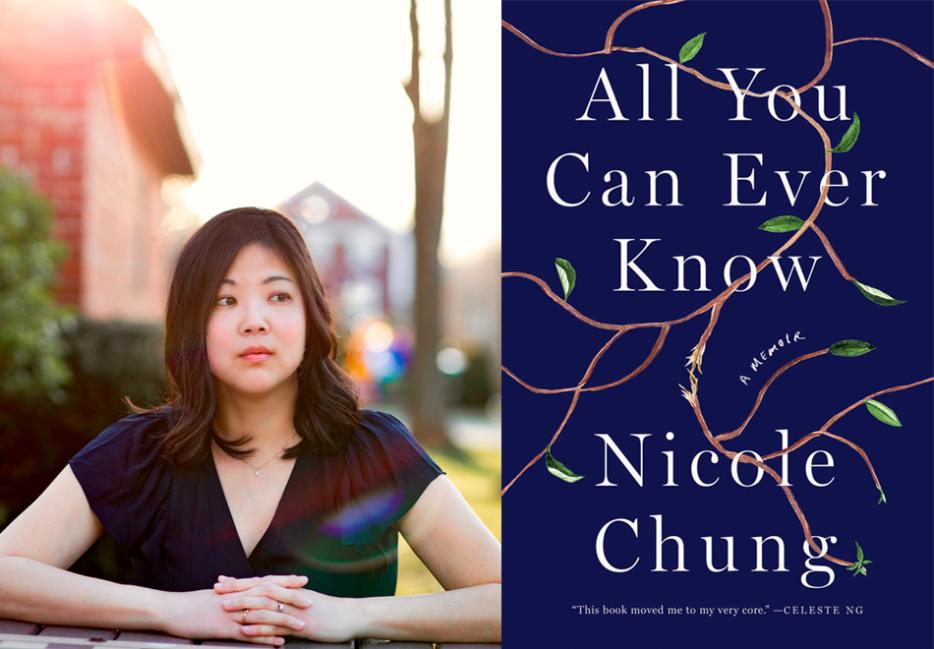

Early into her memoir, All You Can Ever Know (Catapult), Nicole Chung writes about the little ritual she has when she visits her hometown, a small city about five hours from Portland. The moment she gets off the plane and steps into the one-room airport, she begins counting the number of people of colour she sees. She’s usually the only one.

I do this too. When I go back to my hometown, about an hour and a half north of Toronto, I have the same habit. It’s not uncommon for me to be one of the few non-white people in a restaurant, clothing store or bar. (Unless I’m with my mom and brother, who are also Japanese, in which case the number of Asian people suddenly triples.)

Throughout Chung’s beautifully written memoir, I found myself nodding along as I recognized parts of myself in her story. Not that my life story is very similar to Chung’s. Adopted when she was a baby by a white family in Oregon, Chung didn’t know any other Korean-Americans or adoptees growing up. All You Can Ever Know begins in Chung’s childhood, where she endured racist bullying and cruel and tactless questioning by classmates (“Where did they get you?” and “How much did you cost?”) and continues to her eventual search for her birth family and the aftermath of unearthing a family secret.

Although Chung is quick to point out she wrote the book with the intention of telling just her own adoption story—it by no means represents all adoption stories—she also understands why all types of readers are finding it so relatable. She notes how multiracial readers, like myself, have told her they’ve identified with the idea of existing between two different cultures, and how nearly every family has secrets or unspoken truths that are never discussed. It’s these universal themes of family, belonging and identity that make All You Can Ever Know such a compelling read.

All You Can Ever Know is Chung’s first book-length project, but she’s been writing and editing other adoption stories at The Toast, where she was the managing editor, as well as at Catapult magazine, where she’s currently the editor in chief. She’s also written for The New York Times, GQ, BuzzFeed and here at Hazlitt.

I spoke with Chung about when she realized she wanted to turn her search for her birth family into a memoir, having an honest relationship with her own children, the nature vs. nurture debate, and our shared love for figure skater and Asian-American icon Kristi Yamaguchi.

Samantha Edwards: When did you start thinking about turning your story about searching for your birth family into a memoir?

