It’s never too late to try something new. From the outrageous to the mundane, Hazlitt Firsts is a collection of people doing things they’ve never done before.

I try to be the ideal audience for any movie I decide to watch. I look for the intention of the picture, and evaluate what I’m seeing according to that. This seems to be the proper way to enjoy popular art, allowing for better odds that I’ll be entertained. My fair-play attitude toward the movies was enforced, perhaps, by the childhood limitations of 13 channels of television. If you settled on a film that looked even vaguely interesting, you tried to become the person who could enjoy that movie. It was educational. Any resistance to romantic comedies en masse was successfully demolished by A&E showings of Harold and Maude and basic cable’s Sleepless in Seattle addiction.

My father’s mysterious inability to tell the difference between the box art of a regular New Release and that of a direct-to-video bit of schlock “legitimized” by a five-minute cameo from a former star cashing a cheque resulted in the family watching a lot of seriously shitty thrillers and horror movies. From those, however, it was a short walk to the aisle that held the Raimi and Coscarelli and Tobe Hooper films that deepened my appreciation for the inventiveness of great genre cinema, and came with images that matched up well with the skulls and demons on my daily high school uniform of Metallica and Sabbath t-shirts. (I also wore dress pants with these t-shirts, never jeans, but let us leave that for another humiliating confessional).

But I’ve always had one area of significant resistance in this even-handed viewing system: Bollywood.

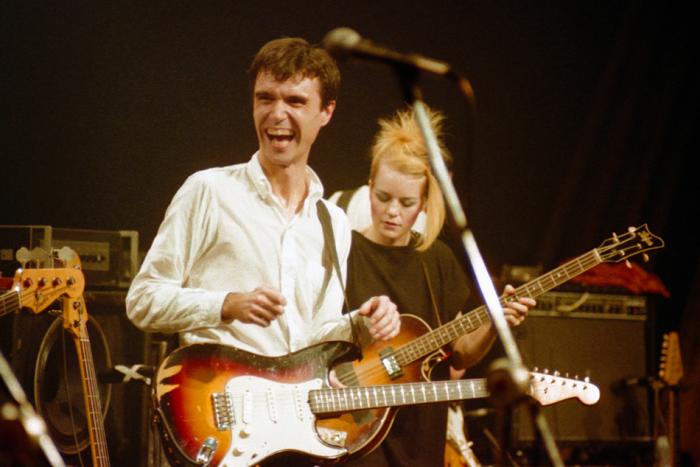

A major part of the blame for this I place on long car trips with my family, to Vancouver or Seattle or Drumheller or Calgary, during which I’d be forced to listen to an unending stream of fourth-generation copies of Lata Mangeshkar audio tapes on the car stereo, the tinny treble shrill and hiss that came from all that dubbing, and from Lata’s own plaintive high-note chops, always finding a way to cut through whatever was coming out of my Discman and into my headphones—music that matched my t-shirts, mostly, with the occasional incursion of Bowie or Eno or Aphex Twin, thanks to the influence of some friends who should have had better things to do than hang out with me.

Mangeshkar, the great playback singer star of Bollywood dating back to the ‘40s, has dubbed in the singing voices of every star from Mumtaz to Aishwarya Rai. I didn’t know this in the car. I knew that I hated the music, though, so there was no way I would endure watching one of these naïve pageants of neon blood, fully-clothed chaste cheek-kissing, and inexplicable eruptions of song and dance in scenes of romance or family dispute. I refused to see the fun in it, although my mother insists that I had a brief obsession with the last forty minutes of 1982’s Disco Dancer when I was a toddler. I do believe her, which means that technically I shouldn’t be allowed to write this Firsts essay, but any memory I had of Disco Dancer is on the mental equivalent of the BC landfill where the tape ended up. As I got older, I left the room when one of those dubbed tapes from the Indian grocery slid into the VCR, a departure of protest that was rightly ignored by the rest of the family. As far as memory serves, I have never watched a Bollywood film.

*

Eventually I came around to the music, at least, picking up on the obvious influence of Morricone on classic Bollywood composers like RD Burman, who in turn influenced the weird nerdy avant-garde metal I listened to in college. But the movies I still resisted, in the way I resisted reading Indian diasporic novels: I was annoyed at the idea that I was supposed to relate to them. The assumption that I was the ideal audience, not because of my attitude, but because of my background, was off-putting.

This expectation I felt not just from other abandoners, cast-offs, or born-aways from the subcontinent and all the little islands where the British had brought Indians to do their work, but from white classmates and professors and other writers who were a little surprised that I favour Amis over Rushdie, or that I wasn’t willing to give a pass to the wretched dialogue in The Namesake, due to the supposed importance of the story being told (as may be the case in my own life, the parents in that novel have the story you actually want to hear). The idea that I should necessarily care about these books more, and the gentle, sometimes unspoken, suggestion that the subject matter of my own writing was perhaps not quite brown enough: I have to admit, resistance in these matters may have changed the way I read, write, and watch. So even as I gained a deep appreciation for the Italian giallos and spaghetti Westerns that had a marking influence on '70s Bollywood, and as more of the music of Burman and his fellow Indian film composers crept into my playlists, I stayed away from the movies.

