Even though I became a mother years before, I truly earned my flowers and breakfast in bed for Mother’s Day on a Tuesday eight years ago. I was two weeks overdue when I checked into the hospital to be induced. At the time, all I could think about was getting the baby out. I was huge. As my good friend put it, “you are the most pregnant woman I have ever seen.”

This was my second child and so the nurse decided to try a subtle method of induction. She used a cartridge full of gel to, as she put it, “ripen the cervix.” I already felt ripe, a fruit fermenting in my own skin. The other women in the room were mostly first-time mothers and had been sitting for long hours with IV drips inserted. Before long my waters burst with a loud pop. I assumed this swift outcome a result of my experience. “Excuse me ladies,” I muttered, as I waddled towards the delivery room. The second birth is easier, isn’t that what we say?

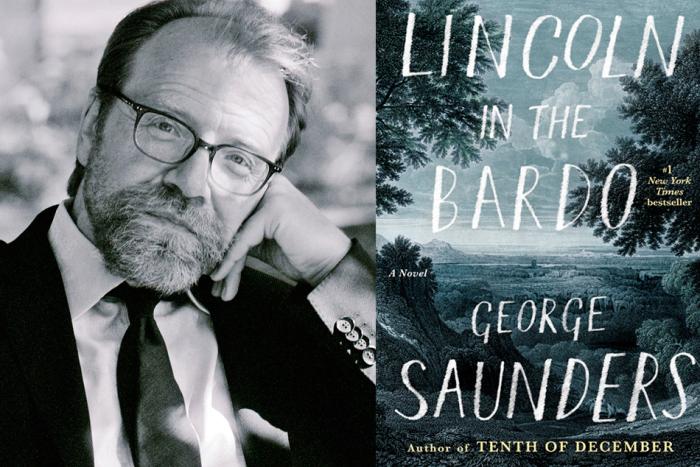

As I walked down the hall, my baby pulled down and dread set in. Including the placenta I had something roughly the weight of a bowling ball inside my body. It had to fit through a chamber that I prefer to think of as about the width of two of my husband’s fingers. My memories burst with an equally loud pop, the recollection of the first birth rushing back. Where were those memories when I needed them, the moment before I had unprotected sex? As Margaret Atwood writes in The Handmaid’s Tale, “who can remember pain, once it’s over?” The answer, I suddenly knew, was the woman who is about to give birth again.

A second labour tends to progress more quickly. My contractions soon came hard and fast. I intuitively knew that something was wrong, though I couldn’t say what. It felt like my muscles were attempting to rip me in two. My own body wouldn’t try to kill me, would it? In retrospect, I’m sure this was a kind of deeper instinct taking hold—an intuition that evolved thousands of years before anaesthetic, scalpels, or opioids came about. I wasn’t panicked; it was more like I settled into seeing everything more clearly. I was reminded of the handmaiden in Atwood’s novel, Offred. Her only choice was to give birth or die. Mine felt roughly similar. And as the pain increased, I became aware that I couldn’t stop the process. Any illusions of free will were gone. But unlike Offred, I didn’t live in a totalitarian state. My commands came from within.

Why don’t we talk more openly about what it is like to give birth? This is a question I thought about while writing my novel, The Last Neanderthal. UNICEF estimates that 353,000 babies are born around the world every day, that’s 4.3 babies every second, or over 120 million ever year. While medical care differs in each place, the process of vaginal birth is much the same. Our bodies have changed little in 40,000 years and birth is still as primal and raw as it was back then. Do millions of women all forget? While Atwood’s tale of dystopian birth is a notable exception, our stories of birth are often rosy—I picture a female actress on screen with a balloon tucked under her gown, moaning, spritzed with oil for sweat, but mascara in place. Splayed legs are considered a graphic touch and some light make-up stands in for blood, but these depictions aren’t only false for lack of haemorrhaging. The larger deception is that birth is only about life. In reality, the only certain thing about life is death and every birth contains that prospect.

*

My contractions grew stronger. I asked for an epidural, as I felt I needed my wits about me. Spinal fluid tapped, a drip inserted, I was positioned back on the birthing bed, the baby pressing heavily on my spine. I submitted once the drugs kicked in. A calm spread through me. That helped my body let go and soon I was ready to push. I collected myself by listening to the heart monitor that was strapped around my middle. I watched the needle chart his pulse. When it was time to push, I did. Immediately, the needle flattened. His rhythm slowed.

