High on a parapet, a Babylonian official stalks back and forth. He’s just heard the first thunder of spring. Inside, the official’s colleagues rush to carve the event into clay tablets, which they’ll file deep into their archives. They’ll compare this thunder with that of past seasons and their accompanying harvests, prognosticating the year to come.

No linear time exists without the furious work of these individuals, at once analysts, civil servants, and prophets. With no iPhone or universal clock, there’s no room for mistakes. Tasked with creating and maintaining a calendar, the regularity of commerce, state affairs, and religious holidays depend on their correct calculations. After all, without a set timetable, rent goes unpaid and holy days, ignored. Their accuracy ensures that all societal obligations, both practical and spiritual, are met.

What do we, in the modern age, name these ancient calendar makers? Some might call them astronomers. Indeed, the majority of their work was centered on measurable, predictable astronomical events. Others, still, might call them astrologers.

“Astrologer” is a loaded term in the twenty-first century. It conjures up images of television psychics, with crystal balls and toll-free lines, or your favorite hippie friend who won’t stop reading their horoscope. The gravity of the Babylonian calendar maker’s work is notably absent.

To scientists, the stubborn fixation on a practice that can’t be empirically proven defies reason. To astrologers, science without a spiritual philosophy on which to hang it is empty. The collective ignorance of the common thread between astronomy and astrology has, at times, threatened to unravel the entire tapestry. Neither wishes to be associated with the other, and as such, the work of the Babylonian timekeeper is obscured by their feud.

What the ancient timekeepers and today’s scientists share is that both forms of practice center on the study of what can be seen with the naked eye. Of course, what we can see now with the assistance of ever more complex technology is a far cry from what the Babylonian timekeepers were viewing. It’s natural, then, that as we’ve probed farther and farther into the vast reaches of our unknowable universe, our understanding of the stars would change.

*

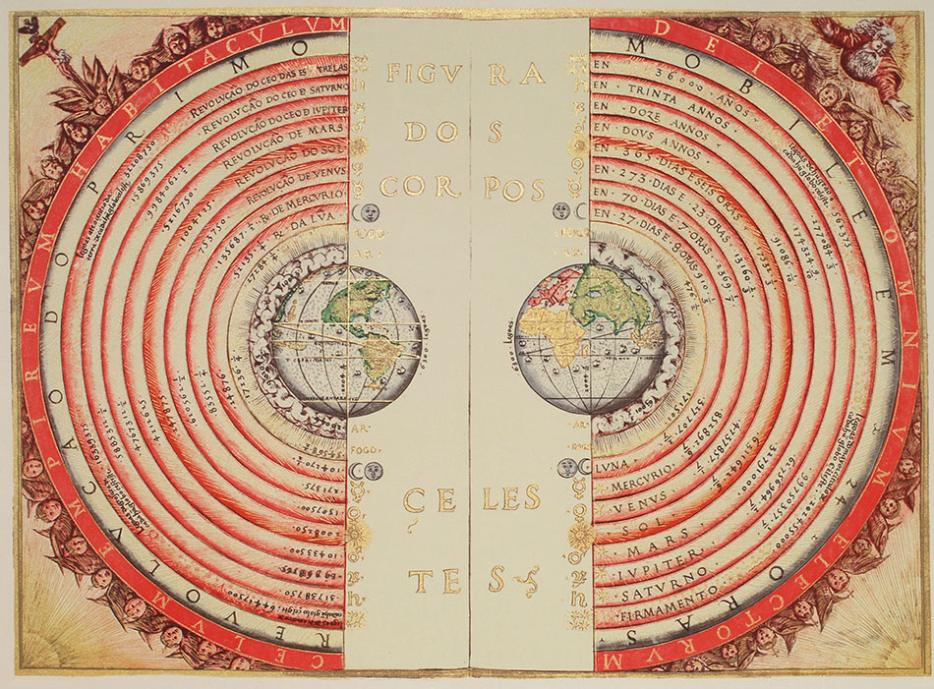

The slow drift away from the philosophical side of astronomical study isn’t new. By the Hellenistic Roman era, people had expanded their worldview to include the advancement of astronomy. By the fourth century, Hellenistic cosmology had shifted from a three-tier hierarchy of the heavens, the earth, and the underworld, to Earth as a sphere suspended in space alongside the other seven visible planets. Traditional local deities shrank in comparison to the empire’s growing understanding of heavenly mechanics. So, people sought a more cosmopolitan explanation—or cure-all—for their problems.

