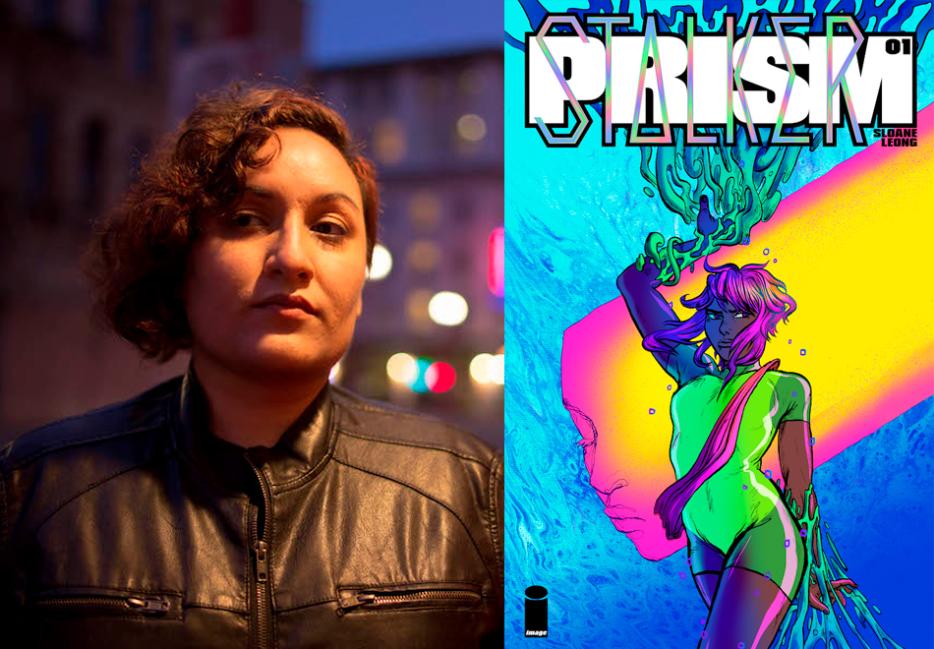

Sloane Leong’s Prism Stalker, a new series from Image Comics, begins inside a dream: Human forms abstracted by swirls of creamy pink and radioactive orange. This is how the young protagonist Vep remembers her home—a planet ruined by plague. Her people were rescued by a galactic power known as the Chorus, which recruits them into service with the empire. Vep ends up at a telepathic police academy, training to put down indigenous unrest. Struggling to master her native language, manipulated into complicity, Vep’s disquiet reveals itself during psychic combat; fellow students watch their bodies liquefy or crack apart, fighting through illusions. The moral corrosion of colonialism makes everything slippery. One of Vep’s teachers takes hold of an ancestral necklace, not without tenderness, and then tears it from her neck: “A distraction you can’t afford here.”

Before creating her current project, Leong put in time contributing art to various other comics, including Dial H, an uncommonly strange DC monthly written by the Marxist-surrealist China Mieville. Prism Stalker is the first series she owns, in more than one sense; Leong scripts, pencils, and colours each issue herself. For all its overlapping textures, its membranes and trellises, she draws this world with loose ease.

*

Chris Randle: On your website you describe yourself as a "self-taught" cartoonist, so it felt irresistible to ask: what did you learn from?

Sloane Leong: Reading books, reading comics, watching movies and stuff, just absorbing what I saw. I didn't have any formal training. I think I took an art class when I was in, like, third grade, where I learned how to finger-paint beach scenes, which was fun, but nothing beyond that [laughs].

You're from Hawaii...was that helpful in itself? The fact that you didn't grow up in some random suburbs?

Yeah, I was born in southern California, so I went to school there for a little bit, then I lived in Hawaii, and that was when I was really starting to come into my own as an artist, painting and stuff. The art scene in Hawaii specifically on Maui was pretty much whale art and beach photography, and beyond that there was really nothing. I was absorbing other more interesting stuff on my own on the Internet, like roleplaying on forums and reading webcomics and fanfic on the internet.

How did you first get into work-for-hire comics?

The first thing that got published, I think I was 18, and I did a two-page comic for Slave Labor Graphics, for an anthology called Fat Chunk: Robot. I don't think they exist anymore. Did they fold? [laughs]

And they published, like, Johnny the Homicidal Maniac, right?

Yup. Yeah. I didn't really grow up reading comics, I started reading them around 14, so I didn't really have any history or know who published what. But I used to draw for a website called EnterVoid, I don't know if you've heard of it. A lot of Canadian cartoonists were on there, like James Stokoe and Marley Zarcone. Basically you'd make an original character, you'd do a design sheet, and then you would pit your character against another person's character, and you'd have to draw a short comic with them fighting it out. You'd get graded on skill, creativity, and technique, and people would rate you from 1-10, and they'd also do long critiques. It was really brutal [laughs], because there were teens like me going up against 30-year-olds. It was intense but fun, and you could do something short like a five-page comic within two weeks, or they'd have tournaments, and you'd have to draw a 22-page comic within two weeks, with a month's worth of fights. That was formative for me as a cartoonist.

