In his writings on Charlie Chaplin, Roger Ebert often recounted a story of the 1972 Venice Film Festival, where the great comedian was being honoured. On the last night of the festival, after all of Chaplin’s major works had been screened, Piazza San Marco was cleared and City Lights (1931) was projected for a public audience. After the film’s iconic finale—in which the flower girl discovers that the benefactor who helped restore her sight was, in fact, a tramp—a spotlight shone at a balcony and a white-haired man waved at the crowd. “We stood still, silent, in awe,” wrote Ebert. “The hush lasted for three or four seconds, a very long time. And then we cheered and applauded and shouted ‘Charlie!’”

In his 1977 obituary for Chaplin, Ebert added a coda. The next day, meeting friends at a restaurant, he looked up to see the same white-haired man standing in the doorway, looking unhappy. “Look, there’s Charlie Chaplin,” Ebert shouted. The people at the restaurant applauded; the man smiled, waved, and left.

“What had I seen in his eyes, in the moment when no one else knew he was in the doorway?” Ebert wrote. “The child beaten in orphanages? The child who could never remember a time when he had not performed on the stage? The child who became the single most famous performer of the twentieth century, and who had just been cheered by ten thousand people as he stood on a balcony overlooking Piazza San Marco, and who now, less than a day later, was standing in the doorway of a hotel dining room… afraid he would not be recognized?”

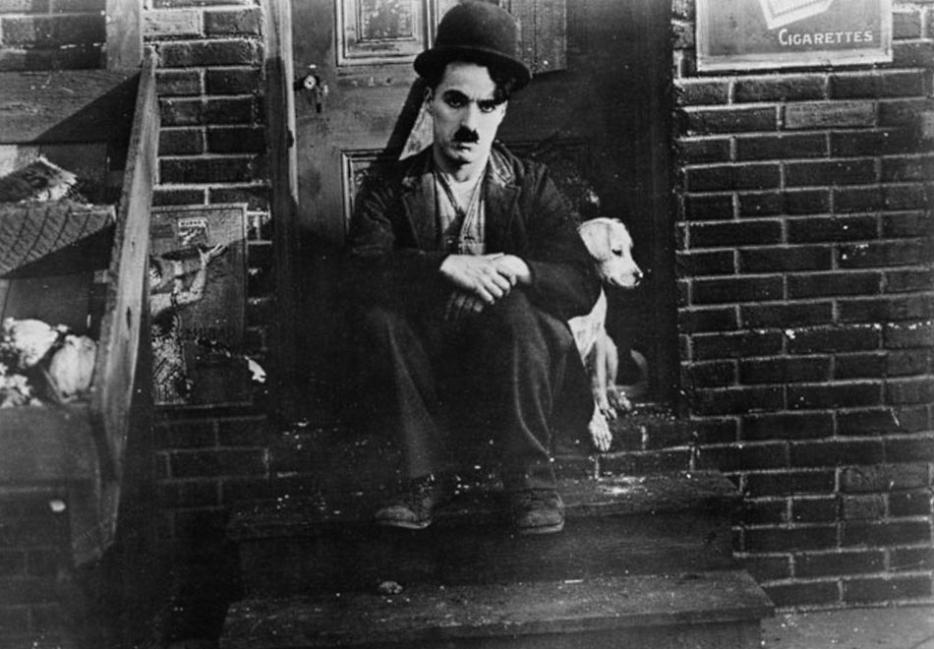

In 1913, Chaplin was a little-known English vaudevillian on tour in America when he was offered a chance to appear in movies. In 1914, when told to find a character for his second film, he quickly assembled what would become the most recognizable costume in film history: oversized pants, undersized jacket, derby hat, fake moustache, cane. The following year, at age 26, he’d become the first modern superstar—the subject of toys, comic strips, cartoons, and novelty songs. When he returned to London in 1921, he was mobbed at the train station; a similar reception greeted him in every country he visited.

By 1952, when he made his film Limelight, his politics and personal life had turned him into a pariah, the target of boycotts from groups like the American Legion and the Catholic War Veterans. Chaplin starred as Calvero, a comedian who has fallen on hard times—an ambiguous self-portrait that first appeared in Footlights, his unpublished novel.

In February, on the 100th anniversary of Chaplin’s debut film, the Cineteca di Bologna published Footlights for the first time. Its expanded story of Calvero gives an uncomfortable perspective on a beloved comedian at the lowest ebb of his career. For most of his life, Chaplin could depend on the love of his audience; Footlights shows what it’s like when the audience is gone.

*

Early in Footlights, Calvero, the faded comedian, visits the Queen’s Head Bar, a popular spot for London’s theatrical community. The year is 1914, and it has been three years since Calvero has headlined a theatre; he has come to the bar to meet with his agent, who stands him up. “In the old days, his entrance would have been the cue for general excitement and a welcome from the proprietor,” writes Chaplin. “But now it called for little or no attention, and if he were recognized, it meant but a perfunctory nod or a cold glance of curiosity.”

