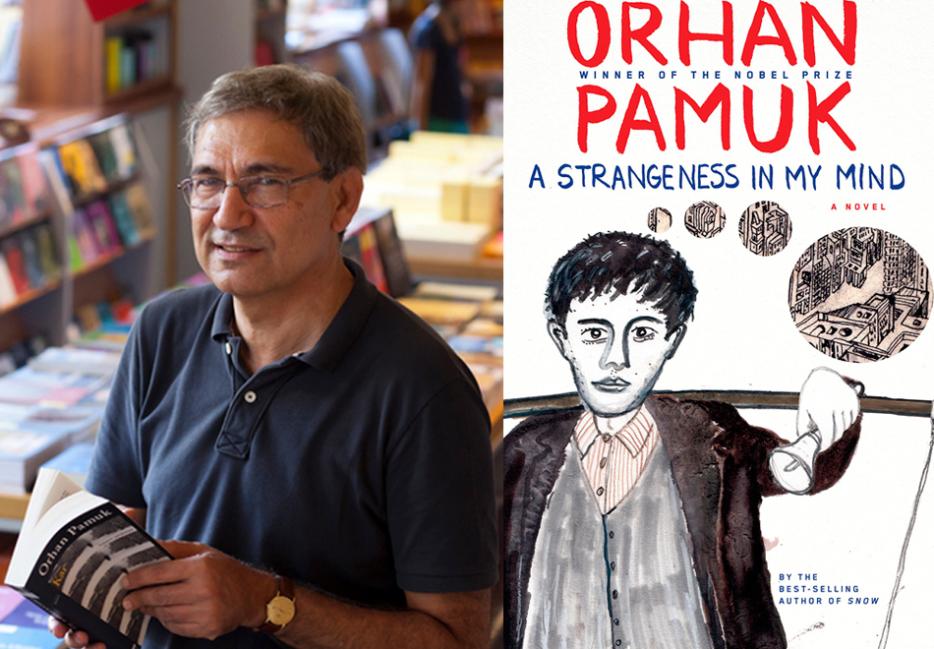

Orhan Pamuk knows many things about cities. He’s written a book about the city he calls home, 2005’s Istanbul: Memories and the City, and offers another perspective on the same place in his latest book, the sprawling novel A Strangeness in My Mind. While its scope is vast, incorporating over forty years’ worth of history, its focus is humble: Melvut, the novel’s protagonist, moves to the city from a rural area at a young age, and goes on to make his living largely as a food vendor. This includes time spent selling yogurt and boza, a fermented beverage that, in Pamuk’s telling, takes on a deeper cultural significance.

It’s through Melvut that Pamuk can explore a number of facets of the city, and it’s through his perspective that he’s able to chronicle the way that it changes. “[W]hen he comes to Istanbul first, he also sees old wooden buildings and new three-story buildings that replace wooden ones, and even six-story-high ones, where you can shout and the top-floor guy would hear you,” Pamuk said as we spoke in his New York apartment. (Pamuk spends part of the year there, while teaching at Columbia University.)

Our conversation encompassed the process behind A Strangeness in My Mind, questions of how novelists deal with food and eating in their work, and how Pamuk’s own work establishing a museum has affected the way he interacts with cities around the world.

*

Your new novel left me with an incredible sense of the city in which it’s set, and the way that cities and buildings can change over time. You studied architecture when you were younger—do you feel like that’s affected you as a writer?

Yes. I care about urbanism, and I have an interest in architectural composition, especially architecture with an urban stress.

How did you settle on food as the central occupation of the protagonist?

There are two kinds of writers: melodramatic writers, dramatic writers; funny writers, serious writers; and so on. There’s one distinction that I always make: the writers who talk about and write about food with relish, and writers who don’t mention it. You can’t see any food in Dostoevsky, while Thomas Mann enjoys going into the details of food. I am that kind of writer. I like talking about food, first of all. Second, and primarily, I made my protagonist a street vendor. Eighty percent of vendors in the last eighty years are selling yogurt. My character sells yogurt, ice cream, boza, chicken with rice, and so forth.

Are there similarities between the food sold by street vendors in Istanbul and the street food culture you see in cities such as New York?

