In 2014, as her mother was dying, Michelle Zauner didn’t make any art. This was unusual; as a kid, Zauner wrote fiction—”just little stories”—and learned to play music. She frequented open mic nights in Eugene, Oregon, where she grew up, and called her first solo project Little Girl, Big Spoon. After college, she fronted Little Big League, a low-fi emo rock band from Philly; Zauner sang about suburban malaise, disappointing relationships, and unfulfilling sex in a deceptively melodic, plaintive voice that she sometimes worked into a hoarse scream. She had just begun writing songs for a new solo project called Japanese Breakfast when she learned of her mother’s diagnosis, late stage intestinal cancer, in 2013.

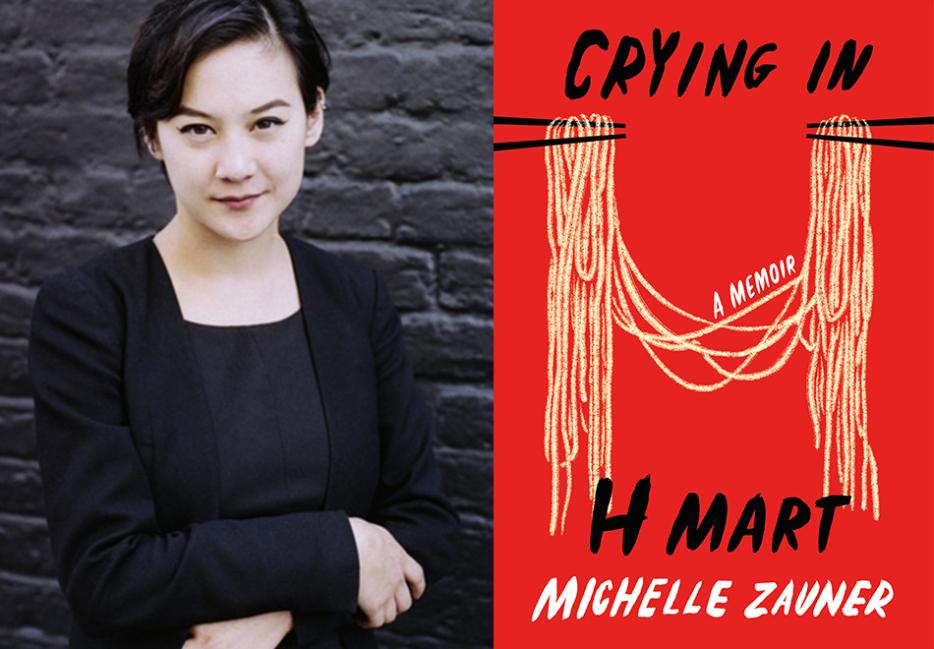

Crying in H Mart (Knopf), Zauner’s memoir about the months she spent caring for her mother before her death, is a confident exploration of the nuances of grief and a forthcoming account of an often graceless mother-daughter relationship. Zauner, who is Korean, recounts a fairly untroubled childhood: she tagged along with her mother on trips to Seoul to visit family; to the markets where they searched for their favorite Korean snacks and fare; to restaurants where they attempted to out-eat each other. Zauner’s songwriting skills prove impressively adaptable to memoir; the most pleasing sentences in the book are her heady and layered descriptions of these meals. Reading them might have been as gratifying as an actual meal, if the subsequent hunger wasn’t also a reminder of how bodiless mere words can be; a sentence, unfortunately, is not sundubu-jjigae.

When Zauner reached adolescence, an ineffable gulf opened between her and her mother. Her mother became controlling; Zauner began acting out. A series of increasingly painful confrontations resulted in Zauner moving out of the house. Later, she struggled to fulfill the role of caretaker to her ailing mother, how to sit with her grief and its disturbances. She toured with her band, planned a last-ditch trip to Seoul, and rushed a wedding to her husband Peter, experiences she now views as attempts to postpone dealing with her mother’s certain passing. Recounting this, Zauner affords herself no mercy; she writes honestly of her guilt, the selfishness of grief.