Prism Stalker began as a novel, right?

Yeah. It was a baby novel, and then I wanted to do a visual novel, like an RPG game, but it was too complicated because I didn't have any experience with gaming. And then after several years I felt confident enough to draw it, so I settled on doing a comic.

Do you write detailed scripts for yourself, or just lay out each issue first as thumbnails?

Mostly outlines. I'll compile an issue's worth of scenes and ideas, but they're usually only a couple of pages long. I don't write dialogue until I'm actually drawing—as I'm drawing it, I'll be thinking through dialogue and writing it down. To me the characters are super amorphous, and when I start drawing a scene I'll be like, "Actually they wouldn't say this, and they wouldn't act like this." Or the way I intuitively draw them acting out their emotions will alter how I think they should speak, what they're thinking. So I don't plan until I'm in the mix drawing it. I do have a loose overarching storyline, but I don't like going into too much detail, because it kills the momentum for me.

It is funny that Prism Stalker started as a novel, because the story most reminds me of this species of psychosomatic '70s science fiction—I was thinking of writers like Samuel Delany, Octavia Butler. Was that in the back of your mind?

Oh, totally. I think the most apparent inspiration is Sailor Moon, magical girls shouting out moves, and I wanted to take that and—not dissect it, but elaborate on it, instead of just being like "this is my water attack." There's one move, I think in the fifth issue that I just drew, it's this frog alien and her move is forcing someone to experience what it's like to give birth to hatchlings from their back [laughs]. That's like her psychic move and it's very traumatizing if you're not a frog alien. I just try to take that idea of transmitting an experience and go really weird with it.

That made me think of—Dan O'Bannon, who wrote the screenplay for Alien and came up with the basic concept and everything, he had Crohn's disease, and I think he understandably had a lot of frustration and trauma surrounding that. So he was like, my idea for this horror story is, what if men got impregnated?

Because that's what it feels like, yeah. Body horror is a big thing for me. I have chronic [gastrointestinal] disease, so every time I eat I get nauseous and sick, it's been happening since I was a tween. So I have this disgust and—not complete fear, but a dread-filled fascination with my body, because I'm not in control of it, and I've had cancer scares and stuff. Asthma. The body is so crazy, in how it can turn on itself. That's a big inspiration for the entire world [of Prism Stalker].

That is such a recurring theme with Delany and Butler as well, this fantasy of the mutable body. You did a minicomic about it, but there's multiple scenes in Prism Stalker—I was thinking of the one where Vep becomes this membrane of frantic lines. I love that part. And it doesn't feel clean or sterile like a lot of clichéd science fiction, the aesthetic is techno-organic. All these giant hives. People pressing into the flesh of a door to open it. And the palette is so tropical. Were you consciously trying to go against all those clichés?

Yeah. And I feel like that's my perspective on a radical future, a biological synchronicity between us and our environment. Acknowledging it as something that's alive, although not necessarily conscious, which comes from my native Hawaiian background, having that relationship with the land you're on. So I wanted to do a sci-fi version that was a little more flashy and colorful. I just love how dynamic the human body is on a cellular level, how it can encode data into itself.

I feel like a lot of bad science fiction is about overcoming or erasing nature, rather than reshaping it, so that was cool to see. Another thing that struck me was...this is a story about a refugee who's been displaced by a terrorist attack, and ends up working for a private military contractor, but it doesn't feel clumsily allegorical. How did you go about gesturing towards these political ideas, but in a way that's—

—not too reductive?

Yeah. That reveals the operations of colonialism by displacing it into a different context.

I drew a lot from Hawaiian history and culture around the 1890s, when Sanford Dole and other businessmen came to Hawaii to start plantations for sugar and pineapples. There were all these immigrants coming in to work for them, and the natives were working for them, so there were hierarchies involved. The plantation owners would also play mind games, like, they started treating the Japanese really well, to make them feel above the others, above the Chinese workers, above the Hawaiians. It's very messy, you know? Obviously there's oppressive subjugation of the native peoples, of the immigrants, but there's also the colonized people enacting that violence against each other. And I wanted to explore that, so it wasn't such a clean, “here's the oppressor, and here's the victim.” In Prism Stalker's world there's the Chorus, which denotes that they're going for harmony. They feel that they have the right to subjugate people for their own good. When they rescue Vep's people from that terrorist attack on their home planet, it's not like they're forcing them to leave, they're saving them from this horrible disease that's spreading. But there's still trauma involved for them.

