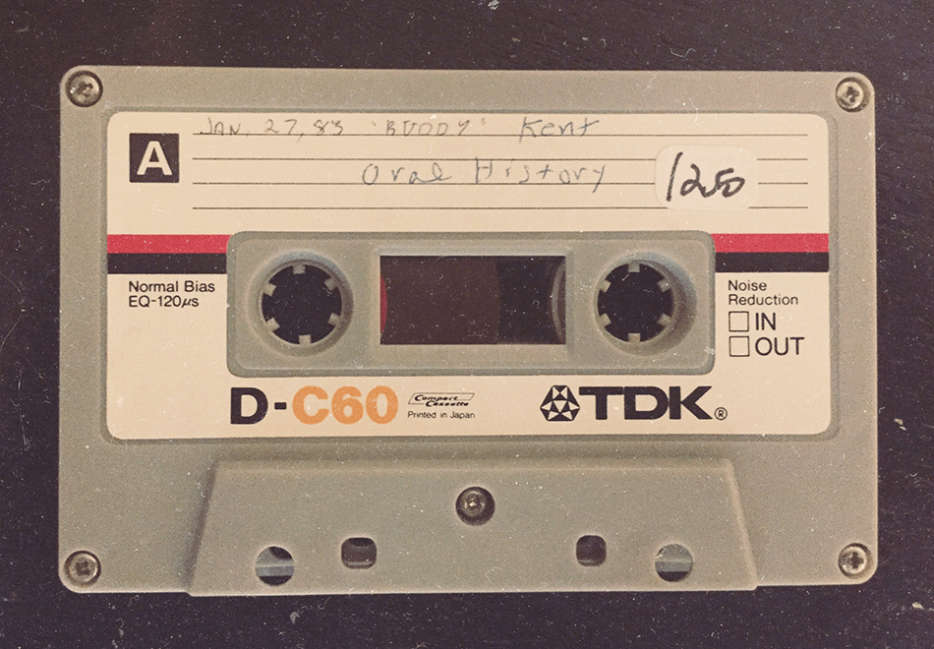

The recording begins with a prickly hiss of static, and a word rendered incomprehensible by the stretching of magnetic tape, before a woman’s voice becomes audible.

“-ZZZSSseries of interviews, 1983.”

“Okay.” Another woman, her voice deeper, raspier, older. A smoker?

“Buddy, talk about your childhood.”

The interviewer is Joan Nestle, perhaps the most famous lesbian historian in America. Aside from her books—A Restricted Country and The Persistent Desire, among others—Nestle is primarily known as the co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA). Inaugurated in 1974, the LHA is “the world's largest collection of materials by and about lesbians,” according to their website. Until 1992, the archives lived in Nestle’s apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Today, they inhabit an entire brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, a neighborhood known in part for its significant lesbian community.

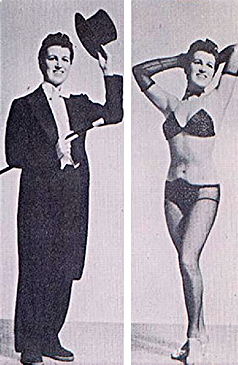

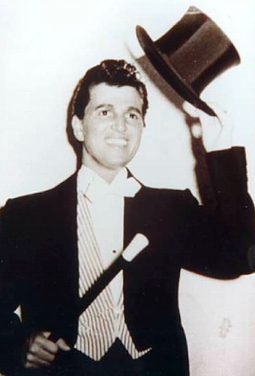

The interviewee is Malvina Schwartz, a.k.a Bubbles Kent, a.k.a Buddy Kent, one of New York City’s reigning drag kings from the Forties through the Sixties. Her publicity photos show a slim woman with a handsome face, dark hair, and a big smile. On the tape, her tone is no-nonsense but relaxed, a slight New York accent peeking through when she drops her R’s—nevah, evah. Near as anyone can figure, she was born in 1921, making her sixty-two at the time the tape was recorded. Or maybe it’s tapes, plural? I don’t have the original, just a CD that skips and jumps, presenting snippets of interview out of order, the story of a police raid on a drag show suddenly giving way to a description of the mobsters who controlled the gay bars like an iron fist latched ‘round a limp wrist.

