I have to admit, I wasn’t sure we needed a new book called Modern Whore (IMPULSE[b:]). One of the most pernicious tropes of literary sex work representation is the tendency to make one person’s experience the stand-in for an entire misunderstood enterprise (I Was A Teenage Dominatrix, The Happy Hooker, Ordeal). At first glance, it appears that author Andrea Werhun is the type of sex work memoirist we’ve heard from before: a white middle class humanities student still in her twenties who dabbled in escorting for a few years.

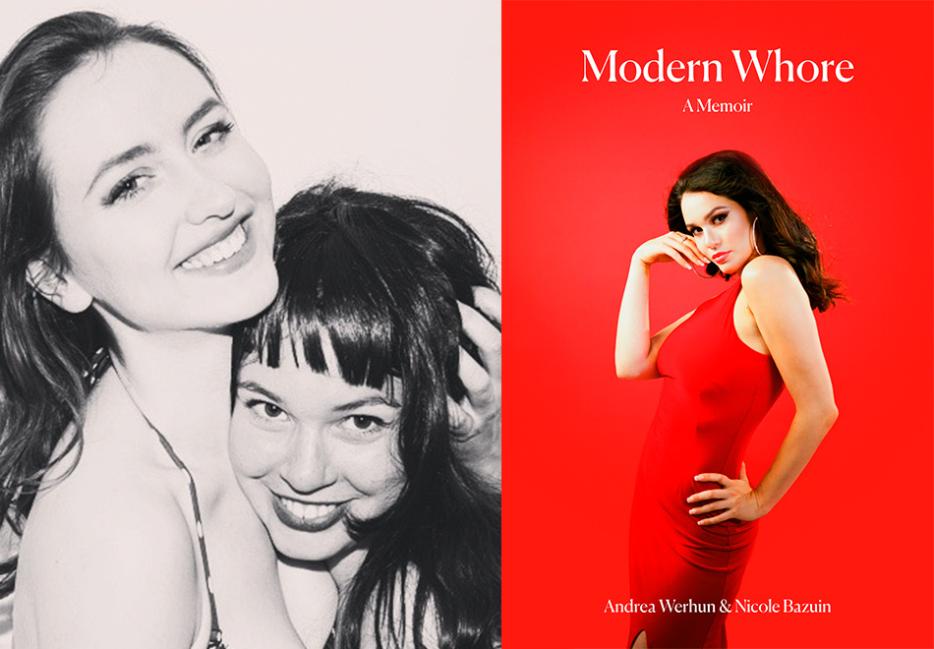

But as Bo Diddley once sang, “You can't judge a daughter by looking at the mother, and you can't judge a book by looking at the cover!” The Modern Whore collaborators—Werhun and her good friend, photographer Nicole Bazuin—have created a self-aware package, starting with the cover image of Werhun in a scarlet cocktail dress and soapy pose. It’s a look that promises both sin and classiness.

The book is a primary colored matte-lover’s dream, an objet d’art that wouldn’t look out of place in the gift shop of a contemporary museum. The photographs that appear throughout the book demonstrate Werhun’s confidence in what her own body can be made to mean, a skill she honed on the clients who paid her for her time, her conversation, and her sexual attentions. Some of the costumed, stylized images have the high contrast irony of a David LaChapelle magazine spread, while others accentuate the drama of the stories.

The modernity of the book comes less from the circumstances of Werhun’s short career as a Toronto-based escort in the mid-2010s than in its variation of form; it’s a one-woman variety show. There’s bald comedy, deliberate vulgarity, classical myth-making, bleak memoir tailor-made for the first-person industrial complex, political manifestas, and zine-like advice for the next generation of sex workers.

I spoke with Werhun and Bazuin about crowdfunding, myth-making, and role-playing.

Tina Horn: What would you say is the most modern thing about the way you designed this book? About the Mary Ann/Andrea character at its center?