There is not one essential thing. When I chronicled my character selling yogurt in the 1970s, yogurt was not even a bottled product. Then it was bottled. Then came sanitation measures and government controls. Municipal control slowly came. In the 2010s, in the book, then you could compare it to New York. In the 1960s and 1970s, it could not be compared to the New York of today. But then, perhaps, all towns are changing; government control came in these forty years. And the novel suggests that military coups and military discipline are imposed, there are demands and restrictions, especially over street vendors, those that sell food.

That reminds me of the way that politics slowly make themselves felt over the course of the novel. I’m thinking in particular about the scene in which Melvut’s cart is impounded. Did you know from the outset that you would be introducing politics into the novel in this fashion?

Melvut spends forty years in Istanbul selling things, gets mixed up with politics, but he is not a political man, in the sense that he thinks he has a mission, nor is he a militant. He has political ideas, but they are soft. He has radical, liberal, left-wing friends, even socialist friends, and he has radical, nationalist, political, Islamist friends. The fact that he doesn’t have strong political and moral ideas helped me, so that he can go to all corners of Istanbul society without much of a problem.

Throughout the novel, you have a number of first-person voices interwoven with the main third-person narrative, which reminded me of your work in My Name is Red. When did you decide to take this approach?

Actually, I started this novel as a short novel. Then I realized that, for a street vendor, you have to explain what a street vendor is, and it began to address that epic energy in me. Most street vendors were living in shantyhouses, they were migrants for poor parts of Turkey—it’s a very typical story. Not just a Turkish story, not only an Asian story, but a global story. These characters are always represented in modern and classical literature as background characters, whose humanity is not explored and developed.

My initial idea was to write about a lower-class person, expounding his full humanity. I began the novel, and it began to get longer. I did a lot of research; I talked with many, many street vendors. The trick is that, first you eat something, and then you start a conversation, and if the guy is forthcoming, you tell the guy who you are. Sometimes university graduates were helping me. I gathered so much interesting [information] from all those sources, really, on the textures of city life in Istanbul, that the novel was getting bigger, like a 19th-century Dickens novel. I wanted to represent the authenticity, the colors of these first person singular characters who were telling how they built their house, what they do, how they cook the food in the street, how they ran away from police, the little tricky things they do to cheat, and so forth.

Also, I wanted to write in a very direct way that the women are so oppressed in their daily lives. How they all manage, from cooking to caring about children, from buying things from the street to handling family budgets. While they do all of this for their fathers, their husbands, their husbands’ fathers, their children—they’re all so oppressed that most of the time, they don’t even like going out from the house.

What was your first exposure to boza?

Boza, as I describe in the book, was a very romantic beverage in my childhood. We enjoyed it, not for the taste of it, but more for the ritual of it. In the middle of cold winter nights, a boza seller walks down the streets. It’s a slightly fermented alcoholic beverage. Ottomans enjoyed it because it legitimized having some beer—something slightly alcoholic, and never thinking that there’s alcohol in it. For me, in my childhood, in liking this poor guy who was also wearing these peasant-like clothes and who was shouting, “Boza!”—this reminds us of old Ottoman times. I used to do this in the 1950s and ’60s, with my grandmother, with our family, just like in the book—“Come up, come up!” This, we used to do.

Forty years later, when I did research for this book, I learned that boza vendors are also aware of the fact that most of the buyers are not buying for the taste of it, but for the ritual of it, in getting associated with something traditional, that belongs to good old Ottoman times. At the heart of the novel, there are all these miniature discussions of identity, belonging, continuity, what is past, the moral responsibility to preserve the past, whether national identities come from religion. These are darling things to me that I explore in my other novels as well. It seemed perfect for me to dramatize this slightly alcoholic beverage and explore with the reader the romantic vision of old Ottoman times contrasted with a fast, booming economy and the individualism of chaotic city life. These are the contending elements of the novel.

As someone unfamiliar with boza, I was really struck with how it seems to evade description early on—is it sweet or sour?

It’s not the taste of it that counts. It triggers so many social contradictions; it has so much symbolic value for my character. In the end, it’s not the taste of the thing. It’s controversial.

When you were talking through the city doing research for this novel, what did you notice had changed the most?

