When he started seeing someone else, it felt like a weight had been lowered onto my chest. I knew my reaction was irrational—I mean, we weren’t even dating—but it was so unfair of him to keep rubbing it in my face. Worse, she was blond, elegant, so thin she seemed collapsible; nothing like me. Everything about her seemed interesting, better, unique. Even her eyes were two different colours.

I kept seeing them everywhere, too. They’d go to dinner or she’d accompany him to events, holding his hands, whispering in his ear, whatever little secrets they shared.

At least I wasn’t alone in feeling like this. I mean, the forums were filled with girls, mostly teenagers, who were furious and weepy and confused. Some of us had known each other online for years, trading fan-fiction and photos and clips of him shooting arrows in Lord of the Rings and (spoiler) dying in Black Hawk Down. We were Orlando Bloom’s biggest fans—who else do you think was watching every fucking installment of Pirates of the Carribbean?—and just because he was taking up with Kate Bosworth (she was in that movie, Blue Crush, about surfing and who gives a shit) did not mean we were deterred.

It sounds absurd, but the only word big enough to describe what we felt when they started dating was: devastation. We were collectively devastated.

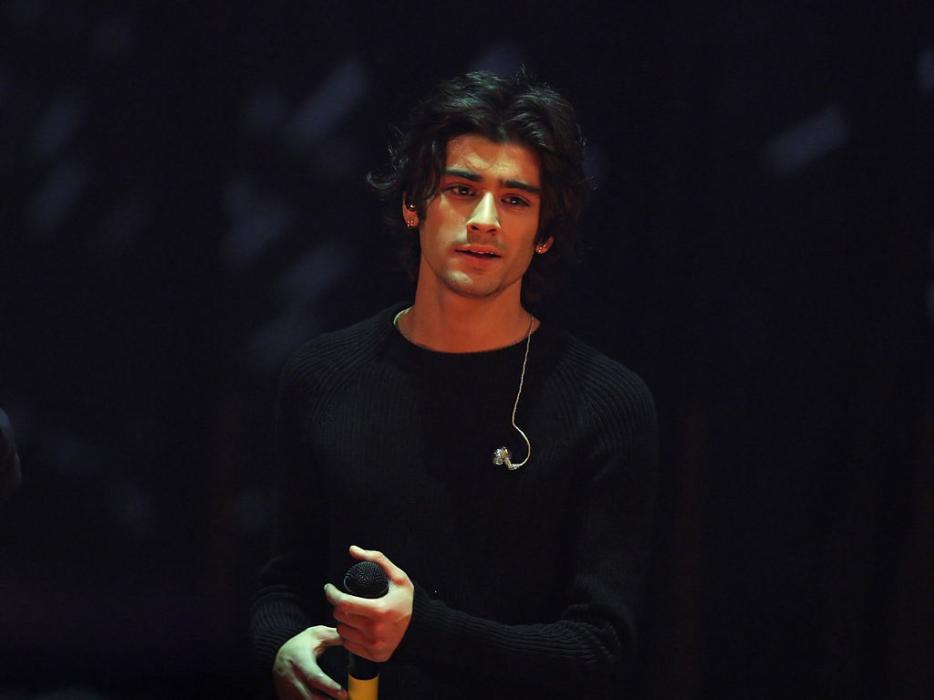

When Zayn Malik left One Direction on March 25, that same word came up: the hordes of teenage fans mourning his departure were devastated.

It’s easy to tease your garden-variety teenager about their paramour, particularly when the guy in question is a 22-year-old singer who just quit a band largely made up of deep-v t-shirts and hair goop, so that he can (probably) go solo. BuzzFeed collected reactions online, including a stream of photos and Vines where teenage girls wept over the loss. Teen Twitter was in a right state, sending Zayn angry tweets about his betrayal, harassing his fiancé Perrie Edwards for whatever role she may have had in it (Perrie is this generation’s Yoko, but white and without the fun hats), and begging the remaining 1D boys to keep it together for the rest of their tour. (Canadian band The Arkells took it a bit further, sending a joke-tweet that their lead singer, Max Kerman, would be joining 1D, leading the hordes to call it a “sick joke.”)

Teenagers, particularly teenage girls, are easy to make fun of, so it’s unsurprising that the Internet found ways to mock them for their public grief. The teenage brain is, much like a teenager, underdeveloped, frantic and hard to read: the prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning, organization, and mood, is still under construction. People know that the brain isn’t fully formed at 15. What’s curious is how intertwined a teenager becomes with an icon, someone completely out of reach but still adored.

But weren’t we all, at some point, 15, in love with someone who we’d never touch and convinced we would be destroyed by the reality of life, time and change?

