Beginning in the 1950s, Gold Medal published a series of books based on classic murder trials, complete with pulp-y, sensational covers on the front and ads for United States Savings Bonds in the back. This is the first in a series of essays inspired by those titles.

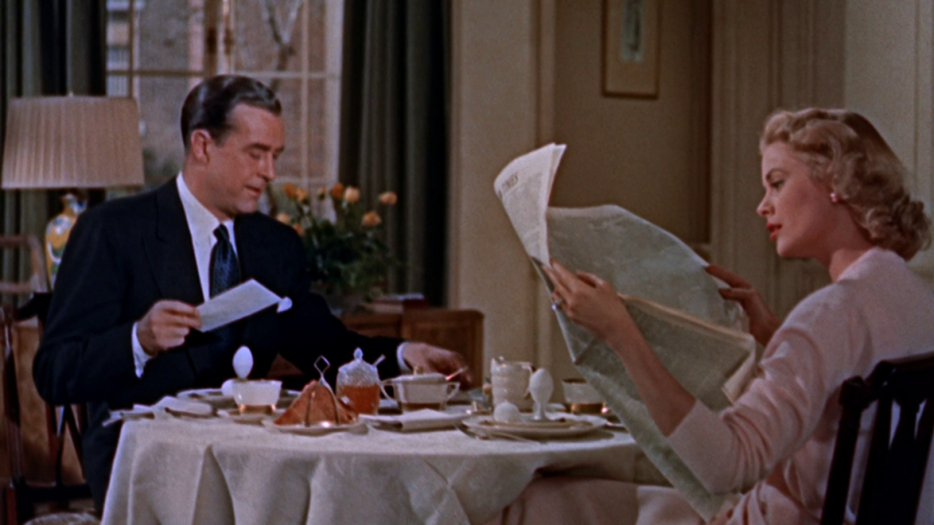

1954’s Dial M for Murder is Alfred Hitchcock’s only 3D film. The camera brings the director’s primary setting, a knickknack-filled high-class living room, to discomfiting life. After Grace Kelly kills the intruder her husband sent to strangle her, her house is activated. Objects that would prove her character’s version of events go missing, or are found in incriminating locations. The shelves, the lamps and the books stand out under Hitchcock’s camera, now animated by mute malice and potentiality. And the whole affair hinges on a misplaced key—not a key that’s lost, but one that is where it shouldn’t be. What’s captured so well in the film is the fact that murder makes the place and people around a corpse come to strange new life.

Telling the story of a crime invests all the unspoken details, motivations, and effects with potential. A murder illuminates the people in the fatal room and the society around them—who was killed, and why, and who the killer was. The key that is the killing unlocks questions that let us talk about everything else: class, sexuality, shifting ideas of perversion, all the things that a mid-century true crime book might obscure under the words “evil” or “unspeakable.”

In 1955’s The Girl in Murder Flat, novelist and columnist Mel Heimer writes about the 1943 murder of Patsy Burton Lonergan, heiress to the $7 million Burton-Bernheimer beer fortune, at the hands of her husband Wayne Lonergan in an upscale Manhattan apartment. Burton Lonergan is depicted in an off-the-shoulder nightdress on the cover of the book in which we first meet her as a corpse. This cover, and the running “The Girl” opening to all of the twelve titles in Gold Medal’s Classic Murder Trials books (The Girl in the House of Hate, The Girl in the Belfry, The Girl on the Lonely Beach, and so on) are a chilling tell of something else true crime accounts have done for a long time: they use the sexually charged murders of women, and the legal discussions and repercussions that follow the discovery of their dead bodies, to talk about contemporary society and sexuality with an openness that may not otherwise be permitted. The taint of a crime, of violence committed and a life ended, provides a way into discussions of what men do, and why.