Nicole Chung: I’ve always written about my life, in the sense that I’ve kept a journal since the age of five. I was writing pretty much daily journal entries when I was pregnant and searching for my birth family. I knew I wanted to have a record to refer back to. I pictured just pulling it out and talking to my kids about it, saying, “This is what was happening while I was pregnant with you.” I was thinking of it as a personal origin story that I’d share with just family. I certainly wasn’t thinking, “I’m going to turn this into a book one day.” I didn’t really start writing about it publically until five or six years after I searched for my birth family, after I had my first child. At a certain point, it just felt like there was much more to the story that wasn’t coming across in a piece here and a piece there. I realized a book-length project would allow me to tell the whole story with all of the detail and nuance.

What kind of reactions did you get from readers when you first started writing about your adoption?

It was a range. I heard from a lot of people who were interested in adoption whether it’s because they were adopted, they knew someone who was or they were thinking about adopting a child. Many people had a lot of positive and encouraging things to say and were thanking me for sharing my perspective because the adoptee perspective is historically underrepresented. Most adoption narratives tend to focus on adoptive parents, adoption professionals or people in the industry. There are a lot of conversations about this happening among people who are adopted or people who have adopted, but I don’t think the adoptive perspective has really entered the mainstream. That’s when I realized there’s more here, maybe I have more to say, maybe I can contribute more to the conversation than I thought.

It was really enlightening to learn about the adoption process, especially about the concept of “search angels,” the intermediaries that reach out to birth families on behalf of adoptees. I liked how you said the term “search angel” called to mind “search-and-rescue volunteers” or “the patron saint of lost items,” when really, they’re a business or a service like anything else.

It was challenging finding someone and trusting them with this very intimate business that was so important to me. I remember feeling kind of glad there was this extra layer, like a buffer, between me and my birth family and if they wanted to, they could tell the intermediary no and they wouldn’t have to say it directly to me.

And then when you did meet your father and sister, Cindy, you had a lot of anxieties.

Growing up, I remember thinking, maybe it was something about me that lead to my adoption. This fear I had of being unlovable, or not important enough for people to really want. I think to some degree, that feeling and insecurity has never fully gone away, enough though many people in my life have given me daily proof that they do love and value me.

Even for my birth family, it was much more complicated. It wasn’t like they looked at me and decided, we don’t want you. It was a very complicated decision. I think that fear of abandonment carried over when I re-connected with my family again as an adult. I thought,

“Well, obviously I’ll be more interested in them than they will be in me.” I think that’s where some of that anxiety came from and it wasn’t unfounded. It was based on my history.

How do you cope with those feelings now?

I don’t necessarily think about it as much now. I’ve been married for fifteen years and I have two wonderful kids. In a lot of ways, having a family of my own has been very healing. That’s not why I got married and not why we had children, but I think in a lot of ways, having a family of my own has been huge in terms of me feeling secure.

There were so many coincidental happenings during your life at that time. Like the timing of different things—receiving an email from your birth father when you were in labour, and then getting a phone call from your birth mother when you were with your newborn daughter.

I always found it fascinating how my family expanded overnight. It’s like the search and the pregnancy were on these parallel tracks at the same time. I got the first letter from my birth father when I was in labour. It is really strange and kind of poetic. If it was fiction, people would probably say, that’s a little on the nose. But of course this is how it happened. And when my mother called for the first time, my daughter had just spit up, as babies do, all over me and all over the bed. And in middle of this, that’s when the phone rings. I remember when I answered it, my husband was like, really? Why are you answering the phone now? I still can’t believe the timing of it all.

While I was reading, I was thinking a lot about nature vs. nurture. Is that something you thought about when you were meeting your birth family? I was thinking about how your birth father, Cindy and you all have the same habit of drawing out letters with your fingers subconsciously. It’s so eerily specific it feels like you must’ve been born with that habit ingrained in you.

Sometimes I ask myself, what’s more important, nature or nurture? I’m more like my birth family members than I am my adopted family, but it’s just the way it worked out. I could have been adopted by people who are much more like me, and even if they were white, we could have had much more in common. I’m not sure how much of it is because of adoption or just the particular family that adopted me. As a kid, I felt like there were things my parents didn’t get about me, and things my wider adoptive family didn’t get about me or didn’t value. That said, when I met my birth family, It’s not like I was like, ‘You’re just like me!’, because they’re not. We’re also very different people. Meeting them has given me a little more perspective on who I am and the things that I care about, but it definitely didn’t answer every question I have about myself or the nature of belonging.