After her mother’s death, Zauner forged ahead with music. She recorded two albums as Japanese Breakfast, Psychopomp (2016) and Soft Sounds from Another Planet, both incisively personal works that include meditations on grief, loss, and the arbitrary but absolute nature of death. Japanese Breakfast’s third album, Jubilee, comes out this week. Aptly titled, Jubilee is a stark contrast to the band’s earlier works, and underscores Zauner's formidable range as a songwriter and musician. With Crying in H Mart, she proves she’s an assured artist who has accomplished a new form.

Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Naomi Huffman: How was the process of writing your memoir different from writing songs for an album?

Michelle Zauner: Two things were discipline and regimen. I told myself, it’s going to be crap. It’s going to be crap for a while. I decided I was going to write a thousand words every day. I feel like that’s an act of forgiveness in itself—like, it’s a thousand words every day, how could it possibly be good? It’s going to be complete, nonsensical garbage, and that’s OK.

Up until I turned in the final draft, I was truly devastated. I’d lost perspective; I felt as if I’d had this vision of myself, and I was three steps below the intellectual I want to be. I kept saying to myself, This is just who you are right now. This is an archive of your skill set at this moment. This is the best you can do right now. You spent five fucking years on this and you need to let it go. There’s a sad, cold, hard look you have to take of yourself as an artist—this is just who you are right now. You’re gonna get better.

Even though I’d never written a book, I had completed other larger creative projects. You know, I don’t love the first Little Big League record. I think I’m a much better singer, much better composer, and much better producer now than I was in my early twenties. I was twenty, twenty-one years old. But I’m still proud of what I made, and ultimately I’m not embarrassed by it. Art is just an archive of who you are at that time in your life.

How does the experience of releasing a book differ from that of an album or a song? Do you have the same anxieties?

With songs, it’s so vague! [Laughs] There’s so much to hide behind. People can interpret things in so many different ways, and it’s wild what people think some of my songs are about. I have this song called “Essentially” and there’s a line, “Love me asexually, love me like someone else’s wife.” And someone interpreted it as like, me wanting to have an affair, which is clearly not what that line is about at all. So I feel like, [with my music], I can’t get hurt, in a way, because there are so many different ways to interpret a song.

Whereas there’s nothing to hide behind in this book. If people misunderstand you, it’s your own fault. I was really nervous about this book coming out in a way that I’ve never felt about a record. It’s very naked. It’s me as a person, whereas in music, there’s a more fictional version of me that I’m presenting. But it’s also been really fulfilling in a way I never anticipated. The feedback I’ve received has been really beautiful and moving, in a way that I’ve gotten a taste of with music, but it’s deeper.

In the book, you describe feeling disgusted at your own impulse to write about your mother, to transform your grief and her suffering into a project. Having now completed the book, and seeing it celebrated, do you still feel some disgust?

I wanted to include that moment because it was a real, striking thought that I had. It was also a moment of taking a really critical look at myself. It’s honestly very hard to showcase your own flaws in memoir. It’s so important, and it’s so unfair not to do that to yourself when you’re doing it to other people in your life. I knew that these moments were something I had to find and expose—you know, what things was I at fault for? Because I was writing about things at fault in my father, my mother’s friends. It’s very hard! [Laughs] I never want to admit that I was wrong.

I think I was disgusted with myself because we were in the middle of it. You need to just be there. You need to not make it easier on yourself by making it into a project. I didn’t write or make any art for like nine months that year. It was a really foreign thing for me because that was all I knew, that was the only thing that gave me a sense of meaning and purpose. But in that place, in that moment, I was like, this is not the time for anything. You don’t get to have anything right now.

