1. Get to the train station early and nab myself a window seat. A teenage boy asks if the seat next to me is taken. He’s at the age where boys speak in monotone because they think modulating your voice is for sissies. He farts throughout the entire trip and tries to hide it by arching his back as if he’s just stretching. That’s the great thing about VIA Rail economy class: it gets you out of your liberal urban enclave and expands your horizons.

2. Symposium, “A Radical Re-Imagination of Music in Canada: Engaged Audiences and Creative Possibilities”—which, featuring three Montreal music folks (musicians Tim Hecker and Caila Thompson-Hannant, aka Mozart’s Sister, as well as Constellation Records’ Ian Ilavsky), turns quickly into a symposium on what the Montreal music scene needs, turns quickly into an inner symposium on whether or not I should move here.

3. Arrive too late for Searching for Sugar Man, a documentary about Sixto Rodriguez; drink by the canal and eat Indian food in Old Montreal with my host, Julius, instead. Pretty sure the naan is buttered pita and the paneer is cheese curds from the dep.

4. Deerhoof at Cabaret Du Mile End. Mesmerized by guitarist Ed Rodriguez’s floppy hair and magic pants. He looks like the kind of guy that other guys hate because he looks like the kind of guy who would steal your girlfriend. Guys are right to hate him; I don’t. Show is great. Outside the venue, a young man is hunched over a pile of his own vomit, which looks quite a bit like the tomato soup I’m eating right now.

5. First of several Win Butler sightings. Every time Win Butler is sighted, everyone talks about another time they saw Win Butler. A conversation ensues about how nice a guy Win Butler is, and how famous the Arcade Fire really are. It’s a nice conversation, and the hints of bitterness are benign and incidental, little bits of shell in the egg white.

6. Arrive two hours early for Gang Gang Dance at the big church on St-Dominique, so friends and I pass the time by looking at photos of Ed Kowalczyk on Google Image Search. Around 1:32am, I follow @EDDIEKLIVE on Twitter. Turns out Eddie K Live released a solo album called Alive and got sued by his former band mates in Live.

7. Gang Gang Dance have a hypeman/”vibes manager”/Bez named Taka Imamura. He doesn’t play anything, but he holds up a drum for lead singer Lizzi Bougatsos to beat on; sometimes he dances with a garbage-bag flag. “Everybody could be a Gang Gang member,” he told The Fader. “I’m in them visually, [but] spiritually, everybody is a member.” Exciting news.

I don’t do drugs and I don’t really feel like I’m missing out on anything at shows like this, where the music is good enough to climb into and the vibes are well managed. But I’m always afraid someone will stop me to ask collegially which drugs I’m on, then laugh in my face when I tell them I’m only drunk.

8. Watch the video for Live’s “Dolphin’s Cry,” which I will hear in my head later while engaged in an intimate act. Watch the video for Live’s “Lakini’s Juice,” which unsettles me so deeply that I have to watch it ten more times. A friend digs up a 34-comment thread about the meaning of the song, which includes the line “I rushed the ladies’ room/Took the water from the toilet/Washed her feet and blessed her name.” Says WringWorm: “He’s trying to re-inact the perfection of Jesus by washing the feet of the girl like Jesus did with his Disciples, only with the sadness and sin of the secular world getting in the way, represented by having to use water from a toilet [sic].” Many commenters point out that Live is a Christian band, but lightbulb054 believes that LJ “represents a transition from the illusion of Christianity to the enlightenment of Hinduism.”

9. Mozart’s Sister plays a beautiful set at Parc de la Petite-Italie. I leave early in order to catch She Said Boom, Kevin Hegge’s Fifth Column documentary, at Pop HQ. But I get lost, and end up walking a full circle back to the park. By that time I have to pee badly, so I decide to suck it up and use an outhouse, which I forget to lock because I’m too focused on not touching anything. A good-looking guy about my age enters and makes a sound totally out of proportion to the sight of a peeing woman. He makes it again after he slams the door.

10. Climbing a steep metal staircase to the Grimes afterparty, we pass two women in black platform shoes and, I think, sunglasses. “How much money are you going to spend on drugs tonight?” one asks. “Fifteen,” says the other, which I gather is the price of “molly”—which, I have learned only recently, is MDMA.

