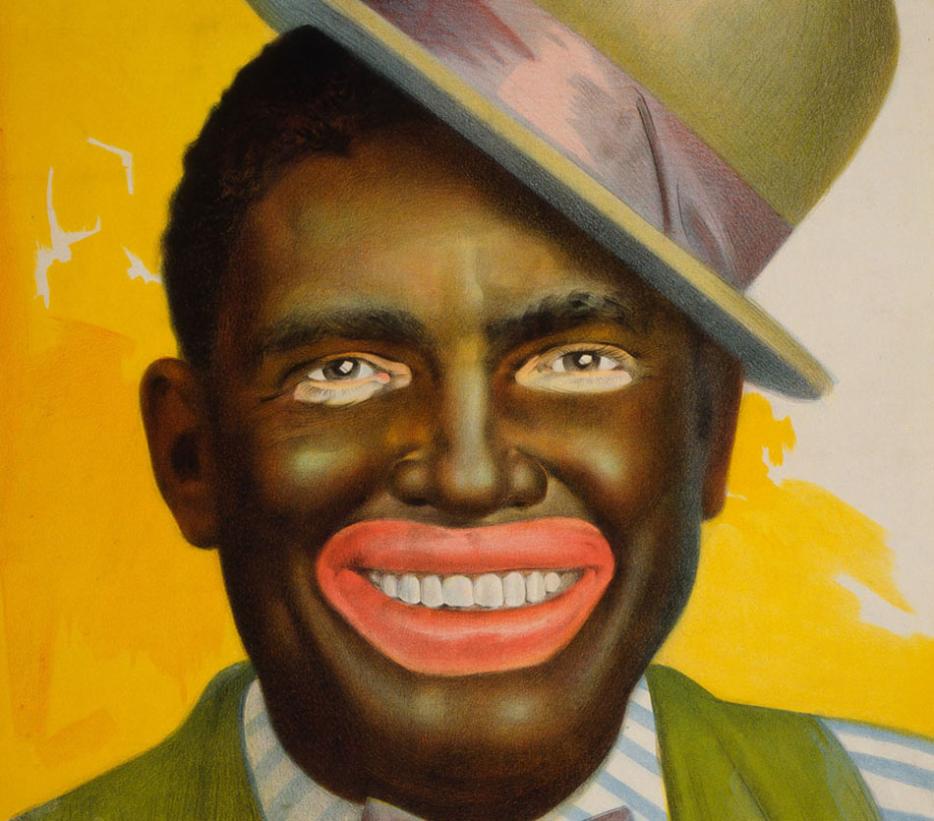

Nick Tosches’ 2001 book, Where Dead Voices Gather, about the enigmatic blues singer Emmett Miller, is so full of facts it can barely do up its pants. By the time the book came out, Tosches had been shaking the archives for over 25 years trying to figure out his subject, only to watch him disappear on the page: the more facts he uncovered, the more Emmett Miller seemed to recede into a fog of contradiction. Miller was, and is, a ghost. But if Tosches is right, this ghost is a phantom link in the story of Western pop music, a direct descendant of both modern country and hip-hop, the spiritual great-grandfather of Taylor Swift and Kanye West, but with a fat troubling fact at the heart of his story: Emmett Miller was a minstrel singer in the 1920s, a white man who performed in blackface.

Miller sang in a strange, strangled yodel, described by Tosches as “a bizarre malarkey of the soul that seemed a death-cry and a birth-cry too: the last mutant mongrel emanation of old and dead and dying styles...” In fact Miller was the last minstrel, before pop music owned up to its anxieties about lampooning black culture and settled, instead, for quietly stealing from it. For Tosches, Miller is the last connection to pop’s own darkest roots. But what’s most interesting about the book is how Miller seems complicit in his own disappearance from the historical record, as if even in death he’s ready to say: forgive me if you want, but for God’s sake forget me. For its part pop culture is happy to prune its thorny past. But Tosches can’t help himself: he heard the voice, the death-cry and birth-cry, and was haunted.

Here’s what we know: Emmett Miller was born in 1900 in Macon Georgia and died there in 1962, buried under a flat marker in Fort Hill Cemetery. For a time he toured with a band called the Georgia Crackers—which featured future stars Gene Krupa and the Dorsey brothers, Jimmy and Tommy—and in 1924 made his first record, “Anytime,” for the Okeh label in New York. Tosches sniffs a smoking gun in Miller’s recording of a standard called “Lovesick Blues” the following year: this is the song that Hank Williams covered in 1949 and which launched his crossover career and everything that followed, if you’re inclined to follow the org chart that leads from Hank Williams to Jerry Lee Lewis to rock ‘n’ roll to Coldplay. Follow the yodel: both Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers get credit for pressing country blues into the mainstream, and both built their signature sounds on that tricky falsetto gimmick for which Emmett Miller was famous, on the vaudeville circuit and the Okeh recordings.

