A wife refuses her husband’s request to remove the green ribbon tied eternally around her neck. A store clerk realizes there are girls sewn into the dresses she sells. A woman recalls her sexual encounters as a plague consumes the world.

The world of Carmen Maria Machado is bright and bizarre, full of magic and haunted places. Much of Machado’s short fiction centers on the unexpected, the swerve into the night vision of a woman who is really a witch and just remembered to tell you.

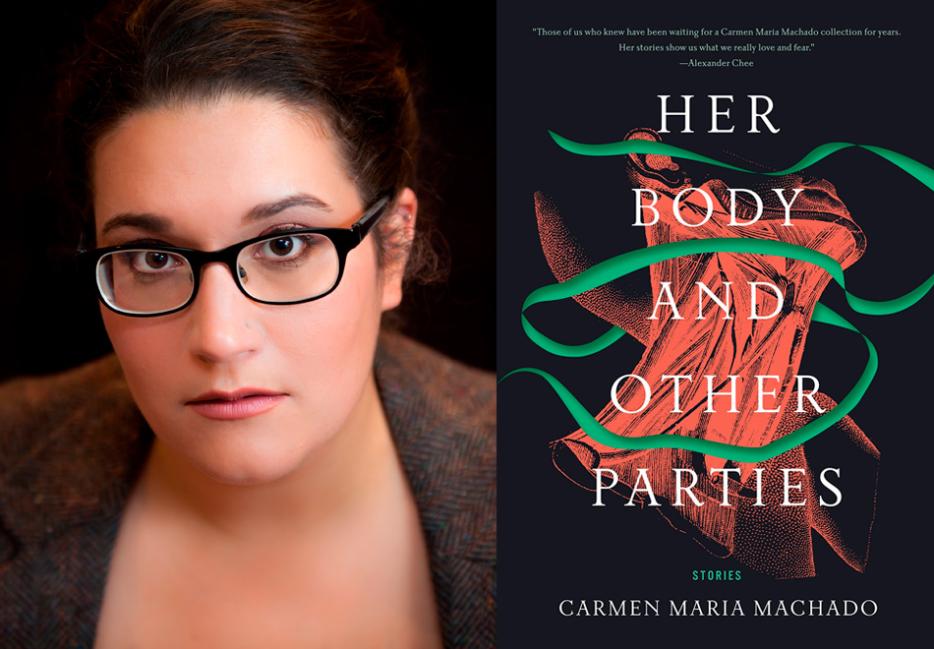

In Machado’s debut short story collection Her Body and Other Parties (Graywolf Press), recently nominated for a National Book Award and the Kirkus Prize, she weaves the real with the fantastic until the ordinary becomes sinister and the other way around.

Lyra Kuhn: When did you first become interested in fabulism?

Carmen Maria Machado: I think my interest in fabulism has come to me in stages. As a child, I was drawn to fabulist writing through kid’s lit—fantasy (A Wrinkle in Time) and science fiction (Ray Bradbury) and horror (Lois Duncan, John Bellairs), cut with metafiction (Sideways Stories from Wayside School) and absurdism (Roald Dahl).

As a teenager, I was lucky enough to have a particular teacher who gave me books to read from her personal library, like One Hundred Years of Solitude, which was my first exposure to magical realism.

And I had a third, important stage right after I began grad school, and fellow students began recommending writers to me who have since become the backbone of my personal canon: Kelly Link, Karen Russell, George Saunders, Nicholson Baker, Helen Oyeyemi, Alice Sola Kim, Sofia Samatar, Shirley Jackson, Angela Carter. This final stage was the push I needed for my own work; I realized these were the types of stories that spoke the most intensely to me, and reflected something I wanted to do in my own fiction.

How does your identity as queer and Latina affect your writing?

I think writing is inextricable from the body; there’s no such thing as pure reason, pure intellect. My body, my identity, is a lens through which I can view the world and reflect it back in my work. This is true for every artist.

Do you think the body is a source of horror? Do you think bodies can become haunted?

I do! Bodies are terrifying; they’re powerful and fragile, bloody and imperfect, uncanny, impressionable vehicles that carry our minds from birth until death. And of course they’re inherently haunted. Haunting is a kind of impression; a lingering effect from a physical act like a shoeprint or a cloud of perfume left in the air. In the same way, bodies carry trauma and choices of our ancestors. Our DNAs are blueprints of the past.

Is there a particular approach you take when writing a fabulist story, an alchemical process of sorts?

Not really. Most stories come together in the same way for me—in pieces, images, impressions, and concepts that I have to gather together into something cohesive. Whether or not the story is fabulist is pretty incidental to the process.

There is an image in the book that hasn’t left me for some time—when the narrator from the story “Real Women Have Bodies” first describes the disease that makes women disappear, then later realizes the terrible secret about the dresses in the shop. Where did the crux of this story come from?

At the Coralville Mall, right next to Iowa City, there was a black-walled, seasonal-prom-dress store called Glam. I walked past it one day, and thought Wow, that’d be a great setting for a story. I’d been mainlining a lot of fabulism around that time—I think I’d just finished Karen Russell’s St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves—and so I tried to imagine what kind of horrors could happen there. I don’t know how I arrived at the faded women being stitched into the dresses, but I imagine it had to do with the fact that the dresses already looked like they were occupied by invisible bodies. The story unfurled from there, though it’s old enough that it was heavily rewritten on a sentence level before appearing in Her Body and Other Parties.

How do you move between the real and the unreal in your stories?

I don’t think of them as particularly separate; the scrim between them is barely there. So it’s not difficult: I look at the world around me and push into it, just a little.

Why do you think so many women writers turn to the uncanny, such as yourself, Kelly Link, Karen Russell, and so on?

I think there are probably lots of reasons, but one of them is that being a woman is inherently uncanny. Your humanity is liminal; your body is forfeit; your mind is doubted as a matter of course. You exist in the periphery, and I think many women writers can’t help but respond to that state.

You’ve said before that you have an obsession with lists. Could you make a list of stories or books that have had a great impact on you?

Sure! Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day, Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and The Lottery and Other Stories, Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, Kelly Link’s Stranger Things Happen and Magic for Beginners, Alissa Nutting’s Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls, Karen Russell’s St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, Nicholson Baker’s Mezzanine and Vox.