The interviewee is Malvina Schwartz, a.k.a Bubbles Kent, a.k.a Buddy Kent, one of New York City’s reigning drag kings from the Forties through the Sixties. Her publicity photos show a slim woman with a handsome face, dark hair, and a big smile. On the tape, her tone is no-nonsense but relaxed, a slight New York accent peeking through when she drops her R’s—nevah, evah. Near as anyone can figure, she was born in 1921, making her sixty-two at the time the tape was recorded. Or maybe it’s tapes, plural? I don’t have the original, just a CD that skips and jumps, presenting snippets of interview out of order, the story of a police raid on a drag show suddenly giving way to a description of the mobsters who controlled the gay bars like an iron fist latched ‘round a limp wrist.

The history of that recording is a microcosm for queer history itself: fragmented, discontinuous, and surprising to the modern ear. It came to me sideways, passed from queer hand to queer hand—from Kent to Nestle, from Nestle to the author Lisa Davis (who used it as research for her period lesbian murder mystery, Under the Mink), and finally from Davis to me.

Along the way, the details of its creation have become murky. Nestle only remembers interviewing Kent once, in the small Greenwich Village studio that Kent had inhabited for decades. But in parts of the recording, she occasionally makes reference to earlier conversations, and plans future ones. The Lesbian Herstory Archives have a tape marked “Buddy Kent,” but it has even less material on it than my CD, leaving me to wonder whether I’m holding multiple interviews stitched together by the random forces of glitch, or if there was only one interview, with a second tape that never made it into the Archives.

This is queer history: A game of telephone played down the decades, preserved by passionate individuals and community institutions working on the margins; half-forgotten documents telling of wholly forgotten times, of lust and fear, shame and pride, butches and femmes, lovers and fighters.

This is the story of Malvina, and Bubbles, and Buddy—and Lisa, and Joan, and me, and too many more to be counted, each reverently preserving the pieces we’ve been handed, each looking for a little bit more.

*

Malvina:

I was born in Manhattan. We moved around a lot. I don’t even remember the names of the schools I went to because we moved so often ’cuz my father never worked.

When I was a senior in high school, my mother used to give my sister fifty cents to follow me. She’d say “Follow her, see where she goes. She comes home at midnight!”

Of course I was in the Village, visiting the bars. I didn’t drink; I was a good clean-cut kid. I was into sports and school. I was the star athlete. And very innocent, ’cept I knew I was gay.

Greenwich Village was my territory—like what Israel means to the Jews today! You didn’t have to conform because in the Thirties and Forties, there were so many theatrical and aesthetic people around, and they dressed real weird. Nobody would pay you any mind. The blacks and whites were integrated here, intermarried, so it was like a melting pot. It was really the only place in the city where you were accepted without being looked upon as strange.

I’d go to the bars and listen to music; cruise the glamor girls and lie about my age. Then I’d come home and wash out my one shirt, so I could have it clean for the next day. I always wore a white boy’s shirt, a bow tie, and always a navy blue or black skirt. I’d have my mother slit the side and put a pocket in it, so it would feel like pants. I had curly hair so I’d slick it wet and make it straight. And men’s shoes, because I had big feet. In those days you didn’t wear stockings until you were eighteen or nineteen. First of all they were expensive, and second of all you just didn’t wear them. Your mother didn’t get them for you. So when you came down to the Village you took your socks off, put them in your pocket so you’d look older. Because at sixteen, you wanted to look eighteen. I would order a rum and Coke, take the rum, and throw it on the floor. I’d keep the stirrer in the Coke so it would look like a mixed drink and I wouldn't feel like a kid.

Then I graduated high school, just under seventeen, and I wasn't prepared for anything ’cept college. ’Course, that was out of the question with my family. So the next thing was to get a job.