Had they heard him? There’s no proof they ever did. Besides, the yodel has its own rural tradition and can even be linked (although Tosches doesn’t go there) to operatic coloratura: games voices play to amuse and baffle the ear. But the point, for Tosches, is that pop has many parents, legitimate and otherwise, and it’s folly to think of Williams and Rodgers as some kind of cultural Ground Zero: “What we claim as originality and discovery,” he writes, “are nothing but the airs and delusions of our innocence, ignorance and arrogance... whatever is said was said better—more powerfully, beautifully, and purely—long ago.” In the case of Hank Williams’ “Lovesick Blues,” which changed the world, there’s at least a chance that the bloodline leads directly back to Emmett Miller.

Tosches went looking for surviving bandmates and relatives and came up with a few who barely remembered the man or confused him in their memories with other Emmetts in the entertainment racket, including the circus clown Emmett Kelly. His nephew-in-law remembered Miller as “a rounder... If that man hadn’t drank so much, he would’ve been a millionaire.” He told Tosches of the time Miller and Hank Williams got drunk together and wrote “Lovesick Blues,” which the old minstrel singer gave over to Williams. Tosches didn’t have the heart to explain that “Lovesick Blues” was written before either was born, but such was the self-fuelling machinery of family folklore. “You might say he was a nice guy,” said the nephew when pressed for details of what made Emmett Miller tick. “When he was sober, he was a nice guy.” He also remembered that Miller liked to keep his shoes shined and his trousers pressed. Those impressions, plus a couple of publicity photos, the Okeh recordings, and a flat grave marker, were all that remained of Emmett Miller by the time Nick Tosches caught up to him.

The book, as I said, is hectic with detail, not so much on Emmett Miller’s cryptic life as its context: the history of white minstrelsy, the frantic musical crossroads of the 1920s when jazz and blues and Tin Pan Alley and the movies were all poised to drive, and be driven by, mainstream commerce. Miller’s America, according to Michael Rogin of UC Berkeley (cited in Where Dead Voices Gather), was a “capitalist society permeated by a longing for a lost, pre-industrial feudal home,” or in other words, an America nostalgic for slavery. People liked the blackface because it gave them, as entertainment, an African-American character they missed: the one happy and carefree and in chains.

For Tosches the idea is astute but “fatuous nonsense”: blackface minstrelsy was born not in the South but in the more liberal North, in New York, and black entertainers wore the makeup too. Sociology, he says, had little to do with it: it was comedy based on exaggerated ethnic stereotyping (which, he points out, has never gone away), and for the performers it was just a way to make money. Of course Tosches’ argument is a dodge. “Let our excavations in the graveyard of data,” he writes, “our journey through the haunted carnival of endless night, be undefiled by thought itself, which, in Miller studies as in life, is the enemy of truth as if the soul.” Which is a purple-pretty way of saying, don’t think so much: we are chasing a ghost and the weight of ideology will only crush the spell.

The problem, and Tosches never fully gets at it, is that America’s whitewashing (forgive the pun) of its own history is perhaps the reason why Emmett Miller disappeared from the record: better to hide him than tie him to its heroes. And we have to wonder how much of his exile was self-imposed. In a peculiar and chilling passage, Tosches admits that, while compiling the research for his book his own computer files on Miller had been “spontaneously obliterated,” turned to gibberish, not once but twice, as if the ghost had insinuated itself into the machine to erase its own story. “I think Emmett Miller is evil,” one of the author’s friends tells him.

But Tosches can’t shake him. Hidden in the text of Where Dead Voices Gather with all its digression and dodging is the idea of artistic obsession: we don’t get to pick passions, they find us, and logic and ideology and sociology, for all their value, mean little when the music or story traps us somewhere between common sense and a dream. In a way the Tosches book is like a dream, or a nightmare, in which the central figure emerges half-formed, maybe pop music’s uncredited genius, or maybe a monster. The point is not what the dream means but the vivid noise it makes: the “bizarre malarkey of the soul,” that’s all that matters, at least to the dreamer. It’s a cop out, but we all know the feeling.