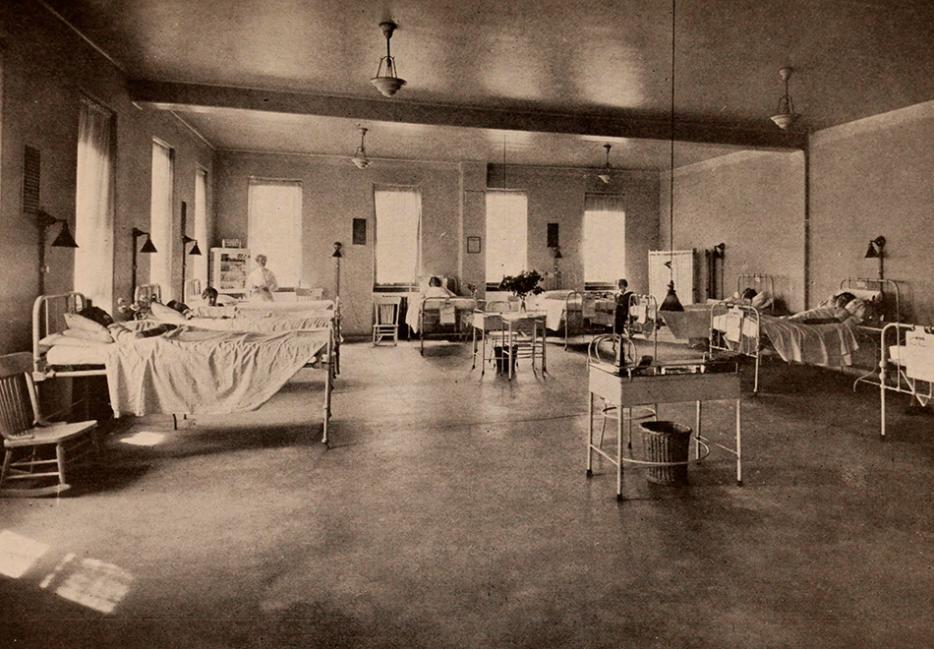

Death in childbirth used to be more ordinary. It’s said women in 15th-century Florence used to make out her will on learning she was pregnant, presumably an upper-class approach. Even now, estimates for the number of pregnancies that end in miscarriage are twenty percent or higher. While a mother is at risk, a baby is equally so. We all know many women who have had miscarriages, but how many come to mind? It’s probable that you can only name a few who are closest to you. “Pain marks you, but too deep to see,” says Atwood. Most women grieve in silence.

A nurse shouted something sharp. Chaos broke out in the room. Bodies wearing scrubs rushed in. A doctor screamed for a vacuum, eyes bulging, veins sprouting along the reddened skin of his neck. I watched this all with a kind of detached wonder, probably thanks in part to the epidural. But also, I wasn’t surprised. They had discovered what my body already knew.

The umbilical cord was wrapped twice around my baby’s neck. When I pushed the cord tightened. He was slowly strangling. I have been trained as a first responder and I knew the statistics for adults. After a minute without oxygen brain cells start to die. After three minutes, serious brain damage is likely. I assumed a new born had even less time.

The head doctor rushed to my side, ripped the heart monitor off my belly, the slowing beeps that amplified a small heart stopped. The doctor’s face now close to mine, “you have one push to get this baby out,” he held up a single finger in front of my face to show the stakes. “One.”

A new contraction rumbled up. I started to push. The vacuum was involved, hands pushed along my body, a nurse whispered instructions in my ear, but I knew I was beyond help from others. For all our advances and technology, this was up to me. I found the deep muscles near my diaphragm. I got to the end of what I thought was my strength, only to push twice as hard again. I felt the baby slip. Something took, like I got traction, and he started to move. I pushed harder. He came out with a sensation that felt like part of my life slipped away.

I looked at him, blue and slippery with a pointed head and lying on a silver tray. I didn’t need a doctor to tell me he was okay—somehow I already knew.

And now eight years later to mark these hours I get flowers, a card, and breakfast in bed. My son empties the dishwasher and plants a kiss on my cheek. And though I can remember the birth if I try, I also know why many prefer to live with our illusions about birth. It’s much easier to wish us “Happy Mother’s Day.”