Perhaps that’s where the debate really began. Some insisted on upholding the old way of stargazing—which included the interpretation of both stellar events, like eclipses, and meteorological phenomena, like storms, as omens—while others found it difficult to reconcile new scientific discoveries with their religious practices. Others still found a sense of comfort in using cosmic information to explain the banalities of day-to-day life. Someone’s looks, personality, marriage prospects, future wealth, and more could be explained by creating a horoskopos, or star chart, tailored to a specific individual’s needs.

The blending of astrology, science, and religion produced a sort of science fiction that was practiced by nearly everyone for centuries to follow, from the lowliest farmers to the highest-ranking officials. In particular, governments looked to astrologers to provide auspicious dates for important battles and inaugurations (hence “augur” in the spelling). Because astrology was believed to be such a prized weapon among society’s elites, over time common people were banned from its practice.

The most obvious example of this trend is in the Catholic Church, where astrology was publicly condemned, but top clergy continued its practice. While a few outliers, such as Thomas Aquinas, permitted the observation of the stars in relation to harvests, rains, and “other things coming forth from the heavens,” a host of other saints decried its popular use as a divinatory tool as evil. Saint Augustine famously said that astrology “should be expelled from all Christian nations,” but popes still employed it behind sanctuary doors. Pope Julian used it to choose his coronation day, Pope John Paul II used it to form a council that would be favorable to his wishes, and Pope Leo founded a “chair of astrology” within the University of Rome.

There seems to be no clear line of demarcation between when astrology was accepted and when it fell out of favor. What we know is that astrology was part of the academic canon in the early Renaissance, and by the end, it had been quietly banished to the realm of spiritual study. This could have happened for a multitude of reasons, but two are most likely: the advent of Protestant Christianity and the rapid advancement of scientific discovery. With the entry of these challengers onto the cosmic stage, astrology as harbinger of fate was pushed aside and, eventually, faded into an incense-heavy cloud of obscurity.

Views on star study changed rapidly during the Protestant Reformation, since astrology was seen as a largely Catholic pursuit. Popes were known to be well versed in astrology and supposedly used it to influence international affairs, a practice viewed as deeply corrupt by the nascent movement—though Catholics in power at the time were also suspicious of astrology’s use in foreign affairs, and generally condemned the practice.

In particular, Mary Queen of Scots was conveniently selective in her views on astrology. As a Catholic, her position would have been more lenient than those of the Protestants she opposed, but that didn’t stop her from imprisoning the famous statesman and navigator John Dee for casting a horoscope to discern the length her reign—one that would ultimately assist her sister Elizabeth I in ascending the English throne. The conflation of astrology with this kind of political double-dealing would eventually spell its demise as a publicly accepted practice.

On the scientific front, Copernicus’s revelation that the sun, and not the Earth, was at the center of the known universe threw the existing view of the stars—and astrology—into sharp contrast. As telescopes and, later, satellites began to probe the infinite cosmos, the limits of prediction based only on our solar system cast doubt on belief in its metaphysical influence. If there are millions beyond millions of stars in the sky, why do we ascribe so much power to an arbitrary few?

More recently, some proponents of astrology have tried to use Einstein’s general theory of relativity or the idea of quantum entanglement to grasp at a scientific explanation of its inner workings, but by empirical standards, they still come up short. Yet astrologers continue to innovate in their craft, developing new meanings for the latest discoveries and incorporating them into their work, crafting detailed interpretations for planets far beyond what early astrologers would have seen with the naked eye.