Where do we get off, not taking these feelings seriously?

*

“Let me tell you, this day was a nightmare for the whole fandom.” Jane,* a 15-year-old ninth grader in Alberta, is a huge One Direction fan. “I was so heartbroken the rest of the afternoon in school.” Jane was in science class checking her phone when she found out. In a Facebook post from One Direction, Zayn said that he felt like “it is now the right time for me to leave the band” and that he was leaving “because I want to be a normal 22-year-old who is able to relax and have some private time out of the spotlight.” (The post has nearly 800,000 likes. As of now, the last comment on the post is from a teenage girl saying, “Still hurts.”) “When I got home, I cried and cried that I actually looked like I was on drugs because my eyes were so puffy and red,” Jane says. “I was an actual mess.”

After the announcement was made public, it took (this is unscientific) approximately a nano-second for a world of 1D fans to collectively lose their online shit. They begged him to stay, railed against him for leaving, and hefted even more affection upon the remaining four for sticking around. “It tore me apart once I realized he was actually gone and I’d never get to hear his high notes live,” Jane says. “I cried a river basically, and it [hurt] my heart knowing that he couldn’t handle [the fans] anymore.”

It sounds absurd, but the only word big enough to describe what we felt when they started dating was: devastation. We were collectively devastated.

Laurence Steinberg, professor of psychology at Temple University and author of Age of Opportunity: Lessons From the New Science of Adolescence, says that it isn’t so much that teens get dramatic about loss, but rather that they get dramatic about everything. “There are changes that take place in regions of the brain that regulate emotion, that tend to make adolescents more easily emotionally aroused, both negatively and positively,” he says. “Not to put too positive a spin on it, but the same propensity to get bent out of shape about something is what makes adolescents so easily happy about something too. It’s not just that the lows are lower, but the highs are higher.”

These feelings aren’t exactly the same as actual grief, but maybe closer to the fears we all have about change or abandonment. They also serve as a kind of primer for when a person starts to experience those feelings for real: the rush of falling in love, the comfort of knowing someone intimately, the gutting feeling that comes when he leaves, and the hot tears that form in the back of your throat when he doesn’t come back.

*

Allison*, a 17-year-old from Quebec, was deeply displeased with The Arkells after they joked that their lead singer would be replacing Zayn. (She refers to Max as “this guy that I have never heard of in my life.”) “It made me upset because by saying this, he was saying that Zayn wasn’t important and he could be replaced by anyone, which is false, because Zayn is really special,” she says. “That made me lose my mind. I was about to slap someone!” When he left, Allison posted a photo on Facebook of Zayn, thanking him for the good times, but also because she “wanted to show people that know me as a huge Directioner that yes, I know about the sad situation but I am not dying over this.”

That’s the thing about this particular grief: we were all privy to it because teenagers around the world were posting online about how lost they felt. On the extreme end, #cutforzayn started trending on Twitter, and if you look up the hash tag, there are still plenty of photos of tiny, bleeding wrists. Why were these girls not only expressing grief, but posting about it online? It’s called co-rumination. “Adolescents, especially adolescent girls, very frequently engage in this kind of behavior in their relationships where they are ruminating about something bad together,” Steinberg says. Social media—a portal to a literal world of teenagers who have similar interests and hatreds—only bolsters that impulse to share and connect.

Brodie Lancaster, a 25-year-old writer for Rookie based out of Melbourne, wrote an open letter to Zayn after he left. “I actively avoided clicking on any articles or videos with titles like, ‘THE MOST INSANE REACTIONS FROM 1D FANS’ because I didn’t feel like reading people with no connection to One Direction making fun of people who felt hurt, like I did,” she says.

Posting about their trauma online was a deeply cathartic experience for these girls. “The fandom is so reliant on the Internet,” Brodie says. “It makes sense that it’s also where we’d express our sadness and find comfort in one another.” Imagine if one million girls got dumped by the same guy at the same time—you wouldn’t be surprised when they all started posting tragic status updates on Facebook for at least a week.

But there’s a darker side to all that heightened emotion. “Some girls are saying #CutForZayn [on Twitter] and it made me so mad. Cutting is not something to joke about and you should NEVER self harm over something like this, or at all, really,” says Kat, one of many who started crowd funding campaigns to buy One Direction out of their contract after Zayn quit and who has personal experience with self-harming behaviour. “Being almost a year clean, I understand what it’s like to have music save your life.”