I went roller-skating for AT&T, the telegram company on Chambers Street. At the time, they didn't hire Jews and they didn't hire lesbians, so I had two strikes against me. I let my hair grow a little bit, wore some lipstick, and bought a cross. And that's when I changed my name.

Then at eighteen I was of age and I walked into Ernie's, got my first job as a bartender, which I had never done. When Ernie interviewed me, he said, "What do you do?" And I said "Everything, everything."

So he put me behind the bar, and I was in full drag at this point: pants, vest, shirt, tie, short hair. I worked like that for a year. Then the liquor board came in and thought I looked too young. One reached across the bar, touched my face and said, “He isn't even a shaver!” But Ernie had all the connections. He took the men in the back, paid them off, and from then on, he said, “I'll have you tend bar from eight to twelve. After midnight a girl cannot be behind the bar.” Because now my cover was blown: I was a girl.

So from twelve to three I mingled with the customers. I danced with the men, the women, whatever. Drank with them, got commissions. And my salary started getting a little better.

Then one night they were short of acts and Ernie came to me and said, "Do you do anything?"

And I said, "Oh, yeah! I dance."

Well, I had [only] done high school tap dancing, but I had a lotta gall!

I got up, I did a number, and they were stuck. They said, “She looks like she’s got some potential.” They helped me whip together a real act.

*

For over thirty years, The Gay Center in Manhattan has been home to a lecture series called Second Tuesdays. It is the longest continually running queer cultural event in the city (and perhaps the world), and it was there that I first encountered Lisa Davis, and through her, Buddy Kent. Davis was giving a reading from Under the Mink, her mystery novel set in Greenwich Village in 1949, which had recently been republished.

In the novel, Blackie Cole is the star attraction at a mob-controlled bar where everyone works in drag, from the wait staff to the performers. In the men’s room one evening, she stumbles across the murdered scion of one of the city’s first families, and soon finds herself caught between the law and her employers.

Fiction it might have been, but fantasy it wasn’t: During her talk, Davis explained that as a young academic working at Stony Brook University on Long Island, she’d befriended a group of older lesbians, women with names like Toni the Stripper, Sully Sullivan, and Augusta “Gus” Cole. Her book was based on their lives. Not the mystery bit, but the really interesting stuff: The world of America’s 1940s drag superstars, the swells who came to see them, and the Mafiosi who kept everyone on the take and made it all possible.

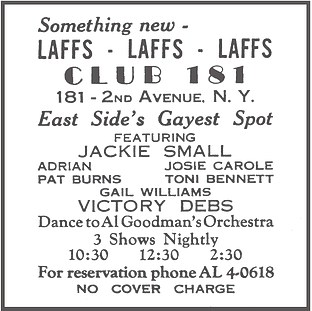

“The clubs run by the Mafia were very elegant,” Davis told the audience. These were places like the Moroccan Village and The 181 Club, where wealth and privilege kissed up against debauchery and vice.

“The clubs run by the Mafia were very elegant,” Davis told the audience. These were places like the Moroccan Village and The 181 Club, where wealth and privilege kissed up against debauchery and vice.

This was in contrast to actual gay bars, which were also run by the mob, but were dank little dives. After all, they catered to gays at a time when homosexuality was widely persecuted. No one was going to protest the shitty conditions or watered-down drinks when just being seen in one of those places could ruin your life. Many of these establishments existed literally in the shadows, beneath New York City’s two former elevated trains.

“Most of the bars in the Village were lesbian,” according to Davis’ research. “The boys were uptown under the 3rd Avenue El. The girls were downtown on 3rd Street, under the 6th Ave El.” Most of the places, such as Benny’s Wonderbar, Tony Pastor’s Downtown, Elle’s Bar, Mona’s, Provincetown Landing, and The Welcome Inn, are only dimly remembered today, if not entirely forgotten.