Andrea Werhun: We designed the book to reflect the multidimensional quality of the sex worker as a fully fleshed out human being who, like everyone else, must simply carry out a job in order to survive. That’s why, in addition to stories about the work itself, there are tales from my childhood, as well as fiction and fairy-tale. When people stop seeing sex work as a character flaw but as a job, the banal truth of our lives off the clock becomes shocking. I also think the way sex workers compartmentalize their work selves with their civilian selves is a modern concept mirrored in the book as the central character, Mary Ann the escort, is conveyed by Andrea the author. I specifically include the childhood stories to serve as a hypothetical “precedent” for my choice to enter sex work. I play with that idea because so often there is an assumption that all sex workers are victims of childhood abuse because only “damaged” people would pursue such risky, socially-frowned upon labour. Now is a great time to challenge that assumption in light of the #MeToo movement, as we discover almost every single one of us—men and women alike—has experienced some form of sexual abuse throughout our lives, and not every single one of us is a sex worker.

But perhaps most importantly, if modernity is marked by a challenging of tradition, sex workers, who have always been pressured to keep their mouths shut, are now speaking up. I reject the idea that whoredom is universally victimizing, when for many of us, sex work has given us the opportunity to be more fully ourselves. We have more time, more money, more freedom to do the things we want to do, and we are not going to silenced anymore.

Nicole Bazuin: On a practical level as well, the design of our book felt modern because we used the contemporary tools available to us to help bring our vision to life. From its early days, we utilized social media platforms to build an audience for the project and it became a testing ground for the content of the book long before its existence as a printed object. Andrea wasn’t public with her past at the time, and so the “Mary Ann” character, Andrea’s escort pseudonym, became our avatar through which to play. We began to explore the words and images that related to the concept of being a “modern whore,” a woman making money from her sexuality in today’s society and all of the theoretical and visual associations that go along with that, but we didn’t yet know what form the project would take.

When Andrea ultimately made the decision to come out publicly as a former call girl in the CBC documentary Sugar Sisters, the vision for the book as a memoir sharpened, and production on the book accelerated with our growing audience following along. As opposed to creating in a bubble, we were able to share the aesthetic and the vernacular we’d begun to develop, and to trigger discussions surrounding the subject matter. The episodic nature of the book as a collection of self-contained short stories and photographs meant that we were also able to release sections on outlets such as Playboy leading up to our release date.

To successfully execute our vision and maintain ownership over our product, Andrea and I established our own media company, Virgin Twins, working in association with our co-publisher Impulse [b:], financing the printed book ourselves through crowdfunding. This allowed us to create exactly the product we wanted without artistic compromise. Raising over $21,000 through our Kickstarter campaign gave us the leverage to create a beautifully printed book with a guaranteed audience on the other end, without the financial risk of fronting the production costs ourselves. This felt like a very modern publishing process, and was a dream for us to be able to create our book on our own terms.

Andrea, tell me a bit about your fascination with antiquity, with goddesses and myth. A lot of sex work writers these days are sort of post-modern memoirists, using social media, film and audio, performance, even the new journalism idea of immersing yourself in an underground. What about the classics resonates with the story you wanted to tell about your own experiences?

AW: I am a story nerd. I studied literature and religion in university because I think the only thing that separates fiction from doctrine is belief. What is the line between the stories we read for fun and the stories for which we will kill? Myth exists at the intersection of folk tale and religion, and the monomyth, or the hero’s journey, is at the core of every single story that we tell. I am naturally drawn to the work of Joseph Campbell and endeavoured to structure Modern Whore with the monomyth in mind: from hearing the call to whoredom and refusing it, to entering the sex industry and overcoming a few of its many obstacles, to re-entering the land of the living with the ultimate treasure, which I see as the book itself. Though I relied on Campbell’s monomyth structure, I found it lacking in telling my particularly female story, since heroes are traditionally men and certainly not sex workers. The myth of Persephone has always resonated with me as a uniquely feminine sojourn into the underworld because it deals with mother-daughter dynamics, rape, power and victimhood, as well as reunion, and the reconciliation of two seemingly disparate parts within oneself. By relying on the timeless structure of the Persephone myth, I not only sought to make Modern Whore a modern heroine’s journey, but to transform a universal victim into her rightful position as hero.

Sex work also has a particularly mythic beginning as it is posited to have begun in temples dedicated to the goddess of love in several different cultures many thousands of years ago. I am highly indebted to Nancy Qualls-Corbett for her book, The Sacred Prostitute: Eternal Aspect of the Divine as a soul-enriching source of historical and mythological criticism that probes a time in human history before male-dominated monotheism established sexuality as the antithesis of spirituality.