I think you can judge a “moment” by its drug of choice. In the early ‘90s, when Julius was touring the underground loft circuit with his slam poetry ensemble, it was heroin, and his people were all mumbly; in the early aughts it was coke, and those people were mean; now it’s “molly,” and everyone’s super positive. I think. It’s sad to be a twenty-something talking about twenty-somethings and sounding eighty.

Jacques Greene, the guy Azealia Banks yells at in the “212” video, plays a great DJ set but I can’t dance too hard because I’m concerned about having left my jacket on the floor. If I lived here I could have left it at home and just dashed over clutching my sides. If I lived here I’d have friends who did drugs routinely rather than at Biannual Leisure Events, so I could just watch them do drugs and not have to wonder what it felt like. My friend’s friend lists the acts—Physical Therapy, Doldrums, Mykki Blanco, Cadence Weapon, Grimes DJ set—and announces that the party’ll be going until 7am, which seems less like party-fun and more like the kind of severe, molecule-altering fun they have at the screaming mud orgies Yoko Ono facilitated in a dream I once had.

My friend leaves to get a drink, but comes back empty handed because the police have shut down the bar. Turns out the very conspicuous cop I passed on my way back to the venue—I got pee-shy in the washroom lineup and left to go at a nearby McDonald’s—was, in fact, a cop. Mykki Blanco, who is doing a great set from atop a table, stops rapping. “We should go,” I say.

“Nah, just wait,” my friend replies. “It’ll all start again in a few minutes.”

The lights come on. “We should go,” I say.

On the street, we spot a woman dressed like Grimes who isn’t Grimes. Grimes is here, but I haven’t seen her. Maybe she’s dressed like a cop.

A squad car pulls up and more police start moving in, but the crowd hasn’t thinned at all. “When Torn Curtain got raided, that was awesome,” says a friend. “They took all of our mugshots. It was like a yearbook.”

“We should go,” I say.

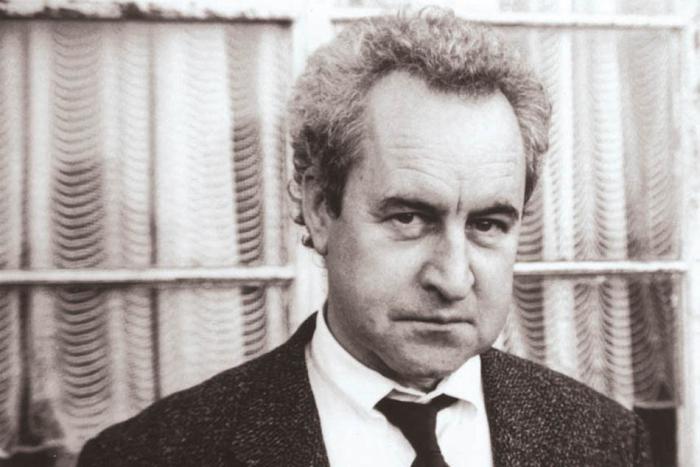

11. Bertrand Burgalat, at Cabaret Du Mile End, wears jeans hiked up to his belly button and tops them with a white belt and a charming blue polo shirt. I’d say he seems to sweat charm if he had seemed to sweat at all. He hops down into the audience; he invites the audience onstage. Danse, danse, danse, the song goes, and the crowd dances like it’s part of their physical therapy regimen. Shifting their weight to the left. Shifting their weight to the right. Gently swinging their fists. Occasionally adjusting their sleeves. After his set, Burgalat hops right into the crowd and starts shaking hands and chit chatting. I wish I spoke French, so I could know him.

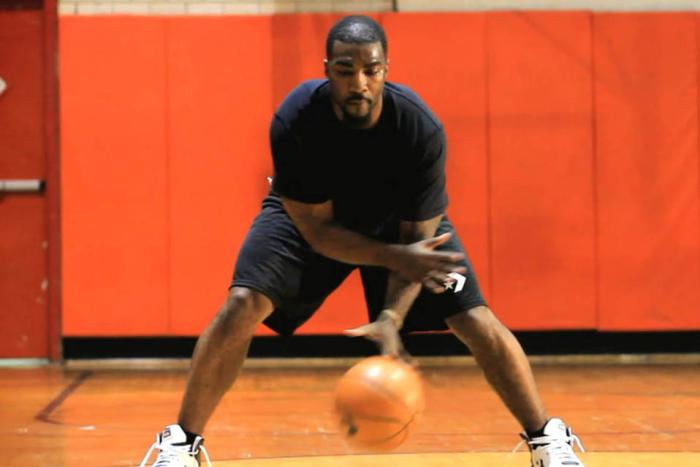

11. A Tribe Called Red at Eglise Pop are very good and extremely danceable. A gawky, bespectacled guy in a band T-shirt pushes up in front of me, throws some tentative bows and sort of crinkles at the waist like a thumb toy. I ask my friend if I look like that when I dance. “No, no, no,” she assures me. I resume dancing, a little self-conscious. The guy turns around and smiles, asks if we can dance together.