There's this trope in shitty space-opera movies where the bad guys are so ridiculously evil-looking. And I can appreciate the camp of a villain slinking around his fabulously appointed lair, but that is not how these empires saw themselves in real life, they thought they were doing good. I loved how you capture the euphemisms they use: "It's important for your social health to move beyond your base traditions."

All the teachers are different species and races and ethnicities as well, so a lot of them also had to give up their traditions in order to take on authoritative roles at this academy for the Chorus. They're sympathetic, but they want to succeed in this place where they've found themselves.

I think of you as somebody who watches a lot of films, and studies—mm, that sounds bad, [pompously] "studies cinema." But you write about it really well. How has that informed your cartooning?

Hmm...I feel like it's such a core part of how I learned storytelling, just because I don’t have any formal training besides reading books with titles like How to Draw Comics. I just kind of absorbed media willy-nilly. Movies specifically...I think color and atmosphere was a big thing for me. I don't know, because I feel like my compositions aren't especially cinematic, I don't rely on three-panel wide shots, you know? That doesn't really come into my mind, but the color and atmosphere and mood that movies can achieve, that is present in my mind when I'm coloring.

A lot of comics that are colored, as opposed to black and white, it almost feels pointless. It's such a boring, realist use of color, compared to a movie like Black Narcissus, where it's so florid...is that what your approach is going for?

It depends on the scene. Like, a lot of the fight scenes I end up going more abstract, especially because there's a lot of psychic abstraction happening in the scene. I'm always trying to find the simplest way to depict something. Not that it'll lack detail, but if I can get away with adding a wash of color to show depth, or wash a whole scene in a very limited palette to control pacing, I'll do that. I'm always trying to use color to make the story and mood clearer.

And you even have soundtracks for Prism Stalker.

I got the idea from my friend Porpentine, who does Twine games and fiction writing, and Riley collaborates with her a lot, does music for her games. I thought that might be cool, especially because Prism Stalker has a lot of...it's a very noisy world to me. Everything is goopy and membranous and echoing. There's large chambers, crowds of people.

Do you have the whole thing planned out right now in your head? Like, do you know how long it's going to run for, what the arc of the story is...

Yeah, I have a loose outline, and I pitched it as 25 issues. I thought that was a safe bet. I feel like a lot of Image comics fail when they do that, like, "I'm just going to go on until it's canceled." 25 issues, five trade paperbacks, that seems safe [laughs] ... I think it's also my history with short comics, like, I love doing short fiction and minicomics, one-shot stories, so having something that's ongoing, to me that just means I don't have a pointed theme in mind, and that I'm groping for something to knead it to. [Prism Stalker] is such a clear experience that I'm picking apart that I have an end in mind.

Plus you're doing literally everything on this comic yourself, so I imagine you don't have much time to draw other stuff.

I'm also working on a graphic novel, I don't recommend it [laughs].

What can you tell me about that book?

It's called A Map to the Sun, it's halfway inked, it's about five girls that get forced together to join a basketball team. They're in 10th grade. It takes place in an ambiguous Los Angeles / San Diego-adjacent neighborhood, there's school drama, lots of basketball rivalries. I wanted it to be kind of like Slam Dunk, but there's a hard page count that I can't go past, like, 320 pages, so I can't do a 100-page-long basketball game [laughs]. I'm trying to condense that sort of complex, detailed drama of being a player in a game.

Is it also jarring to go from this surreal science fiction to a realist—

Yeah. I try to stay looser for A Map to the Sun, especially the backgrounds, it's more brush-y, because I just don't like drawing cars and houses that much, but that and Prism Stalker are both very kinetic, they have a lot to do with the characters' bodies and becoming skilled at a certain thing.

I have to ask, because you're doing a book-length comic about L.A.: Have you seen Los Angeles Plays Itself?

No, I haven't!

It's this three-hour-long film essay about the depiction of Los Angeles in cinema, and the director quotes from dozens and dozens of other movies with narration over that...he talks about how, in classical Hollywood, they couldn't actually shoot movies in China or wherever, they almost never had the budget for that kind of thing, so they would just pretend that these fields outside the city were rice paddies. There's a section where he's showing an old crime thriller supposedly set in Chicago, and the guy is escaping through these hog pens, and the narrator deadpans: "But what about those palm trees?"

I did say [A Map to the Sun] is set in Los Angeles, but because it's not "sexy" like L.A. is, I try not to necessarily reference that aspect. I'm mostly referencing, like, the hot, semi-tropical desert property there. I don't know, there's such a specific idyllic feeling, but it can also be really gritty and ugly.