Nicole, tell me about the process of conceiving and executing these photo shoots. Some of them are visual puns, others seem to literally illustrate the text, and some are just voluptuous portraits of Andrea/Mary Ann. What role do you imagine they play in someone reading her prose and learning about her story, especially with its themes of asserting agency within something many people see as objectification?

NB: Confronting the negative and judgmental assumptions placed on women who express their sexuality overtly is an essential component of our work. The tension between what is revealed or hidden is a predominant theme of Modern Whore which manifests in the erotically charged visuals. Andrea hid her work from her family and friends, and her real name and identity from her clients, which is of course a contrast to the fact that they were experiencing her naked body and various degrees of emotional intimacy while not penetrating her full identity.

A key reference for the photography was our treasured collection of ‘60s-’70s era Playboy magazines. Andrea and I both love poring over the issues from that era, which feature sumptuous film photography of bunnies that confidently meet the gaze of the viewer and are connected with their own sexuality amidst a beautiful aesthetic. Though magnificent, the women featured were permitted to communicate only through their bodies, or through laughably cheesy playmate interviews, and women in general were rarely granted intellectual space within the magazine. We wanted to create another take on the way erotica exists in mainstream society: with more agency from female creatives, inviting the gaze of viewers from all genders for both pleasure and mental stimulation. Ultimately, we as a society are understanding that the story behind the creation of a work of art—and whether the model herself feels exploited—is important, and that must be considered when we assess imagery that is seen as objectifying.

As a photographer, I’d like to be an antidote to the Terry Richardsons of the world. I think that part of feminism is a woman’s right to safely express her own sexuality, and the creepy-uncle-Terry dynamic of the predatory photographer must be abolished. It was paramount to me that when conceiving and executing the photoshoots for the book, Andrea and I were working from a shared vision for what we wanted to achieve visually. That included how she was being represented, and how those images lend to the storytelling and the sensory experience of the narrative. I think photography was important to this project because there’s an inherent desire to look at the author of this memoir, and to experience her performing as the various aspects of the Mary Ann/Andrea personae—from the grotesque, to the humorous, to the arousing. With the images, I wanted to explore the male gaze, which was the primary observer of Mary Ann the escort. Similarly, I wanted to bait the male gaze through the voluptuous portraits in the book, while also satirizing it, and re-claiming it as my own gaze on Andrea, and she on herself.

We also wanted to evoke the spirit of erotica photographer Bunny Yeager in her '50s-'60s era heyday, who famously captured playful pinups of Bettie Page through their creative partnership. Similarly, since Andrea and I are close friends who love playing around with each other, the intimacy of the photography is a reflection of our relationship and our comfort level with each other.

Which images do you feel are “Mary Ann,” which are Andrea, and which are another character entirely? Persona is a crucial part of Andrea's work, so what was it like for her to put on those personas for her friend, not a client?

AW: It’s definitely a mix. I feel like I play Andrea in, say, “Unshameable Love,” the story about me coming out to my parents, accompanied by Nicole’s candid shot of me calling my mother with the lights of Zanzibar, a famous Toronto strip club, reflected in the shine of my eyes. I play Antagonist Andrea in “The Merry Men of Mary Ann,” the husband fucker with a man’s ring finger in her mouth, eyes straight at the camera. (The hand belongs to our co-publisher, Eldon Garnet of Impulse [b:], which we thought quite fitting.)

The photos of “Touched” are of Andrea as Wet T-Shirt Model for Nicole. We shot at Hanlan’s Point on Toronto Island, a clothing-optional beach, when I saw a man on his towel in the sand dunes jerking off. “Err, Nicole,” I said as she continued to shoot below me, “There’s a man over there watching us and masturbating.” I looked over again. He waved. I waved back. We kept shooting. The resulting picture is not of Mary Ann, but perhaps of an Andrea that doesn’t give a fuck if people are looking at her or her pictures and yanking their chains. To each their own. When we were finished, the guy, late-40s and probably wearing a toupee, came over to us and asked us out to lunch. We kindly rejected his offer. “C’mon! I’ll pay for it!” he said. No thanks.