While the union of dykes, fairies, and goodfellas might seem unlikely, there were a number of reasons for this connection, as C. Alexander Hortis documented in his book The Mob & The City. Prohibition had trampled New York’s nightlife, forcing it all underground; the 21st Amendment made bars legal again in 1933, but by then organized crime had a stranglehold on the business. Add to that the fact that it was illegal to serve drinks to known homosexuals (a law that remained on the books well into the Sixties), and the mob’s knack for finding the silver-lucre lining to every outlawed activity, and gay bars were suddenly an attractive business proposition—a bit of turf they were more than willing to defend. As one bartender told Hortis, “Even if you came in [and] tried to open a gay bar, you would be contacted by the Family, and be informed it was a closed shop.”

Despite our modern association between “the working class” and homophobia, scholars such as George Chauncey have shown that immigrant working-class men (and, in particular, Italian men) in early 20th century New York were actually more likely than other men to engage in same-sex sexual activity, as well as in many other kinds of non-marital sex. Less is known about the sexuality of working class Italian women, but in the Fifties, The 181 Club (where Buddy worked for a time) was run by Anna Genovese, wife of Vito Genovese, one of the heads of the Genovese crime family. According to the women Davis knew, “Anna was definitely into the girls.” This presented quite the issue for them, as they had to navigate her advances without alienating her, or being seen as a threat by her husband.

All of this information, and more, flowed freely from the women Davis knew, many of whom still lived together some thirty years after their time in the bars had ended. In fact, when she died, Buddy still lived in the same building as Kicky Hall and Jackie Howe, two of the nightlife impresarios who helped launch her career. All of them have long since passed away, but I asked Davis out for coffee to learn more about the forgotten world in which they once were stars.

“When they got together, it’s all they talked about!” Davis recalled with a staccato laugh. Short, grey-haired, and wiry, she’s about the same age now that Buddy was when Joan Nestle interviewed her. “You’d think that for gay girls, working for the Mafia would be some kind of scourge—it was the greatest thing that ever happened to them!”

And yet: They didn’t want their stories told. Not by name, not while they were alive. But Davis sat in the background, listened carefully, took notes. When they threw away their photos—the publicity shots for their latest routine, say, or the candids they took with customers for a fiver—Davis rescued them from the trash. Little by little, she assembled an archive of anecdotes and abandoned ephemera. The stories became Under the Mink, and an amalgam of once-famous drag kings, including Buddy Kent, became its protagonist, Blackie Cole.

*

Bubbles:

When I was twenty-one, The 181 Club was hiring attractive lesbians to wait tables. If you had any talent, they put you in the chorus. So I became a chorus boy/waiter. We were all making money and buying cars and really living it up.

I did a strip out of top hat and tails, a Fred Astaire dance and then—with one flip of the hand—my pants flew out from under me. Then I went into a girl strip. When I finished people didn't know if I was a boy or a girl because I was quite slim and very flat.

Next I worked with Kicky Hall and his Review. We went to Atlantic City, the Jockey Club, which was very gay. Did three shows a night, mingled with the customers. The tips and the salary were fabulous. We worked seven day weeks for three months. Then we came back to the city and Kicky booked us into The Moroccan Village. The shows were very professional there. Besides your own act, you did the opening number, a chorus number, and the closing. They had a cover and a minimum, which in those days was a lot. And everybody made money.

When we had money we didn't pocket it or anything, we lived it up! We were all twenty-two, twenty-three, and our life was a bold big bubble. You tipped the waitresses, and you tipped the band to keep playing, and you bought everybody drinks. And some other night maybe you were by yourself without a live wire, and everyone else was buying you drinks.

After the shows, we’d all go to Yank Sing’s Chinese restaurant. Everybody who was anybody in showbiz would appear there. So from four to six am you were either at Yank Sing’s or Reuben’s. On your night off, still in full drag, living as a man, you’d be going to nightclubs like the Copacabana or the Latin Quarter. The girls there all knew who we were because they would come to our club, cruising us. It was quite the thing be seen around town with a lesbian.