It was what I envied my mother’s friend Kay for so much. She completely gave up all sense of self to be a subservient caretaker. And I really struggled to do that, to be honest, and I had a lot of shame and guilt and regret about that. I don’t feel guilty about that now; most of my guilt was just that I knew I needed to spend every waking moment being there for my mom and not protecting myself with a project.

How do you trust your own memory?

That’s a good question. I think you have to accept that it’s never completely reliable. With any work, any document, memoir especially, it’s subjective. It’s going to be misremembered. I think you just have to try to present yourself critically, and the other people around you as generously as possible. A lot of that happens in revision.

Many songs on Japanese Breakfast’s previous albums deal with pain and grief, and Crying in H Mart is about learning from tremendous loss and suffering. But so much of Jubilee is about expressing and finding joy. Listening to it is relieving. Do you find it easier to make art from suffering? What was it like to write songs about joy?

I don’t think it’s easier to write about pain, but it grants a kind of self-seriousness, like this is a valid topic to write about, and I think I felt I needed that validation when I was younger. I felt I needed to prove myself, to prove I had endured enough to be a serious artist, and I don’t feel that way anymore.

I think it’s a natural impulse [to write about pain], it’s a salve to help temper it. Pain is a thing you get used to confiding about and navigating in art. It’s something I’ve done since I was a teenager writing about heartbreak and rejection.

One of my favorite songs off the record is “Kokomo, IN,” because there’s just no pain there at all. It is pure sweetness, and I loved it. It was easy. It was fun. It’s my favorite song on the album. Even writing it, there was no anguish. It came together very easily. It was a sweet story, and I didn’t think it needed any agony. I feel like I can do whatever I want now.

Are there other writers who tackle grief that you look to as guideposts?

There’s a type of grief in Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping—it happens in so many ways. Especially when you examine the siblings’ grief and how it impacts them. It makes me think of my father and I, how our grief affected us in such very different ways. There was this other type of grief that happened when we began separating from one another. Robinson explores grief in such nuanced and devastating ways.

I also returned to Cheryl Strayed’s Wild—I think because we have the same editor. And there are similarities [between our books], too. She’s this woman who seeks out an alternative form of therapy to help her through her mother’s death. I think you could write that book off as a Reese Witherspoon movie or whatever, but parts of that book are incredible—I mean, when she eats her mother’s ashes? That scene will haunt me forever. It’s really gross and intense, and so real.

I also really loved Shin Kyung-sook’s Please Look After Mom. She’s Korean, and it’s told from lots of different perspectives, and again there’s a kind of nuanced grieving that isn’t necessarily about loss.

Especially toward the end of her life, your relationship with your mother seems to change to become a true friendship. Was it important to you to portray it that way?

That was a heartbreaking part of that experience. I think it’s pretty common for adolescents to have pretty tumultuous relationships with their parents and then be able to return to them as adults as friends, or a type of friend. It was unfortunate that my relationship with my mother was turning a corner and I could see that a lot of the things I’d hated her for I was able to actually appreciate in this new way, with some distance. And I think she was able to appreciate me in this new way with some distance. I think our relationship would have been really wonderful. I so wish that my mom could be around for my thirties. It was important to me to show [her death] was so devastating in part because our relationship was getting to a beautiful new chapter.

There’s a line in the book where she says, “I’ve never met someone like you,” and I felt like that was a real turning point for us. Maybe she was like, OK, maybe you’re not going to grow out of this thing that I was trying to protect you from, maybe this is something I should be supportive of and let you have. At the same time, there was a part of me that was like, “Maybe you were right about 95 per cent of the things you warned me about.” [Laughs] Now that I’m older, I can see why she was the way she was in a way that I just couldn’t when I was younger.

You’ve also written recently, for Harper’s Bazaar, about your relationship with your father. Your writing about your mother bears a sense of tribute, a spirit of eulogizing. How were the stakes different writing about your dad, who is still living?

There’s less time to understand exactly how I feel. You know, my mom died almost seven years ago, and I’ve had more time away from that experience—and have spent more actual time writing about it. My estranged relationship with my dad is pretty new. It’s harder for me to approach it with the compassion with which I approach writing about my mom.