“A Whore’s Last Words” is probably the closest set to Andrea the Person, specifically in her guise as Andrea the Organic Farm Intern, considering the shots were taken in the last month of my second year working at a farm post-escorting. I relished gluing those long, press-on nails to my filthy farm fingertips. From being perennially dirty to getting dolled-up, donning the finest pieces scrounged from the local Value Village, and posing for the camera at the farm, the process was so deliciously foreign by that point that I truly did savour every moment of modelling for Nicole that day.

Other photos feel bigger than Andrea or Mary Ann: in “Tyrant,” I channel my inner superhero (superwhoro?) as the streetwalking woman in red, the mama bird watching the world from her nest. In “You Look Like a Movie Star,” I am my most idealized and archetypal self; I see myself in the main photo not as a woman but as a volcano, erupting with erotic femininity. It is, in my opinion, the hottest photo in the book. The series that follows is an epic amplification of Mary Ann, Andrea, and a Sex Goddess. I’d be lying if I said I was that glamourous in real life. Andrea pants more than she moans in cowgirl. “Go Leafs Go!” is an example of Andrea washing off the stink of Mary Ann after a night of not-so-pleasurable work. I am nude, but I am not sexy, and none of this is for sale.

While shooting with Nicole was almost always a fun, creative endeavor, modeling for “Go Leafs Go!” took me back to a dark place. During the shoot, I was hungry and sleep-deprived, tired from shooting the marathon of “Movie Star” photos in Nicole’s bedroom. We set up in her washroom, and I wanted to go home. My breasts in the photo have a natural, weary hang to them. I, too, felt droopy. I thought about all those nights I was exhausted after work, specifically the night I slept with a lazy, stinky, man-boy in the basement of his dead parents’ suburban bungalow, of all the things I’d done for money for which I should’ve been paid more. The shot itself is vulnerable. The difference between Nicole and a John is that I trust my collaborator and close friend to not exploit me; no matter how nice a client is, I can never fully trust him with my vulnerability. Performing for Nicole builds a book and an artistic partnership; performing for a client satisfies his needs and pays my bills. Whether I perform for art or for pay (or both), I always put my fullest self into whatever I do. I am also 98 percent certain Nicole respects me, but with a client, it’s hard to be sure.

NB: To me, the images are always Andrea, but representing various aspects of her experiences, other people’s impressions of her, and her own imagination. Andrea is a versatile performer and has the ability to act as a chameleon, transforming herself throughout all of the various tones and aesthetics of the photography. She’s also exceptionally daring and game for just about anything to get a great shot, which gave me lots of freedom to play with where we took the imagery. The constant things, visually, are that Andrea appears in each photograph and they are all shot on film. In that way, the visual component of the memoir is meant to feel like cinematic film stills of various genres in which Andrea performs characters ranging from herself, herself as Mary Ann, and herself in collaboration with women from pop culture.

“A Whore’s First Words” and the centerfold were both influenced by Britney Spears as baby-whore inspo, and secondly in her Cindy Sherman-inspired 1999 Rolling Stone cover. We replaced the house phone for a smartphone, and the Teletubby with the whore’s essentials: condoms, lube, and a faux-fancy purse. We borrowed from the image of both Kim Kardashian and Stephen King’s Carrie to construct “Holy Ho,” adding a bit of Virgin Mary to taste. The opulent, sex-drunk “Gifts” is directly inspired by Marilyn Monroe, and the “Reviews,” in reaction to a recurring comparison on the review boards, by Mary Tyler Moore. For “Tyrant,” a fictional story from the perspective of a cat-caller, the photoshoot veered into documentary. Andrea was dolled up in a '90s-supermodel themed ensemble with a short red dress, smokey eyes and flowing long hair. She stomped down Yonge Street and I captured the reactions of various men who stopped to stare.

A key theme of Modern Whore is that complexity of human identity—not being misled into thinking that prostitution is a black-and-white issue or experience. It’s about seeing the nuance and individuality in the personal experience and understanding the humanity there. That’s why I think seeing Andrea throughout the book is important, and hopefully as a friend I can use the intimacy that I have with her to give the audience a window into her many facets.