Moms Mabley? She was a very good friend of mine. We used to go to the Theresa Hotel, Frank's Restaurant, and Johnny Walker's—that was the one black gay bar, uptown. Billie Holiday used to come there, and Lionel Hampton, Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan. Everything was accepted. You were just another freak, barking along.

Downtown, you saw an occasional black, but it just wasn't done. We had mixed acts even while we had segregation in our club, but we still drew all white people. The only [venues] where the blacks really integrated was Atlantic City after 1960.

When The Moroccan Village had a shooting—nothing to do with the lesbian thing, just a crazy shooting—the club was closed and I moved on again. I wanted to make some big money, so I worked some straight clubs, because I wasn't just a gay act, I was a novelty act. My first straight club was Jimmy Kelly's, on Sullivan Street, the place where The Fantasticks is now. I worked there for a year, which was very unusual because they usually had you work three months. But instead of getting stale, I changed my act, so they kept me on. The Wall Street men liked it. They came to do their little kinky thing with strippers. And I was a stripper, I just was an out of the ordinary one, because I stripped as a man. They enjoyed it. They asked me over to their tables just like the other strippers. So the bosses said, “She might as well stay.”

I was billed as “Bubbles Kent, Exotic Dancer.” I had a lot of gimmicks, but I always came out as a man.

Then Kicky and Jackie decided to get this little place that was doing nothing, The Page Three. We struck a deal with the owners and bought into the place. So finally we were working for ourselves and getting a little bit of the gravy. A lot of very big people used to come down there, like Jimmy Donahue. And the crowd followed us, the hookers and the madams and the kinky guys with money. Our show was a success from the first week.

*

“First of all, I’m a femme from the Fifties,” said Joan Nestle, when I asked her how she came to interview Buddy. Over Skype, her soft grey curls formed a pixelated halo around a smiling face. In a momentary reversal, her voice was now coming to me from the future—these days she lives in Australia, fourteen hours ahead of New York.

But then, Nestle has always been a little dislocated in time—an out dyke before the sexual revolution of the 1960s; a throwback to the bad old bar days during the “new purity movement of the Seventies,” when some lesbian feminists condemned anything that smacked of role-play, S/M, or pornography, including butch/femme bar dykes, such as Nestle and Kent.

But then, Nestle has always been a little dislocated in time—an out dyke before the sexual revolution of the 1960s; a throwback to the bad old bar days during the “new purity movement of the Seventies,” when some lesbian feminists condemned anything that smacked of role-play, S/M, or pornography, including butch/femme bar dykes, such as Nestle and Kent.

“I had been trying to say that these lives were more than roles,” she told me, her voice inflected with passion and, perhaps, a tinge of sadness for having to make that argument. She wanted to prove that the women she remembered from the bars in the Fifties weren’t closet cases pathetically aping heterosexual romance; they were as real and complex and queer as anything that happened after the Stonewall riots. “What that meant is that with my little tape recorder I interviewed every pre-1960s lesbian I could find.”

This was predominantly an organic process, one woman introducing her to the next. And one of the easiest ways to meet these women was through SAGE, Senior Action in a Gay Environment (now Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders). Founded in 1978, SAGE was one of the first social and support groups to provide for elder queer people, who often face the mounting pressures of growing older with a legacy of economic, medical, and emotional baggage from long histories of homo- and transphobia.

“Buddy was very big in SAGE because she’d worked in clubs all her life, so she ran their social,” recalled Lisa Davis. In the pre-Internet world, SAGE was like a freewheeling family reunion, reconnecting queer people whose lives had overlapped at one point and then spun away from each other. A place where exes and rivals and long-lost friends bonded together over the one identity they all shared: survivor. From her decades in the bars, Buddy knew everyone. So after Nestle interviewed Sandy Kern, another SAGE-going working-class butch from the Forties, Kern told her that she had to talk to Buddy.

“Getting into her apartment…” Nestle slipped into a reverie for a moment, clearly re-living the experience. “She just opened the door a little bit and—”

Nestle paused, refocusing.

