It’s odd that going to another country makes people feel obliged to go to museums. I was travelling around Croatia last week with my sister, and it became a running joke that we would visit all the things our Rough Guide described as “boring.” A “dull display of regional crafts,” the guide said about the Rupe Ethnographical Museum in Dubrovnik. A “boring second-rate cemetery,” the guide quoted novelist Miroslav Krleža as saying about Zagreb’s Botanical Gardens.

I love museums, personally, but I often see people gamely trudging through rooms of relics with their fidgety children, glazed eyes, and bulging fannypacks and wonder if they’re enjoying themselves at all. It seems like a quaint hangover from another time, when travel was an extension of one’s formal education; we are supposed to come back having learned something about Roman architecture, medieval ship-building, or Renaissance painting.

At Zagreb’s Museum of Broken Relationships, what we are supposed to learn is not confined to a particular drawer of history, boxed up with identifiable facts and figures. The museum’s mandate outlines a teaching mission that is both simple and wildly ambitious. “Our societies oblige us with our marriages, funerals, and even graduation farewells, but deny us any formal recognition of the demise of a relationship,” the curators write, and the museum is meant to create a public space for mourning the death of a relationship. They hope that the objects on display can “inspire our personal search for deeper insights and strengthen our belief in something more meaningful than random suffering.”

The museum, which is the brainchild of Olinka Vištica and Dražen Grubišić, started as a joke. Vištica, a film producer, and Grubišić, a sculptor, used to date, and when they broke up they talked about how funny it would be to exhibit the detritus of their failed relationship as its own art installation. In 2006, they did, and asked their friends to contribute testaments to their own romantic misery as well. The exhibition has toured the world, acquiring new artifacts everywhere it lands, and found a permanent home in Zagreb in 2010.

I’ve been packing up my house recently for a move, and it feels like everything I pick up is something my ex-boyfriend gave me. Books with sweet inscriptions, a tiny turtle he gave me for my birthday a month after we got together, notes and letters. The break-up is still vivid enough that I burst into tears at Value Village the other day when Gotye’s “Somebody I Used to Know” came on. Break-ups tend to be a bit like that—a lot of crying by yourself into a rack of second-hand dungarees.

So I was a bit worried about visiting this museum, even though the Rough Guide promised it would plumb “the more tumescent recesses of the human psyche.” I’m not sure it’s possible for a few rooms of bedraggled wedding gowns, bottle openers, prosthetic legs, and broken glass to alleviate the sense of random suffering. But there are lessons to be learned at the Museum of Broken Relationships.

First, the visitor discovers what I suspect we all already know: that long distance is the worst. The first room is full of airline tickets, maps, and a touching collection of barf bags—from Croatia Airlines, Hapag Lloyd Express, Lufthansa, and German Wings. The artifacts are all accompanied by written explanations from their donors, and the owner of the barf bags writes: “I think I still have those illustrated safety instructions as well, showing what to do when the airplane begins to fall apart. I have never found any instructions on what to do when a relationship begins to fall apart, but at least I’ve still got these bags.” Nearby, there is a display labelled, “We broke up on Skype,” with a print-out of the break-up Skype chat sewn into a tidy booklet.

Then, that the political is personal. One artifact is a letter in a child’s loopy handwriting, written in May of 1992. “Escaping from Sarajevo under fire in a big convoy, we were held hostage for three days when leaving the city—a few days before, I turned 13.” In the car opposite his, a girl his age with blond hair was also trapped. They talked through their windows; her name was Elma, and he lent her some tapes he had brought. He wrote the letter to tell her that he loved her, but “I didn’t get time to give her the letter because after three days they suddenly freed us. We lost sight of Elma’s car near Travnik.”

It’s possible that three days is the optimal time for some relationships. A silver watch from Bloomington, Indiana, is accompanied by this text: “The first time my ex told me he loved me, he took off my watch and pulled the pin out to mark the time he said it. After that I could never bring myself to push it back in or wear it again.” This sounds like a lovely gesture, the sort you only wish your partner would make. The text goes on, “But if I had known then that he was really only ever going to steal my time, I would have pushed it back in and walked away instead of waiting too many years for my life to start again.”

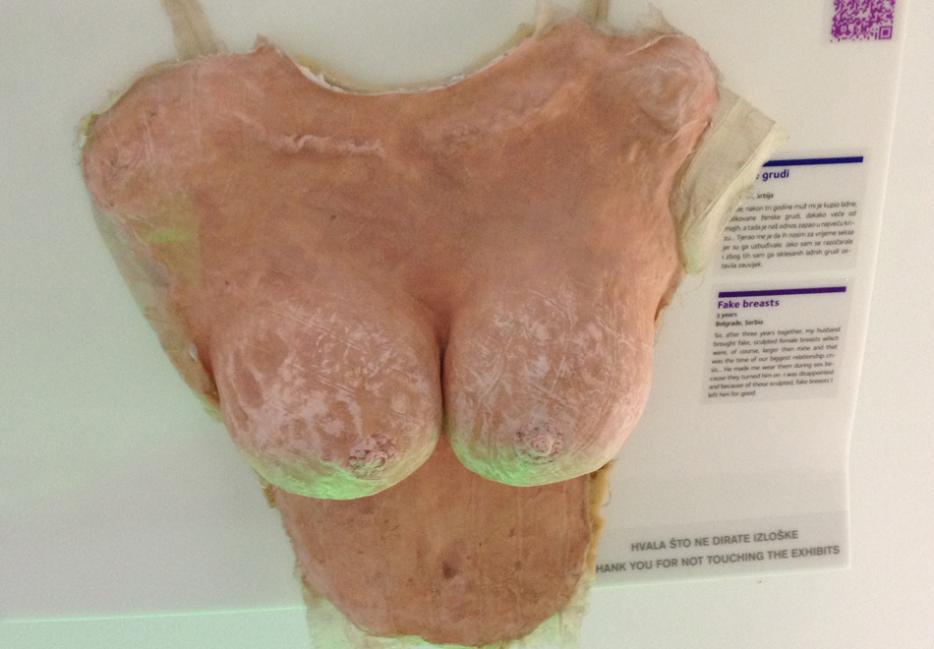

I had expected the museum to be sad; I hadn’t realized how comforting it would be. At least, in the depths of our random suffering, we’re not alone. It’s nice to hear that someone from Belgrade spent six years in a relationship and ended up with nothing but a plastic bag full of olive pits. Or that someone else finally broke up with her husband after he made her wear fake breasts in bed—the breasts are there as proof, accompanied by a card saying “Thank You for Not Touching the Exhibits.”

Vištica and Grubišić are right—society needs to be educated about break-ups. We’re confused about how to manage their dual status as private and public events; while love is between the two of you, a relationship, as a rule, is a social entity that you trot around in public like a dog. People think it’s cute, they ask after it and describe you to other people in terms of it, and when they stop seeing you around that particular park, they’re not sure whether to ask what happened. A museum whose subject is emotion provides a different kind of education from one that lays bare the intricacies of Venetian shipbuilding, but it is nonetheless educational—it helps us learn how to be kind to one another.

Image courtesy of Robert Nyman via Flickr