*

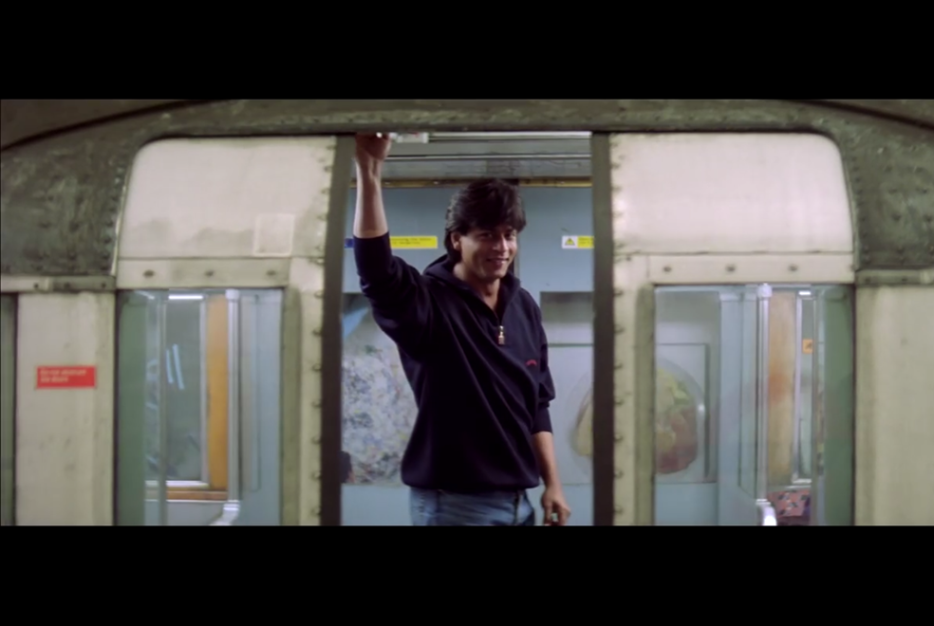

In the end, my girlfriend forced me to watch one. She gradually bullied me into sitting through her childhood favourite, 1995’s Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (a title taken from a nursery rhyme that translates, with leaden awkwardness, to The Big-Hearted Will Take Away the Bride). With the idea of writing about it not the furthest thing from my mind, I sat down to watch my first full Bollywood film, intermission and all. Watching it with someone who loved the movie and viewed it as frequently and obsessively as I rewatched Superman 2 when I was a kid seemed like the correct entrée into Bollywood.

In the spirit of a Firsts experience, I didn’t do a whack of auxiliary research. This strangled my ability to make knowing comments as the movie played, which is really part of my mode of being and one of many of the worst things about me. I knew it starred Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol, both of whom would become bankable Indian megastars on the back of the incredible success of Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. DDLJ (forever the film’s name to fans) is primarily interested in beauty, then in morality. Kajol and Shah Rukh are pale and sculpted avatars of that problematic ideal of Indian beauty on film, but the politics of their beauty don’t immediately leap out when you’re looking at them against the various European landscapes that they occupy in the movie.

Their faces, and the settings for that first half of the film’s three hours and nine minutes, are a holiday. What ended up onscreen in a Bombay cinema in 1995 and on my laptop in 2015 looks a lot like a video tourism catalog of places that are definitively not-India, highlighting the sights and landscapes of England and Switzerland. Lots of rolling hills and cobblestones.

The script has its stars doing everything from grand musical numbers to screwball banter to slapstick tumbling. Shah Rukh’s character, Raj, inevitably falls in love with the constantly exasperated and family-loyal Simran, but doesn’t want to try to convince her to run off with him. The twist this movie offers is one of combined acceptance: Raj understands that he has to be a real “Hindustani” and only carry off Simran with her father’s consent, and her father comes to accept (but only at the very last of those 189 minutes of runtime) that his daughter’s happiness is worth more than the traditional marriage that has been arranged for her.

About an hour in, as Raj turns a comic musical number into a display of authentic skills while bored Europeans watch and Simran pretends not to be impressed, I accepted that I was becoming the target audience. By the end, stirred by the authentic devotion between the starring characters, which the broad pageantry and chaste, goofy humour somehow enhanced, I even leaked a tear or two (which would be a bigger deal if I didn’t cry during about 70% of the films I watch).

Still, I’m not sure if I’ll be back. I think a taste for Bollywood is one that I would have had to develop a long time ago, shaping it in the crucible of childhood and adolescence, like the rest of my weird genre attachments. A background of fondness and nostalgia would help me endure the enormous runtimes of these movies, most of which land somewhere between Apocalypse Now and a season of Gilmore Girls in terms of hours of commitment required. Barely anyone in my immediate family watches Bollywood films anymore, except as Netflix background noise. I do think they’d be pleased or at least surprised to find out that I’d finally watched one, and may end up modifying their own changed habits to force a couple of these three-hour epics on me when I’m home next Christmas, which I why I won’t be sharing the link to this essay with them.