Despite conflicts, what has persisted in both disciplines is a desire to distinguish between charlatans and those with a legitimate claim to practice. Even into the present day, there’s a sense that some astrologers engender more trust than others, though it’s difficult to place exactly why. The reason lies buried in ancient Greek mystery traditions, which required initiates to undergo various dramatic rituals before the secrets of the cult were fully revealed to them. The Greeks took these teachings seriously—so seriously, in fact, that the punishment for defecting could be death.

The most well-known (and closely guarded) of the Greek mystery religions was that of Eleusis. While the teachings didn’t involve astrology per se, its central myth revolved around the harvest goddess, Demeter, and the passing of the seasons. Acceptance into the Eleusinian mysteries was desirable and respected, so much so that itinerant diviners who claimed to offer private initiation at a high price popped up throughout the Greek world. They were such a widespread nuisance that Plato (himself an initiate) addressed them in his Republic, complaining of their fraudulent tactics and “babble of books” in great detail.

Of course, the answer to this problem—like most things relating to star study—is a complicated one. In his book Mystery Cults of the Ancient World, Hugh Bowden explains that the more-than-occasionally unscrupulous private initiators “were at least as often serious thinkers who saw no difference combining an interest in religion with science.” It’s not too far off from modern astrologers, who find ways to reconcile scientific advancement with ancient belief systems.

*

At times, it seems illogical that astrology has continued to exist alongside centuries of scientific development. However, Roger Beck, author of A Brief History of Ancient Astrology and an Emeritus Professor of Classics at the University of Toronto, posits that astrology’s greatest strength exists in it being a common language between cultures and throughout centuries. He calls the complex jargon of horoscopes “star-talk.” Hop into a Twitter conversation with twenty-first century witches and you’ll see it’s alive and well.

“A natural language is a code," Beck explains, "but a public one, with rules and conventions familiar to all its users, in which meaning is expressed and communicated by signs which themselves have agreed and stable meanings.” This is the way astrology really works: as a coded language in which people who seek a higher purpose can communicate. If someone says, “My sun is in Scorpio,” some of us know, culturally, what that means. A single word evokes a laundry list of possible descriptors.

The ancients understood astrology’s symbolic potential too. Consider the Mithraeum, the sanctuary of the cult of Mithras, another of the mystery traditions. It’s decorated from floor to ceiling in depictions of the zodiac signs. Historians believe this was to aid initiates’ understanding of the esoteric ritual in which they participated. Not all initiates would have understood the arcane elements of the ceremony, but the meaning of the decorations would have been evident to anyone who knew about astrology. Even into the Middle Ages and Renaissance, alchemists used astrological symbols to code the privileged and potentially dangerous information contained in their grimoires.

Approaching astrology as a language may be an easy to digest explanation for its persistence, but what of its continued use as a predictor of future events? With horoscopes so readily available, it’s hard to deny astrology’s tenacity. Still, the two threads of star study are more frayed than ever, as astronomy and astrology clash again over reports of a “new zodiac sign” from NASA.

The explanation for the new zodiac sign is relatively simple, though hard to come by. NASA uses what’s called the “sidereal zodiac,” based on the exact position of the stars in the sky, while Western astrologers use the “tropical zodiac,” based on the Earth’s location in relation to those stars. The sidereal zodiac contains a host of different constellations, but because the tropical zodiac is based on Earth, we’ll always have the same twelve signs.

While it’s desirable to think our horoscopes descend from an enlightened time when people were more in touch with their spirituality, it’s not so. In reality, the mystical work of the astrologer was at times mind-numbing, and the mundane work of the astronomer has led to mind-altering discoveries. There was no golden age during which astrology was deeply held and accepted as truth. There have always been skeptics and believers. But despite our differences, we gaze at the same stars.