But true crime accounts, especially ones written long after the act, can also redirect the conversation that happens around a dead body. And that’s what Mel Heimer did in The Girl In Murder Flat. The crime he writes about, the Lonergan murder, sparked an ongoing, if reductive and damning, public conversation about homosexuality and bisexuality. But twelve years after Wayne Lonergan bludgeoned his wife, Heimer skims past that conversation, compressing homosexuality into a package of “evils” in Lonergan, part of a collection of traits that naturally outflowed into a pointless murder.

*

The Girl in the Murder Flat describes, with most of the crucial details missing, a certain kind of crime of passion. Heimer’s book shows us the body first. Manhattan cops bust down the door of a bedroom and find Patsy dead, her head destroyed by brass candlesticks. After the perfunctory arrest and interrogation of an interior decorator who had joined her out dancing the night before, the police went for the prime suspect: Wayne Lonergan, the handsome Royal Canadian Air Force cadet Patsy married, separated from, and cut out of her will shortly before her murder.

When Mel Heimer discusses how the Lonergans met, his language switches from tabloid-lurid to whispering-suggestive. We get more of a sense of the actual events through what Heimer leaves out then what he chooses to write. These missing details are what everyone in New York was actually talking about when they discussed the heiress murder on Manhattan’s Beekman Hill.

Heimer gives us the dullest possible version of the story. Essentially, we get a book composed largely of scenes that would be cut from even a bad Law & Order episode. What we don’t get are the very relevant details of Wayne Lonergan’s sexual relationship with Patsy’s father, and the detailed sexual circumstances of the night when Wayne murdered his wife—Heimer distorts and omits the key elements of Wayne’s confession, seemingly in an effort to spare Patsy from an association with perceived sexual deviancy.

*

Patsy’s father, William, had been first to meet Wayne. Heimer tells us that William was known to be “sensitive,” and that his wife said that he had “other traits that are often attributed to artists.” He met Wayne Lonergan while the boy was pushing a rickshaw at the World’s Fair, and the two struck up a relationship that Heimer chooses to avoid exploring entirely, save to say that it led to the young man spending a lot of time with the rich William Burton and his daughter, Patsy. Lonergan also stopped working, presumably drawing his income from the Burton millions. When it was clear that William’s heart troubles were going to lead to an early death, Wayne focused his attentions on the young woman, securing her favour and, after the death of her father, her hand in marriage.

What Heimer suggests but avoids saying is that Wayne Lonergan was a bisexual hustler who targeted older men. As reported in the New York Times, Newsweek, and Time after Lonergan’s arrest, Wayne found his mark of a lifetime in William Burton, and quit that rickshaw job to become Burton’s frequent companion. What Heimer does tell us, long after glossing over the relationship between Patsy’s father and her future husband, is that there was something “deviant” about Wayne Lonergan.

Wayne Lonergan’s abandonment of traditional American heterosexuality is presented as having an obvious outcome: death.

But the trial and the media coverage around the Lonergan case did not omit the violent sexual details. It provided one of those key moments in which an act of evil creates a climate of permissiveness around other perceived transgressions. All of New York and its major papers found themselves allowed to discuss homosexuality and bisexuality in open, if disapproving, tones. Years later, Mel Heimer’s book puts this discussion back in the closet: like the papers, Heimer identifies Wayne Lonergan’s sexuality with his murderous evil, but unlike the papers, he stops the conversation there.

*

The papers used the circumstances of Patsy’s murder to print the first large-scale, ongoing discussion of homosexuality to hit the press in mid-century America. One of the Hearst papers published a detailed, if half-baked and sensationalistic, psychiatric view of the influence of bisexuality on character: the “deep purple threads of whispered vices whose details are unprintable and whose character in general is unknown or misunderstood by the average normal person.” Wayne Lonergan’s murder of his heiress wife allowed for a transfer of knowledge in the most disapproving terms possible, just the way Oscar Wilde’s trial had allowed the England of 1890 to talk about homosexuality—new ways of hiding and defining it, that is.

