The best way to hypnotize a chicken is to tuck its head under its own wing, thereby mimicking the posture of sleep. Rock the chicken back and forth and gently set it on its feet. The record for sustaining a hypnotic trance in a chicken, according to H. B. Gibson (author of Hypnosis: Its Nature and Therapeutic Uses, 1977), is three hours and 47 minutes. In 1996, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl told Stern magazine that he had once hypnotized a chicken by holding its head to the ground and drawing a chalk line outward from the beak, a technique favoured by filmmaker Werner Herzog, who claims to have hypnotized chickens in at least two of his films: Signs of Life and The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser.

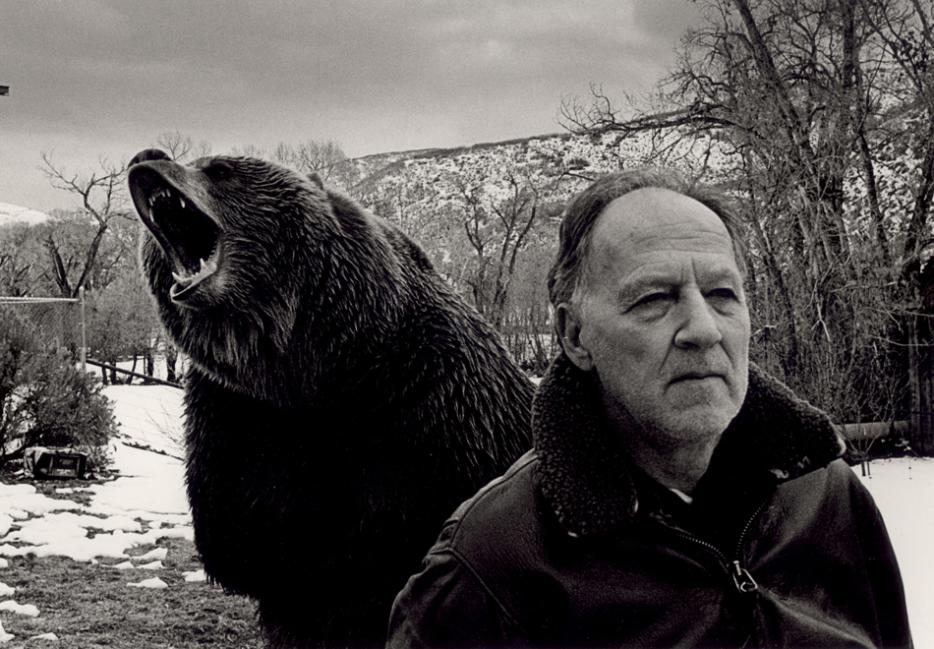

“The enormity of their stupidity,” says Herzog, of chickens, “is just overwhelming... they frighten me more than any other animal.” This is vintage Herzog: the carnival trick as gateway to anxiety and horror. And one imagines the lightbulb going off over his head: if it works for chickens, why not actors? In 1976 he made Heart of Glass, a film in which most of the characters appear to be lost in trance, which they are, since Herzog himself hypnotized his actors before every scene.

“The reasons for doing this experiment,” he says, in a behind-the-scenes book about the making of Heart of Glass, called Every Night The Trees Disappear, “were simple: the story of a village community in Bavaria that walks straight into a foreseen and foretold disaster, almost like a community of sleepwalkers, needed a specific stylization.” The film is set in the early 19th century. The heart of the village is the glass factory, where the means of production haven’t changed much since the Middle Ages. The glass they make, based on a secret formula, is a beautiful ruby-red and highly valued, but one day the chief craftsman dies and takes the secret with him to the grave. The townsfolk call on a herdsman, known for his uncanny second sight, to lead them out of their dilemma and into an uncertain future, which they face, as Herzog says, as if in a pillowy dream: they are the people history is about to forget. It doesn’t end well for the village, but typical of a ‘70s Herzog film, it doesn’t end well in a breathtaking way.

To achieve his “specific stylization,” Herzog hired a professional hypnotist. The actors, many of them amateurs who answered an open casting call, were pre-hypnotized in advance of the shoot, to weed out the skeptics from those willing to play along. “I see a most lovely forest,” one woman says, interviewed by the director while under the spell, “with every sort of plant and tree and every type of bird that ever flew, and every day the trees change their places, so the forest is never the same. And every night the trees disappear altogether, and only the sleeping birds remain.” She was hired. In the end, Herzog grew tired of the professional hypnotist’s New Age mumbo-jumbo and opted to do the work himself, as he had in the past with the chickens. By all accounts he was a gentle and generous hypnotist. But every time I see the film (and I’ve seen it four times), I wonder: what if they never woke up?

I understand that, in theory, hypnosis is a benign act, no more distressing for the subject than a short nap. But I fear it as much as Werner Herzog fears chickens, because the act of ceding control to the will of another is terrifying. I figure I’d be the one who wouldn’t wake up, the hypnotist fruitlessly snapping his fingers in front of my face. I would run out my years in an institution seeing nothing more than an infinite chalk line running from my beak.

People get hypnotized for good reason, to lose weight and quit smoking. The Daily Mail reported that Kate Middleton considered hypnosis as a drug-free approach to pain relief during childbirth. “Some of her friends have used this method and swear by it,” a source told the Mail. (The palace, well aware of how the royal fuse can ignite social trends, would neither confirm nor deny the rumour.) In a medical setting it may be useful and safe, no different than the temporary scrambling of “normal” neural connections that result from pharmaceuticals. But my own appetite for neuro-scrambling is limited. Hypnosis eliminates personal context--how we recognize the shape of our lives based on the past, how we anticipate the future--and substitutes an experience delivered by a third party. My subjectivity is at stake: who am I, under hypnosis, if not someone else’s idea of me? Are my memories my own or manufactured, and how do I tell the difference?

According to Werner Herzog, hypnosis “can be practiced fairly easily,” which only makes it worse. “It is even possible to induce hypnosis without the hypnotist’s personal presence,” he says. He claims that people can be hypnotized by the images and sounds on a movie screen, or over the telephone. He toyed with the idea of building a hypnotic prologue into Heart of Glass, where he would appear on-screen and “invite” audience members into a trance. Then he would show up again at the end to wake them up. “The idea,” he admits, “was so stupid that it did not last long.” It’s an interesting marketing gimmick: people would buy tickets to Heart of Glass over and over again, never quite sure if they’d already seen it.

But perhaps Herzog realized that a low-grade hypnosis, as fostered by politics and advertising and the media, is exactly what we want to escape when we encounter art. It’s no coincidence that the former Chancellor of Germany is skilled at hypnotizing chickens: political rhetoric is a chalk line. As for my own fear, I’m afraid of the chicken-like enormity of my own susceptibility: to chalk, shiny objects, Apple products, the banal language and imagery of coercion. I prefer to at least try and stay awake. I love a Herzog film, but if ever he calls on the telephone, I’m not answering.

The Lost Library: forgotten and overlooked books, films and cultural relics from Tom Jokinen’s overstuffed Ikea bookshelves.