Do you identify more with other adoptees or Korean-Americans?

Growing up, I didn’t identify with anyone. I didn’t know anybody like me. I wasn’t close to any other Korean-Americans and I didn’t really know many other adoptees. I do really identify strongly with other adoptees, which is not to say our experiences are the same, every adoptee has their own story, but I do feel like there is a certain guard I let down, a deeper honesty I get to when I’m talking with people who share aspects of this experience. I felt like adoption isolated me, even more than race in certain respects, because no one else really understood the feelings I had about it, and nobody else really understood the question that haunted me. When I meet other adoptees, there’s a level of comfort knowing they fundamentally understand this thing about my life. I do really identify with other Asian-Americans and more broadly, I feel a certain comfort speaking with people of colour. I think there are things in the story that a lot people identify with, even if they’re not adopted or aren’t Asian-American, because of the bigger questions about family and belonging and lies. Everyone has had those questions they’ve asked and their parents don’t answer. Or everyone knows there are family members that you don’t talk about and you don’t know why.

Do you feel like you have a greater desire to be more open with your kids because there were so many secrets and unknowns growing up?

I think so. Within my adoptive family, there was so much love and compassion, but there were things we didn’t talk about. Some of the hardest things I went through as a kid, we didn’t discuss it at all. I think about some of the racist bullying that happened to me at school and how I didn’t feel like I could tell my parents, partly because they’re white, partly because I felt like I had to protect them, and partly because we just never talked about race or racism. It breaks my heart thinking about my kids going through something similar and me not knowing, so I have tried in a lot of ways to have this culture of openness. We just don’t wait for them to bring topics up, we’ll bring it up too so they know the burden is not just on them to break the silence. I do think that’s really important and there is no part of my story that I intend to hide from my kids.

OK, this question is a bit off topic, but we need to talk about our shared love for [American figure skater] Kristi Yamaguchi. I loved her so much growing up. I was actually a competitive figure skater and I had a Kristi Yamaguchi PC game.

Oh my god, Sam! I need that game!

It was amazing! You could make routines for her and design her costumes. A couple years ago you wrote this beautiful essay about Kristi Yamaguchi in The New York Times and how powerful it was to see an Asian-American woman in the limelight. When you saw her on the cover of Newsweek, you wrote, “it was the first time you had been encouraged to think of as an Asian-American woman as beautiful.”

I wrote that essay because I was talking with a friend of mine and we were reminiscing about early '90s figure skating and how Kristi Yamaguchi was a touchstone for Asian-American women of our generation. It was the first time many of us saw an Asian American woman being glorified on the international stage. It was huge for me. I’m still shocked and pleased to see Asian women on the cover of magazines or getting attention for things that they’ve done. But at the time, I can’t even overstate how revolutionary it felt in my life growing up in this place where I didn’t know other Asian people and I was getting pretty serious racist bullying at school for being Asian. It really felt like a lifeline. That was one of those pivotal moments when my perception of who I was and what was possible started to shift, not because I thought I’d be an Olympian. But I had dreams too and they seemed a little more possible, which sounds incredibly cheesy and earnest.

I imagine some people got that same feeling seeing Constance Wu on the cover of so many magazines this summer. I know that sometimes people get tired of talking about representation, but it really does feel amazing seeing people who even kind of look like you on covers.

I also understand the fatigue because it puts a lot of pressure on artists when they’re one of the few that people are looking at. I imagine it’s a great deal of pressure for them to be asked about it over and over again, because they’re just trying to make art or do what they love. But I’ve found it incredibly encouraging and powerful to see. I remember interviewing Constance Wu for The New York Times when she was the breakout star from Fresh Off the Boat. It’s been so amazing to see her star rise and be inspired by how she’s become such a strong advocate for Asian American stories and our artists. It’s been wonderful seeing the attention she’s continued to get. I think it’ll be powerful as long as it’s a little bit rare. Hopefully one day we won’t notice or talk about it quite so much because it’ll be commonplace. For right now though, it’s still very exciting.