Just as the crimes of Wilde’s fictional Dorian Gray were presented in court as evidence of what “decadent” homosexual behavior was bound to, and just as Gilles de Rais’s reported homosexuality was easily equated with his penchant for child murder, Wayne Lonergan’s abandonment of traditional American heterosexuality is presented as having an obvious outcome: death. Heimer, over a decade after the crime, executes the tidy math of relating Lonergan’s sexuality to the murder: a complementary vice to his greed, anger, and lack of remorse. It becomes part of the bouquet of nastiness that allowed him to transgress to the point of murder.

In Charles Kaiser’s 1997 history The Gay Metropolis, we get the crucial detail of Lonergan’s confession, left out by Heimer and all of the contemporary newspapers: according to Wayne, he and Patsy had been in bed before the murder, and she had tried to bite his penis off during oral sex (at the time, an act firmly equated with homosexuality in the public imagination). He responded by trying to strangle her, then she began to claw him, and the fight ended with the candlestick bludgeoning.

The murder that Mel Heimer describes in detail, that candlestick bludgeoning, stands in for Wayne Lonergan’s sex acts with Patsy’s father and others, her dead body providing an easy moral endpoint to the “decadence” that surrounded her.

In Heimer’s book, heterosexual oral sex is barely hinted at. Any non-vanilla sex Lonergan had with Patsy is collapsed in with Lonergan’s “unspeakable” deviance in the suggestive portions of the confessional statement that Heimer chooses to include:

Q: Did you get much satisfaction out of living with your wife or any other woman?

A: Well, a certain amount.

Q: Did you ever make love with your wife by any other manner but by natural intercourse?

A: Yes.

Q: What was her reaction to this?

A: She did not like it and told me to do it somewhere else.

In Heimer's book, a decade after the crime and the ensuing media discussion of the sex lives of everyone involved, the immediate motivation for the crime and the complex sexual history leading up to it—the entire context and circumstances of Patsy Burton Lonergan’s murder—is avoided, glossed over, or obscured. The murder itself stands in for all of it.

*

When the 1943 papers talked about Patsy Burton’s murder, the conversation quickly turned to homosexuality and its possible link to the corrupting influence of wealth. That conversation went on so long that by the time we reach Mel Heimer’s book in 1955, her dead body has become a cypher for her husband’s sexual behaviours, for homosexuality and bisexuality itself. The murder that Mel Heimer describes in detail, that candlestick bludgeoning, stands in for Wayne Lonergan’s sex acts with Patsy’s father and others, her dead body providing an easy moral endpoint to the “decadence” that surrounded her. Heimer and his imagined audience is comfortable with the murder of a woman as the end to a story of sexual corruption: the consequence of Wayne Lonergan’s sex life is his imprisonment for the death of his wife. And, this book suggests, that murder began with his “unspeakable” sexual acts: Patsy pays the price, in this version, for Wayne’s departure from American heterosexual norms. What that departure was, specifically, Heimer isn’t going to tell us. But a violent, bludgeoning murder? He can write about that.

Patsy Lonergan died because a selfish, greedy man lost his temper and killed her because he could. In her death, she became the least talked-about aspect of a case that overtook the media for months and built on the vocabulary for queer intolerance in twentieth-century America.

The concealed key in Grace Kelly’s Dial M For Murder apartment building is her salvation when it’s found, rescuing her from imminent execution by the state. For Patsy Lonergan, it’s too late, and in Heimer’s book, her own dead body is revealed to be the concealed key. That bludgeoned, once-living form allowed writers and speakers in 1943 to address nested sexual anxieties that had gone unvoiced, to conduct a conversation about homosexuality and bisexuality on a scale that would have been impossible without this high-profile killing. In 1955, Heimer was able to take the discussions that happened around this famous case and condense them all into the single act of murder. By the time he wrote his book, Patsy Burton Lonergan’s dead body had become a lesson in what happens when men sleep with other men.