Calvero, we learn, was once the biggest comedian in London: His small apartment is “a museum of theatrical antiquity,” decorated with old playbills, posters, and publicity photos. But even at his peak, Calvero was uneasy with his audience. He thought that alcohol made him funnier; over time it made him undependable, and his bookings dried up. At night, the old Calvero dreams of performing his wheezy flea circus bit to an empty audience, singing:

I’ve trained animals by the score:

Lions, tigers, and wild boar.

I’ve made and lost a fortune,

In my wild career.

Some say the cause was women:

Some say it was beer, some say it was beer.

Calvero finally gets a booking at a dodgy venue, where he hopes to reestablish his career. Instead, the audience heckles him and files out during his act. In Limelight, we follow Calvero to his dressing room, where he picks off his moustache and wipes away his makeup. When he runs his hand across his head, the salt-and-pepper hair turns white, and the camera lingers on his sad expression.

For most of his life, Chaplin could depend on the love of his audience; Footlights shows what it’s like when the audience is gone.

One afternoon, Calvero staggers into his building and smells gas in the hallway. He breaks down a door on the main floor and finds a young woman named Thereza Ambrose trying to commit suicide. Thereza (“Terry” for short) was an aspiring ballet dancer who lost the use of her legs from malnourishment, exhaustion, and pneumonia—but we eventually learn that her paralysis is largely psychological.

Calvero’s decline finds a counterpoint in Terry’s rise. After he nurses her back to health, she regains control of her legs, auditions with the prestigious Empire Ballet, and begins a meteoric ascent to stardom. She also falls in love with Calvero, and has him dreaming of a comeback. She tells him he loves people too much to stay bitter at his audience. “There’s greatness in everyone,” Calvero replies, “but the audience—they are what they are—a motley confusion of cross purposes.” He continues:

“I know I’m funny, but the managers think I’m through... a has-been. God! It would be wonderful to make them eat their words. That’s what I hate about getting old—the contempt and indifference they show you. They think I’m useless... That’s why it would be wonderful to make a comeback! ... As much as I hate those lousy—I love to hear them laugh!”

*

Chaplin was 25 when he made his first films; he wore the fake moustache to look older. He became very rich very fast, diverging early from the innocent, humble Little Tramp he played onscreen. Chaplin’s onscreen image was so different from his off-screen one that it may have insulated him from scandal: no other star would have survived a pair of shotgun marriages to teenagers (Mildred Harris and Lita Grey, both 16). Grey’s divorce case, with its salacious detailing of Chaplin’s sexual tastes and extramarital affairs, became an underground bestseller in bootleg form, but not even this seriously affected his popularity.

But Chaplin couldn’t outrun scandal forever. In 1941, he began work on a film adaptation of Paul Vincent Carroll’s play Shadow and Substance as a vehicle for his new discovery, Joan Barry. Chaplin was taken with the 21-year-old actress, and after signing her to a contract, began an affair. Over time, Barry became erratic, drinking heavily, appearing at his home at strange hours, and on one hair-raising evening, holding him at gunpoint. Chaplin dropped both the film and Barry, but when she became pregnant, she took him to court. In 1943, Barry sued Chaplin for child support; the U.S. government, in collaboration with Barry, charged him with violating the Mann Act (a law against transporting women across state lines for sexual purposes, intended to stop human trafficking and applied quite liberally here).

Chaplin was acquitted of the Mann Act charge, but blood tests proving he was not the father of Barry’s child were inadmissible—Chaplin would have to pay child support. Moreover, 30 years of personal indiscretions finally caught up with Chaplin when Joseph Scott, Barry’s attorney, addressed the jury. According to Scott, the 54-year-old star was “a little runt of a Svengali,” a “lecherous hound,” and a “cheap, Cockney cad.” The same year as the trial, Chaplin married his fourth wife, Oona O’Neill, the 18-year-old estranged daughter of Eugene. The union would last until his death and produce eight children, but given the age disparity, it was seen at the time as further evidence of his immorality.

The Joan Barry affair came during a time when his politics were already making him deeply unfashionable. His anti-Nazi satire The Great Dictator (1940) had been a hit, but raised red flags for many anti-interventionists. At the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover was monitoring his friendships with left-wing intellectuals (especially the composer Hanns Eisler, a target of the House Committee on Un-American Activities); Hoover called him a “parlor Bolsheveki,” and his FBI file eventually ran over 2,000 pages. His interest in left-wing causes caught the ire of conservative columnists like Hedda Hopper and Ed Sullivan, who pointed to Chaplin’s advocacy for a Russian front in the war as evidence of communist sympathies. They also lambasted him for never applying for U.S. citizenship. Chaplin’s explanation—“I consider myself a citizen of the world”—didn’t win him many friends.

