It would have been a surprise to Mohamed Bouazizi to learn that he martyred himself for sexual liberation. When Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor who was Time’s 2011 Person of the Year and whose face is now on a postage stamp, set fire to himself on the street in Sidi Bouzid, he thought he was protesting the fact that police had unfairly confiscated all his fruits and vegetables yet again. But his self-immolation is considered the catalyst of the Arab Spring, in which millions across the Middle East demanded—and got—political change. Few predicted that the populations of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen were ready for political revolution—could it be that the changes in the Arab world are sweeping it along towards an even more daring sexual revolution?

In her book Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World, Shereen El Feki argues that conditions in the Arab world closely resemble those that strained the sexual mores of 1950s America: urbanization, with attendant weakening of family control; a young population; and a growing sense of personal identity outside the collective. When America’s buttons popped, there was bare skin underneath.

El Feki sees a new dialogue emerging in the Arabic home and media. When Amina Tyler, a 19-year-old Tunisian, posted naked photos of herself on her Facebook page last month, with the words “my body is my own and not the source of anyone’s honour” written in Arabic script on her chest, clerics called for her to be stoned to death. Even the leaders of the Arab Spring’s youth movement wrote letters condemning her and making clear that this was not the revolution they were after. But even expressing the sentiment in a public forum is something new.

Islamic sex therapist Heba Kotb, who launched Egypt’s immensely popular sex-advice TV show Big Talk in 2006, is also seeing changes in her practice. When she first set up an office where married couples (and married couples only) could come to discuss their sexual difficulties, her clients were mostly coming at the man’s initiative; post-Arab Spring, she says, it’s the reverse. “Women are more courageous now to accuse their husbands of not being good [in bed]. It is the spirit of the revolution,” she told El Feki. She mentions a husband who was only having sex with his wife once a month. The wife demanded better, saying “I don’t accept this relation. We are like brother and sister living together here, and you have to do something about yourself.”

Unlike, say, Christianity, Islam actually has a strong history of sex-positive messaging. In the 11th century, the Catholic church was enshrining celibacy as the highest religious expression. Meanwhile in Baghdad, ‘Ali ibn Nasr al-Katib was writing his Encyclopedia of Pleasures, with chapters like, “On Increasing the Sexual Pleasure of Man and Woman,” and “Description of the Nasty Way of Doing It and Lewd Sex.” Much of the book focusses on how to fulfill women’s insatiable sexual desire, through cunnilingus, French kissing, and post-orgasm cuddling.

In fact, El Feki argues that the clamping-down on sexual freedom after the colonial era was a reaction to the way Westerners saw Arabic culture—uptight Victorian Englishmen had been scandalized by the tolerance for homosexuality and the clerics with multiple wives. The prophet Mohammed reportedly decreed that he who performs insufficient foreplay and doesn’t bother to satisfy his wife’s sexual needs was failing to live a virtuous life. “Let none of you come upon his wife like an animal, and let there be an emissary between them,” the Prophet said. “What is this emissary, O Messenger of God?” a follower asked. “The kiss and [sweet] words,” the founder of Islam said.

The idea that sexual revolution and political revolution are linked—indeed, the term “sexual revolution”—goes back to an Austrian psychoanalyst and disciple of Freud’s named Wilhelm Reich. His fiery 1936 book, The Sexual Revolution (reissued most recently in 1992) argued that, “Since the core of emotional functioning is the sexual function, the core of political (pragmatic) psychology is sex politics,” and, “[t]he small, wretched, allegedly ‘unpolitical’ sexual life of man must be investigated thoroughly and mastered in relation to the problems of authoritarian society.” Reich saw the traditional family structure as a tool of fascist suppression, in which sons and daughters brought up to obey the authority of their father marched unquestioningly to the martial drum of the capitalist state.