“I think I must have reassured her off mic that she would have control over these tapes,” she said in a more serious aside.

Buddy was nervous: She had three siblings: two straight brothers, and an older gay sister. Davis and Nestle both recall another generation of relatives—nieces, nephews?—but neither knows anything about them, not even if they also took the last name “Kent.” A link, broken.

It was the history that Nestle and Buddy shared—their time in the bars—that eventually convinced Buddy to open up. “Buddy talked to me because I was a working-class femme who had a crush on her from the minute I saw her,” Nestle recalled with a sly smile.

There is an undeniable undercurrent of the erotic to the tape. Nothing so specific as an outright seduction, but a tension, a backdrop, a potentiality, excitement in a protean form, capable of becoming sexual, but not necessarily so. It is the frisson of recognizing your secret self in another, and it wafts through the entire field of queer history like the smell of poppers at an orgy: omnipresent and un-locatable at the same time. For queer people, community and sexuality are conjoined twins; you can’t reach for one without touching the other.

There is an undeniable undercurrent of the erotic to the tape. Nothing so specific as an outright seduction, but a tension, a backdrop, a potentiality, excitement in a protean form, capable of becoming sexual, but not necessarily so. It is the frisson of recognizing your secret self in another, and it wafts through the entire field of queer history like the smell of poppers at an orgy: omnipresent and un-locatable at the same time. For queer people, community and sexuality are conjoined twins; you can’t reach for one without touching the other.

But as desire motivates, so can it distort, and the excitement of discovery can obscure the reality of what has been found. Because queer history is so rare, and there is such a palpable thirst on the part of queer historians like myself to connect with these ancestors, it can be easy to focus on the exciting parts of their stories, to turn them from real people into clickbait headlines: You Won’t Believe These 14 Photos of Historic Drag Kings! Buddy’s life as a performer was only one small part of who she was, but it’s the best-documented part because that’s where her life intersected with the lives of straight people, who had money.

Halfway through a question, Nestle stopped our interview, agitated.

“I hear the wonder in your voice and…” she trailed off, picked at some invisible thing on the arm of her chair. “How can I put this? Buddy's life wasn't exotic. It was real. She was a working woman. She had talents and she wanted to use them to pay her rent, help her girlfriends. The real importance [of that tape] was how it showed the every day nature of making a life as a different kind of woman.”

*

Buddy:

The butch always protected the femme and carried the suitcase. If you happened to be a butch with a heart condition you were really in trouble because you couldn't carry the suitcase and you were ridiculed. The girl never drove the car, even if she owned it. If the butch didn't drive, they parked somewhere on the side streets so nobody saw. If the girl was a better dancer, you still had your hand in the leader’s position even though she was pushing you into the steps. You paid the check; she handed you the money for her share.

At home, the butch never did the cooking, unless she was from a big old Italian family and she was really a terrific cook. But then if they had a party it would all be pre-prepared, so the girl could be in the kitchen and heat it up. The butch greeted you at the door, took your coats. The femme sat you down and offered you food, while the butch got your drink. It was a very heavy role play time.

There was love, yes, but I think the dykes many times weren’t sexually fulfilled. The butch played the role of satisfying the female, and that was it. There were some dykes in the Thirties who were using dildos, but that was very rare. But the ones who were had those two-sided ones, so evidently they were getting their satisfaction! The relationships that lasted longer, I think, were the ones that were sharing sexually.

But there were very intense loves and then there were casual loves, just like in a heterosexual relationship. There were couples that stayed in love and romance for years and years, and then there were some that fell into a pattern of married life and it was just a matter of not being alone.

The women were strong in those days. First of all they had better jobs than the dykes, who were limited to factory work, because that's where they were accepted. They were like the token freak of the company. The femmes who couldn't be identified because of their appearance could have good jobs.