Twenty years earlier, he might have won back the public with a movie, but deep into middle age, Chaplin felt he was too old to play the Tramp. In Monsieur Verdoux (1947), he played a bank teller who loses his job in the Depression, and supports his family by marrying and murdering rich widows. Verdoux, who has been failed by the system, applies a dehumanizing capitalist logic to his line of work, dismissing the murders as “simply business.” The movie was the culmination of Chaplin’s growing interest in politics, and critics wouldn’t separate him from the icy, cynical Verdoux. The film was marketed with the tagline, “Chaplin Changes! Can You?,” and the challenge proved too great.

At the premiere, Verdoux met with tepid laughter and a few hisses, like those that greeted Calvero. At the New York press conference, journalists asked loaded questions about his politics and private life. Chaplin was devastated by the failure—throughout the Joan Barry ordeal, he never doubted he could deliver a hit. In interviews, he claimed that Calvero was based on vaudevillians he had known in his youth who had lost the audience’s love, but when he wrote Footlights in 1948, surely he was thinking of himself.

Limelight, the resulting film adaptation, was completed in 1952, long after Chaplin’s Hollywood mansion had ceased to be a hotspot for visiting luminaries. En route to England for the film’s London premiere, Chaplin learned that the Attorney General’s office had revoked his American re-entry visa, citing him as a security risk. He was told he would need to re-apply for admission and undergo a “loyalty test.” While he may well have passed, he took the hint, resettling his family in Vevey, Switzerland.

*

Calvero’s story invites an autobiographical reading; in Limelight, Chaplin throws in some direct references to his life, as if acknowledging this. Calvero, in his heyday, performed as a “Tramp Comedian,” and when he is reduced to working as a busker, he says, “There’s something about working the streets I like. It’s the tramp in me, I suppose.” A well-known portrait of Chaplin circa 1915 decorates his apartment. Later, the arrival of Buster Keaton as Chaplin’s sidekick gains resonance from our memories of the two as rivals in the silent era. “If anybody else says ‘It’s like old times,’ I’ll jump out the window,” says Keaton, as he and Calvero get dressed before the big show.

But one senses that Calvero is more a reflection of Chaplin’s state of mind than the particulars of his career. There are indications in Footlights that Calvero grew unreliable and difficult, but Chaplin was his own financier and (with United Artists) distributor, answering to no one but himself. Both came out on the wrong side of a string of divorces, but Chaplin otherwise kept a tight grip on his money, and ended his life a wealthy man. Chaplin also abhorred alcohol; for Calvero’s alcoholism, he might have drawn on his father, a music hall comedian who drank himself to death.

Over time, Barry became erratic, drinking heavily, appearing at his home at strange hours, and on one hair-raising evening, holding him at gunpoint.

Chaplin was born in London in 1889, the son of vaudevillians of Calvero’s generation. In My Autobiography, Chaplin’s 1964 memoir, his father, Charles Chaplin Sr., is a ghostly presence—estranged from the family since before his son was conscious, and dead by age 37. “It was difficult for vaudevillians not to drink in those days … after a performer’s act he was expected to go to the theatre bar and drink with the customers,” Chaplin wrote. His drinking made him undependable, and his bookings evaporated. His main contribution to his son’s life was introducing him to a theatre manager, who put young Charlie in the Eight Lancashire Lads at age nine. Charlie began touring with the troupe, and thus began his show business career.

Chaplin biographers have traced Terry, Calvero’s romantic interest, to Hetty Kelly, a 15-year-old showgirl who had once rebuffed Chaplin’s marriage proposal. He hoped to reconnect with her in 1921, during his first visit home post-fame, but was shocked to discover she had died in the flu pandemic of 1918. Terry may also have been inspired by Hannah Chaplin, his mother—a minor singing star until her voice was weakened from laryngitis and overwork. In the middle of her act one night, she lost her voice altogether, and five-year-old Charlie stepped up in her place, sating the crowd with a song. In his autobiography, Chaplin recalled this as his stage debut. “I was quite at home. I talked to the audience, danced, and did several imitations including one of Mother singing her Irish march song.”

Hannah Chaplin would never appear onstage again; she tried to support the family as a dressmaker, but they fell into poverty nonetheless. Chaplin wrote of how she kept the boys’ spirits up in deprivation:

“If it had not been for my mother, I doubt I could have made a success of pantomime. She was one of the greatest pantomime artists I have ever seen. She would sit for hours at a window, looking down at the people on the street and illustrating with her hands, eyes, and facial expression just what was going on below.”