Reich was hoping for a socialist solution to both the sexual and political problems of his day, which is not where the Middle East seems to be headed. But his ideas are relevant to the development of any kind of democratic system. Democracy serves a collective, national self, but votes are cast by individuals; part of the democratic process is freedom of individual dissent. According to El Feki, the success of the Arab region’s political progress is therefore dependent upon a rethinking of sexual values. “You can change the political system, but that doesn’t mean the sexual order changes with it,” she admits. “But if you don’t change the sexual order of things, freedom will never stick.”

It’s curious that El Feki sees evidence of a shift towards sexual freedom in Egypt and nearby regions—most news stories will tell you the opposite. In an article about the lead-up to the 2012 elections, the Guardian wrote: “If you were to read a first draft of last year's Egyptian revolution, it would probably be written by a woman....How dispiriting, then, a year and a half on, to see a highly politicised female population relegated to near-onlookers during Egypt's first bona fide presidential election race.” Suzanne Mubarak, former first lady, had been an active proponent of women’s rights in Egypt, and prominent human rights activists like Dalia Ziada have recently been quoted saying that conditions for women were better under the Mubarak regime. The old regime’s quota for women in government—a guaranteed 64 seats out of 534—may not sound like much, but the new military government quickly scrapped it, and the Egyptian parliament now has only nine women MPs out of 508. Laws governing women’s right to divorce may be repealed, and some Muslim Brotherhood clerics believe it should be permissible to marry nine-year-old girls. Assault, rape, and harassment are on the rise.

But what struck me most about El Feki’s travels in the Arab world was not so much the absence of sexual fulfillment; it was the difficulty of finding romantic fulfillment in marriage. The Cairo women that El Feki meets with regularly “complain that, honeymoon over, their spouses rarely show them much physical or emotional affection, and there is precious little companionship on offer.” Ana bahibbik—“I love you”—is a popular lyric for songs on the radio, they say, but not on their husbands’ lips. “I swear,” says one woman, “no one of my friends, her husband says ‘I love you.’ Only the first year of marriage. They feel that this is shame, to say ‘I love you.’ Men feel they are very weak when they say ‘I love you.’”

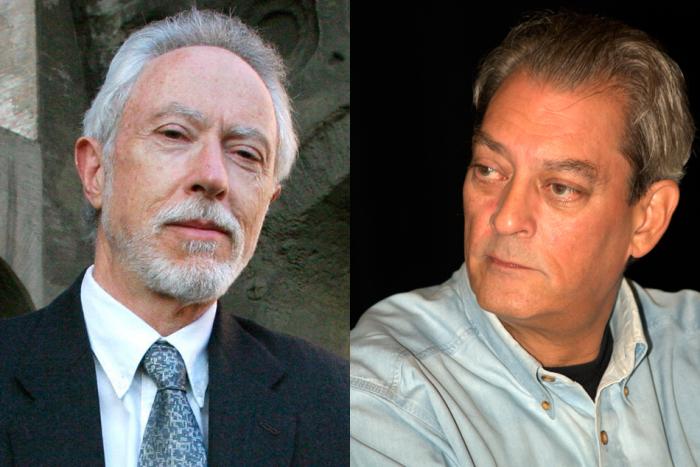

Wilhelm Reich, in true revolutionary style, died in jail. In his case, however, it was at the behest of the Food and Drug Administration. Reich’s daffy vision of a sexually satisfied and politically transformed electorate led him to invent a sexual enhancement chamber—a phone booth-size box—that he claimed would funnel in all the erotic energies of the air and turn the user into a sexual Superman. Although Jack Kerouac claimed to have reached orgasm in his with “no hands” (Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow, and J.D. Salinger all bought or built Reich’s sex boxes too), the FDA ruled that the box’s powers were bogus, and ordered Reich to stop selling it. He refused, and died unrepentant in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in 1957—just a smidge too early to see “free love” emerge as a political statement in the 1960s.

Whether today’s Arab Spring will turn into an Arab Summer of Love remains to be seen. But democracy is about coming together for collective self-determination, and listening to each other as we struggle to state our needs. Perhaps the place to start isn’t sex at all; maybe it’s love.