But overreaction is not only the territory of teenage girls: “It’s not like we don’t see this among adults, when sports teams lose big games,” Steinberg says. “There are a lot of adults that go online, talk about how angry they are, and how disappointed they are, and how this is going to make them in a bad mood all day. I think it’s just that in this particular case, the thing they’re upset about is something adults don’t care about. If the celebrity had adult appeal, decided to stop performing, I’m sure you’d see a fair number of adults tweeting about it too.”

But there’s another explanation for all this teenage angst, and it’s even simpler: teenagers are super into themselves.

The Personal Fable is the belief often held by adolescents that they are unique and special, the protagonist for an imaginary audience. Marc Lewis, author of Biology of Desire, says that teens often feel like they’re being observed, responded to, and judged, even when they’re not. “They think of themselves almost as a legendary character in a fable, a kind of Greek hero forging through all sorts of obstacles,” he says.

The rush of falling in love, the comfort of knowing someone intimately, the gutting feeling that comes when he leaves, and the hot tears that form in the back of your throat when he doesn’t come back.

So imagine, then, what happens to our fated hero or heroine, when the love of their life is ripped away from them without so much as a farewell, or a note, or a tweet explaining their actions. And to make it worse, to claim that you want to be a “normal 22 year old,” only to subsequently release a single with a producer named Naughty Boy. That’s a real slap in the face of our romantic lead.

“He just kind of left us hanging, and to leave in the middle of a tour and not finish it also confused me,” Sarah says. “I was a little angry that he would do such a thing and still not tweet anything about him leaving or maybe going solo. But, me being a nice person, I can’t stay mad at my idol.”

Allison is also still a fan, though she feels slighted. “He didn’t have the courage to tell us he was leaving himself,” she says. “I am slowly getting through it. The thing that hurts the most is when I listen to their music and hear Zayn sing. It hurts because I know he’s not there anymore.” In the brain of someone suffering through the loss of a pop star, it’s real. It’s as real as a breakup, something that you logically know isn’t the end of your life, but Jesus Christ, it really does feel that way, doesn’t it?

*

Being a teenage girl is hard. It’s the first stage of entry into a world that tells you that there is something wrong with you no matter what you do. You need to be thin, but not too thin, have sex, but not let anyone know, be smart, but not intimidating, be pretty, but not too aware of your good looks. And while you’re busy doing all of this, there are plenty of people telling you that the things you like are not important, or valuable, or worth having any feelings about. Teenage girls build entire fan communities around strangers and defend those strangers fiercely when attacked because they’re taught that they need to be on the defensive.

“They want people to laugh and it’s easy to laugh at teenage girls because we are more fragile, usually, so they ridicule our tastes,” Allison says. “They take the celebrities that we love and keep on criticizing them to hurt us and we have a great example in Justin Bieber. Yes, he did some shitty things but at some point, people were talking about it way too much. Some rappers did worse than that but people don’t talk about them because those rappers are loved mostly by boys.” Indeed, we give Justin Bieber a hard time for being a 20-something brat, but we seem all too ready to forgive Mike Tyson and watch him in The Hangover or on Lip Sync Battle. The difference between the two? Among a few things, one has a massive female fan-base, the other a rape conviction. But which one is ridiculed near-constantly?

It’s been a few weeks since Zayn left. The dust is settling, somewhat, though plenty of teenagers on Twitter are still angry about the loss, about what may be a run at a solo career, about the rest of the boys being stuck in a contract to finish another album as a foursome. There’s clearly ill will still festering: Zayn and former band mate Louis started sniping at each other last week.

“Sure, I’m still a little mad,” Kat says. “But is anyone really ever truly over something?” I can tell her from experience that she’ll get more and more distance the older she gets. Eventually, she’ll forget all about this until she comes back into contact with an old memory of Zayn, how comforting it was to be a part of something so much bigger than her, holding up these guys and making them what they were. She might be a little embarrassed her by zeal, but she’ll know she helped make something big.

But even then, she’ll also likely feel a deep twang in her gut: the reminder of a heart break, of a profound feeling that never entirely left in the first place. The reminder that it felt so real and so good, and anything that makes you feel that high has to end eventually. And before she even knew it, he was gone, the community started to fold, and everyone had to grow up.

I don’t think about Orlando the way that I used to, but sometimes I run into that old version of myself and it’s startling. A few months ago, I found my Orlando Bloom Fan Club notebook (long before I could make a Facebook page for him instead) and it rattled me: did I really feel this strongly? Was I really that upset over some British turd and his milquetoast personality, his unblemished skin, his strong hands, his jawline carved by the Greek gods themselves? Yes. It was real, or as real as something can be when you’re 12. And while I am now grounded, and mature, and adult, I still think Kate Bosworth is a goddamn bitch.

*Names have been changed.