s an idiot. But no, he was towing the party line with a fervour that was worthy of being crucified.

How do you cope with that frustration?

Well I can’t drink booze so I go back and work harder and harder. And spend a lot of time at night awake.

Do you not drink at all now?

I haven’t since my last suicide attempt, 14 years ago.

Congratulations.

No, I hate it.

Do you miss it?

Well, shit, everybody else is having a good time.