12. It’s raining when I leave my host’s apartment, but the sun’s coming out by the time I reach Mile End. From a friend’s balcony, we spot a man in a pink and violet suit walking up Jeanne Mance, saluting the sun with his body. My friends get “Mile Ended” several times before we reach Café Olimpico two blocks away, once by a couple straight from a ‘90s Stayfree Prima ad—the man looks like Joey Lawrence and the woman looks like Elizabeth Berkley—and once by a guy who looks like he plays in a band, and who most definitely does.

Everything that happens to us in Mile End is somehow endemic to Mile End, so I try to think of equivalents for Ossington Avenue in Toronto. Getting Ossingtoned is when three friends living at separate points on Ossington decide to stay home and watch a movie. Getting Ossingtoned is when you walk by someone you kind of know and smile and feel good about yourself for having done it. Getting Ossingtoned is when you walk by someone you kind of know and smile and they stop and talk to you and you regret having done it and never do it again.

13. Eat nachos at Casa Del Popolo because the pizza here sucks, which is the only thing Toronto has on Montreal besides raw ambition—and not by much, because most of the pizza in Toronto sucks, too. We head across the street to La Sala Rossa for Jacob Lusk & the R. Kelly All-Stars. Lusk is a former contestant on American Idol; the all-stars are local musicians who can play R&B. A friend and I run into a local musician outside of the venue, who tells us that Lusk is “a corpulent fellow.” Corpulence goes well with gold power pants and jewelry, and the set is brilliant: Lusk performs R. Kelly faithfully but with his own panache. I edge up front to dance to “Back and Forth,” the first hit on Aaliyah’s first album, which was the first cassette I ever bought. The great thing about being 26 is that your nostalgia is actually considered interesting. In a decade or two, we’ll all be Marge and Homer Simpson bumping hips to “The Hustle.”

14. Disco legend Jimmy “Bo” Horne takes the stage with backup dancers, a trio of early-20-somethings who look plucked from a catalogue modelling agency. They swing their arms limply from side to side and smile in an eerie, coerced way. Off to the sidelines is Horne’s manager, Beverly, whose presence is never explained. A few songs in, Horne pulls two audience members, a man and a woman, onstage to dance together. The woman edges away from her partner and tries to coil a leg around Horne; he shakes her off brusquely without missing a note.

My theory is that Beverly doped Horne up on Ativan before his flight from Tampa, letting him infer his location from customs, because Horne ad-libs the word “Canada” into almost every song he plays:

“Get down, get down in—CANADA!”

“Ain’t no party like a CANADA party!”

(During a disco cover of “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay”):

“Sittin’ on the dock of the—CANADA!”

Eventually, an audience member shouts that we’re in Quebec. “We must give much respect to Quebec,” Horne chants, off the cuff.

Between the strobe lights and the “DJ,” a 20-something dude in a T-shirt and flannel whose job is to hit “play” on a keyboard and then lean broodingly over the instrument until the next number, tonight feels like Canada’s bar mitzvah. Finally, Horne announces “Spank,” the track he’s best known for. (“I’ve been waiting all night for this,” yells the bearded guy behind me.) The DJ queues up the backing track and begins checking his phone.

“I love you,” Horne tells the crowd, for the 10th time tonight, with the flat intensity of a Russian dating scammer.

15. Get back to Toronto around 8:30pm, and rush to meet friends in Kensington Market for 10. We are going to see Nicky Da B, the New Orleans bounce rapper who closed Pop, but who I missed and opted to see in my hometown instead. I tell my friends about the awkward guy who asked me to dance at A Tribe Called Red and do an impression, but they don’t see a difference between the way I dance as him and the way I’m dancing anyway. When Nicky Da B starts, I keep dancing, while my friends hang back, seeming embarrassed. Around the third track, they tell me they’re going for pizza.