In the years that followed, Hannah drifted in and out of sanity. Chaplin’s autobiography attributes her fate to malnutrition; in the Cineteca publication, biographer David Robinson cites research suggesting she suffered tertiary syphilis. “Vaguely I felt that she had deliberately escaped from her mind and had deserted us,” Chaplin wrote. Charlie and his older half-brother, Sydney, spent time in a workhouse, and were moved to an institution for orphaned children. They supported the family with various odd jobs and vaudeville gigs. At age 14, when he found his mother wandering the streets and knocking on doors, Charlie had her committed to an asylum.

Footlights reveals Terry’s backstory in greater detail than Limelight, and hints at another source for the character. We learn that her father died when she was seven, leaving her alone with her sister and mother, who “had rare beauty, but that was now spent, through years of poverty and care,” and struggled to support the girls as a dressmaker. When their mother falls ill from overwork, Terry’s sister Louise has to support the family as a streetwalker. Chaplin writes of Terry’s shock in excruciating detail.

Terry lives much of her childhood in poverty, and spends so many afternoons in the parks of London that they become symbolic of sadness, just as they did for Chaplin, who refused to visit them in adulthood. Growing up, she develops a talent for dance, and her success in the theatre elevates her from destitution to stardom. When success comes, it is greater and more sudden than she could have dreamed. With her newfound clout, she helps Calvero by giving him work in the ballet; when Chaplin found fame, he was able to bring his mother to California, despite policy against immigrants with mental illness.

In Limelight, Terry’s character invited speculation into Chaplin’s family, and her relationship with Calvero suggested the women in his romantic life. What Footlights reveals is how much of Thereza Ambrose is Charlie Chaplin himself.

*

Chaplin was no longer Thereza by the time he made Limelight. Even with his popularity at a nadir, he wasn’t really Calvero either. He still had money and independence, and could still make a film whenever he wanted. Even if he was unpopular in America, he could still sell Limelight around the world, and break bread with kings and presidents in Europe and beyond.

One who wasn’t so lucky was Buster Keaton, who lost creative control over his films and saw his career flame out in alcoholism. In the ’40s, Keaton was reduced to writing gags for Abbott and Costello; in Sunset Boulevard, Billy Wilder cruelly cast him as one of the “Hollywood waxworks” at Norma Desmond’s poker table. According to assistant Jerry Epstein in his 1989 book, Remembering Charlie, Chaplin was looking for a veteran comedian to accompany Calvero in his triumphant final performance when he heard that Keaton was destitute. By Epstein’s account, Keaton got the part out of charity.

Maybe Chaplin was using him as Wilder did; perhaps he saw Keaton as the real-life Calvero he feared becoming. Or maybe he was genuinely troubled by Keaton’s plight. But whatever Chaplin had heard, Keaton was actually on the upswing thanks to regular TV appearances and a successful marriage. “Apparently he had expected to see a physical and mental wreck,” Keaton noted wryly in his autobiography. Chaplin and Keaton spent two weeks improvising their routine, which is, not coincidentally, the only funny scene in the movie. By Epstein’s account, the two had a cordial but exclusively professional relationship, and Epstein expresses some peculiar sourness about the buzz Keaton’s presence inspired on set.

During the silent era, Chaplin and Keaton were friendly, if not close. Keaton sometimes claimed that they traded gags, but in critical esteem and popular success, Chaplin was the undisputed leader. By the 1960s, however, Keaton’s dry, modernist films were very much in vogue with intellectuals, who often preferred them to Chaplin’s more sentimental, Victorian work. Keaton partisans circulated the rumour that a jealous Chaplin had cut Keaton’s best moments from Limelight, and while this report has been widely debunked (including by Keaton), the legend still circulates.

Despite his key role in Limelight, Keaton doesn’t even merit a mention in Chaplin’s 1964 memoir—nor does Stan Laurel (who he performed and roomed with in vaudeville) or Harold Lloyd (his chief box office rival) or the Marx Brothers (vaudeville contemporaries) or any other comedian besides a few immediate collaborators. Such omissions might be understandable if the rest of the book weren’t so busy chronicling Chaplin’s high society friendships (“If we were not so preoccupied with our family, we could have quite a social life in Switzerland, for we live relatively near the Queen of Spain and the Count and the Countess Chevreau d’Antraigues”).

Is it possible that Chaplin resented Keaton’s rise in popularity, and feared other comedians might eclipse him? This would seem irrational and petty—by 1972, Chaplin’s reputation was rehabilitated to the point that he could return to America for an Honorary Oscar and receive the longest ovation in Academy history. But in the 2003 documentary Charlie: The Life and Art of Charlie Chaplin, Chaplin’s daughter Geraldine recalls bringing home a boyfriend who fervently admired Keaton. As he raved about Keaton’s work, Chaplin grew withdrawn, and remained quiet until late in the evening. Finally, he spoke up. “But I was an artist… and I gave him work.” Perhaps the fear that created Calvero never left him.