I walk in the city all the time. It’s not because of research; it’s a lifestyle. I like it. I belong to that city every time. You walk around to see your friends, to see your publisher, you go to an exhibition. I like my city. I belong there. The saddest thing would be to be cut away from it. I’ve lived all my life in Istanbul. Yes, I’ve had some bad political times and am now teaching at Columbia—I got this job eight years ago because I was pressured too much in Turkey. I’m happy spending one semester here because of all the tension, living with a bodyguard, the political tension—I get a little bit of a break here. I also like the museums and bookshops in New York. It’s relaxing.

Do you also do a lot of exploring of other cities on foot?

Exploring other cities as a tourist—I like that. And since I made a museum, the Museum of Innocence, I am also determined to go to every single possible museum in a new city.

Melvut is the only character whose first-person perspective we don’t get over the course of the book. Did you have that planned out from the beginning of your process?

Yes. The challenge was to write about a lower-class character but make his individuality like in Hamlet or The Brothers Karamazov—to construct him as a full character. For me, writing a novel, all these little details are not decided at the beginning. You write a novel, you start from a corner, you develop it. You have new ideas and change, new ideas and change. It’s like a painting or a drawing. I wanted to make my character distinct from others. Underline his solitary nature, his solitary and good, well-meaning nature, and also to lend him some part of my mind—that was essential.

In my childhood, and also my teenage years and my twenties, all of my friends used to tell me, “Orhan, you have a strange mind, do you know?” And one day, I read William Wordsworth’s poetry, and I thought, I’ll use this in a book one day. This is that book, in the sense that I wanted to explore and fully develop the visions of a lower-class person who is walking in the street all the time. Then we see that he has a family; then we see that he came to the city and built his house with his father. Then we see that he isn’t as lucky as his cousins, who are good in the construction business, while he’s selling food. And so forth, and so on. All of these ironies that I like.

A novel, for me, is an excuse to pin down, collect, and put together all the little things about daily life that I like writing about. A novel is an excuse to, just like a museum, preserve the details, colors, tastes, social relationships, rituals, advertisements, smells, the chaotic richness and the sentiments that that richness lends us in the city. I’m not saying these are essential attributes and details of Istanbul. All the galaxy of details that my protagonist Melvut takes us through, perhaps will pass away. It makes me preserve and write about them. The novel has an unsympathetic side to daily life in Istanbul. I am this kind of person; this is the way I am. I am happy to preserve all these details and put them in one strong story.

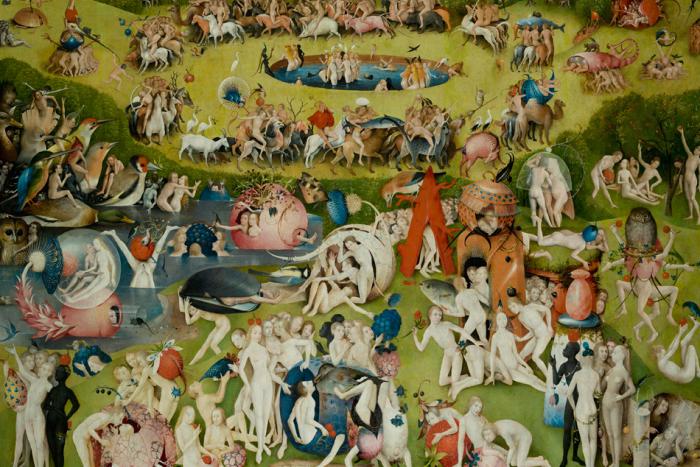

Is that same impulse where the illustration in the religious newspaper that Melvut becomes fascinated with comes from?

That picture is first associated with the fact that Melvut some conservative characteristics. But it’s not based on religion; it’s based on looking at old things. His imagination invents mysteries and sees shadows and mysterious, strange things that remind him of the stories that he listened to in his childhood. That picture is a part of that discussion in the book, whether our identities come from the restrictions of religion, or a romanticized understanding of the past is more important than that. But don’t think I write my books with a program like this. I found, just like James Boswell, my own humors. I write and edit sometimes with the tip of my pen, just doing. A novel is poetic inspiration that comes from nowhere, and is not calculated. There’s also the calculation of the plot, the framing, the shaping, a little bit of experimentalism, a little bit of traditional 19th-century novel—all of that went into the making of this novel.