Also, if you went out on the weekends, there’d be catcalls, and the butches wanted to be protective. It was the femme’s point to come between them and say, “Just don't bother, we're not going to win.” They really had to be the stronger one because they knew it would be a losing battle. The girls used more sense. And actually the dyke at that point wanted to be stopped, but felt they had to come through for their image. When I stop to think of it, the butches were the biggest crybabies. Try to get them to a dentist or a doctor, they fell apart.

We didn't have what you have, consciousness raising groups. You had to work out your own problems or you became a neurotic who fell by the way side. A lot of gays wound up psychotics, alcoholics, or junkies, because they couldn't cope.

*

Try as I might, I can’t establish a date of death for Buddy. Not even the year, or the place she was buried. I’ve searched every permutation of every name she ever used—Bubbles Schwartz; Malvina Kent; Buddy Schwartz-Kent—but no obituary ever comes up. Even in death, however, she stuck with her friends from the bars.

“Jackie Howe got sick,” Lisa Davis responded, when I asked what happened to Buddy in the end. “She went to stay with some of her family, who of course threw her out soon after. And she died. Then Buddy's sister died, and Buddy just didn't care much anymore, so she died, too.”

There’s a whole section of the tape that sounds just like that, Tito Puente playing in the background, Buddy flipping through a photo album, pointing out the women she knew and what had become of them:

Let's see. That's Dean, she's dead. Very, very attractive. She OD’d. This was Jackie Howe, she's downstairs. That's Rosita, she was a hooker. She’s dead. This was a pimp; that was one of his whores. This was the millionaire who used to come around the clubs buying everybody drinks. That’s a girl I went to high school with—not a success story. Dead.

On the tape, Buddy said she stopped working in the bars some time in the Sixties, as first television, and then disco, stole the crowds away. The dawning world of lesbian feminism, with its focus on radical politics, left many bar dykes behind. So when they closed The Page Three, Buddy traded in her dancing shoes for an X-ray machine, and became a technician at St. Vincent’s hospital, a job she loved. New bright young queer things appeared, at Studio 54 and The Wow Café, and the fog of time swallowed the 181 and the women who were its kings.

On the tape, Buddy said she stopped working in the bars some time in the Sixties, as first television, and then disco, stole the crowds away. The dawning world of lesbian feminism, with its focus on radical politics, left many bar dykes behind. So when they closed The Page Three, Buddy traded in her dancing shoes for an X-ray machine, and became a technician at St. Vincent’s hospital, a job she loved. New bright young queer things appeared, at Studio 54 and The Wow Café, and the fog of time swallowed the 181 and the women who were its kings.

The old bars closed; the old dykes died; the new world moved on. We forgot, and then we forgot the very act of forgetting, and like that, Buddy’s world disappeared from our popular consciousness. Queer history, like all marginalized histories, is a fragile thing with limited infrastructure to preserve it and pass it on. Like a big bold bubble, it shimmers in the sun, but leaves only a tiny, shiny residue when it pops: A tape. Some photos. A dwindling collection of memories. Pieces that will never make a whole. Were it not for the crucial work of Joan Nestle, Lisa Davis, and the Lesbian Herstory Archives, we would have even less.

But then, nothing is ever perfectly preserved. All history is partial, kept only by happenstance, or because it meant something to someone at the time. The best it can do is demarcate the edges of what was once there, sketch out a coastline and write here be lesbians on its uncharted heart, that space where history meets mystery and becomes myth. The power of Buddy’s tape is not just what it tells us about her life, but what it suggests about the lives of hundreds of others. What we know always asks the question, “What don’t we know?” And perhaps the most important part of every interview is the moment the tape clicks off, reminding us of all the life lived outside the range of our recording.

*

Buddy:

There’s only one regret I ever had: that I never finished college. Which I probably didn't want too bad or I could have done it. It's just that I was more interested in money at the time, and cars, and running around. Eventually I probably will. I'm very close to an AA [Associate of Arts degree] now.

But I never—

[end tape]

Recorded interviews have been edited for length and clarity. The taped interviews with Buddy were conducted by Joan Nestle for the Lesbian Herstory Archives and provided courtesy of Lisa Davis.