But I also think it’s less straightforward. [With Crying in H Mart], there’s not much to argue about with actual grief. I don’t fear people misunderstanding the book. Making the decision to be estranged from my father is more up for debate. People have more of an opinion about it, and that makes it scarier. It’s complicated. I’m still very emotional about it, more sensitive about it, weirdly.

Someone wrote a think piece about [my essay in Harper’s Bazaar] that talked about how I wasn’t being fair to my father, and it freaked me out. You know, the New York Times reached out to him [for a piece about the memoir]. He’s supposedly read the book—I don’t think he actually did—but they got a quote from him, and I was really upset. I felt like I had been so generous in what I had been willing to share in both the interview and in the book. I had created a boundary they still felt they needed to cross. So, something I had been really excited about became this shameful, devastating thing. Since that happened, I think I’ve realized I’m not ready, or I need to become a stronger person, or I need some more distance from it. I feel a lot of guilt still, which I was able to let go of with my mother. Over time, maybe I’ll have a better understanding of it.

I recently did another interview with a writer who told me she wrote about things she was scared of, that writing was a way of unscaring herself, facing her fears. Do you find that to be useful?

I do. I think that’s why I wrote that Harper’s Bazaar piece. Knopf and my agent were both like, Are you sure you want to come out with this right before your book comes out? My thought process was that—it really scares me. I was really scared of putting it out in the world. But it was also exciting, because I thought that was why it could be really good. I’d never seen someone talk about this, and I think a lot of people probably go through it. This girl I know wrote to me this really long story about her father, who, after her mother passed away, did a very similar thing, and it really put a strain on their relationship. Even after I had that horrible think piece written about how unfair I was [to my dad], and which I felt so misunderstood and fucked up about, getting that message made it so worth it, knowing that someone else was so fucking lonely and confused about this experience and got some comfort from it.

I think that’s what drew me to writing this book in the first place. I was able to purge a lot of feelings. It was less about fear, maybe, and just that I was fucking confused. It was a whirlwind of stuff that had happened in a six-month period of time and I needed to write it down to make sense of it. There was a real feeling of, like, I need everyone to know what I went through. I felt like no one could see or know what I had went through unless I put it down in this particular way. That, more than fear, was what propelled me—what “propelled” me? [Laughs]—what was the force behind this book.

What are you writing now?

I don’t want to do anything for a while. Between the album and the book and the soundtrack I’m putting out later this year—it’s been such a whirlwind of press. I’m getting ready for tour, and lots of stupid livestream videos, and I’m trying to just not have a project for a while. I’d like to write some shorter, fluffier stuff—something that’s not like, unpacking trauma. My UK press person was like, we’re trying to pitch some stuff, do you have any ideas? I pitched an idea about a short essay about my relationship with chess. Like everyone, during the pandemic I watched The Queen’s Gambit, but when I was younger, from fourth to seventh grade, I was a big chess player. I went to clubs, I like, saw a Russian tutor, I went to tournaments and stuff. I think a lot of people go through this experience of like, they’re naturally gifted at something but they’re not exceptional. Confronting that early on in your life—like, when you get to that ten percent of the top people [in a field], it’s impossible. My father- in-law was almost a professional soccer player and didn’t quite make it. It’s like the gymnast who’s extremely talented but then suffers an injury or something. Those types of first loves, I think of them as little deaths in our lives, and I’m curious how they impact people, where they live inside of us. I’m also interested in having something in my life that is just pure hobby, because everything I’ve done has become, weirdly, my job in some way. So I’ve started playing online chess and really enjoying it.

But they didn’t want it! They were like, Can you write about your estranged father again? [Laughs] I don’t want to! I want to write about my Russian chess tutor. I feel like I’ve unpacked enough trauma for a lifetime. Now I can write something a little gentler and cuter. [Laughs]