In post-war Japan, the world of comics was dominated by manga aimed at children and youth, none more influentially than the works of the master cartoonist Osamu Tezuka. As the 1950s ended a new genre began to take form, striving for stylistic realism, mature themes and grimy settings: gekiga, or “dramatic pictures.” Gekiga was coined by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, and the young artist’s bleak, economically paced stories helped define it. Almost unknown on this continent for decades, he’s enjoyed a rare breakthrough late in life, after the Montreal publisher Drawn & Quarterly began translating and collecting his comics in 2006.

Four years ago, they brought Tatsumi to the Toronto Comic Arts Festival to fete his dense, oddly subdued, Tezuka-haunted graphic memoir A Drifting Life. That book provided the skeletal structure of Tatsumi, a new animated adaptation and tribute directed by Singapore’s Eric Khoo, which starts its run at the Lightbox tonight. It also gave me an opportunity to interview the man himself. Our translator rapidly parsed meanings as Tatsumi’s spoon sagged beneath a melting ice cream sundae. That Q&A was published on the now-dormant blog Comics Comics at the time, but Khoo’s film seems like a logical excuse to revisit it.

Reading A Drifting Life, one part that immediately struck me was your mention of negative news coverage about what the young artists were drawing—the “vulgar manga,” a.k.a. gekiga. Could you describe that in more detail?

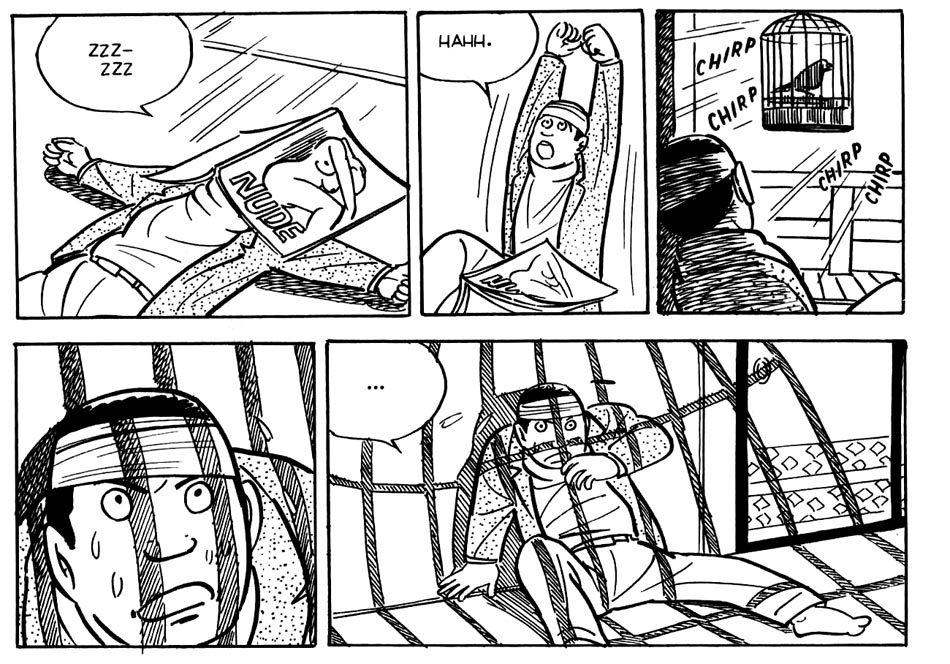

The parents were really up in arms about these bad books. Manga at that time was different than it is now. It was friendly manga, so little kids could read it too… On the page you have the same number of panels, the people move from left to right and they’re all the same size and it all looks the same on the page… There was no movement or anything like that. We took inspiration from movies, doing zoom shots or close-ups. Using the camera. We wanted to use these techniques in manga, really violent movement. We were trying to move the panels in a realistic kind of way, to make work without lies, true work. In work before, for example, if a samurai cuts someone—

There’s that great line from the book: “If a person is stabbed, they bleed.”

Even if a person’s head was cut off and fell to the ground there was no blood, nothing came out. Like an onion. [Tatsumi chuckles] Even if the head was separated from the body it looked like the head was still alive… You couldn’t really say that would have a bad influence on kids. So we came in and took a bat to the whole thing. We did more realistic work, more photographic almost.

In Tezuka Osamu’s work animals speak, and people answer them. I think that’s probably the influence of Walt Disney, but when we wrote mysteries it’s no good if animals are talking. If a dog watches a murder or something and you know that the killer escapes—if the dog says “Oh hey, that’s the murderer,” that’s not really a good thing. So we didn’t draw things like that. We drew realistic things, like the strong feelings of happiness or sadness that people have. Close-ups on the main character to really show their anger—when you’re looking from far away there’s not really a lot of power in that angle. When you’re drawing a work like that, of course you’re going to see blood. If you compare that manga with the children’s manga up to that point, they just couldn’t forgive – they wouldn’t accept that kind of manga. The [parent-teacher associations] were like, “let’s just not buy it.” A lot of them sprung up all over Japan to boycott the work.

That was only a couple of years after essentially the same thing happened in the U.S., with parents and politicians and other figures in society trying to ban or boycott violent crime comics.

Yeah, it was the same thing.

I’ve heard that you’re already working on the next volume of your memoir and have a few hundred pages done, so I assume you’ll be doing that for the foreseeable future. But I’m wondering if there’s any books from before, after or during your gekiga period that you’d like to see reprinted… I want to see the one with the giant snakes.

I have so many. If you put my short stories and my longer volumes together, I’ve written about a thousand pieces. I’d like to [recover] as many of them as possible. I plan on writing the continuation of A Drifting Life within the near future. If I don’t do it soon—I don’t have that much life left, you know? [Tatsumi laughs] I gotta do it as soon as possible.