Superlatives fail Love and Rockets. It isn’t right to call the 31-year-old comics series “groundbreaking,” because there wasn’t much ground to break when it first arrived. “Game-changing” is a little better, but it would suggest that the comics game has changed since then—as far as stories about women and subcultures and hybrid identities that ring true—and it hasn’t.

Love and Rockets came out of nowhere in 1982. A series of parallel narratives by 20-something Chicano brothers Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez from Oxnard, California (and occasionally an older brother, Mario) the stories were propelled by a punk ethos and unprecedented-in-comics concern for characterization. And in the world of L&R, women were in charge.

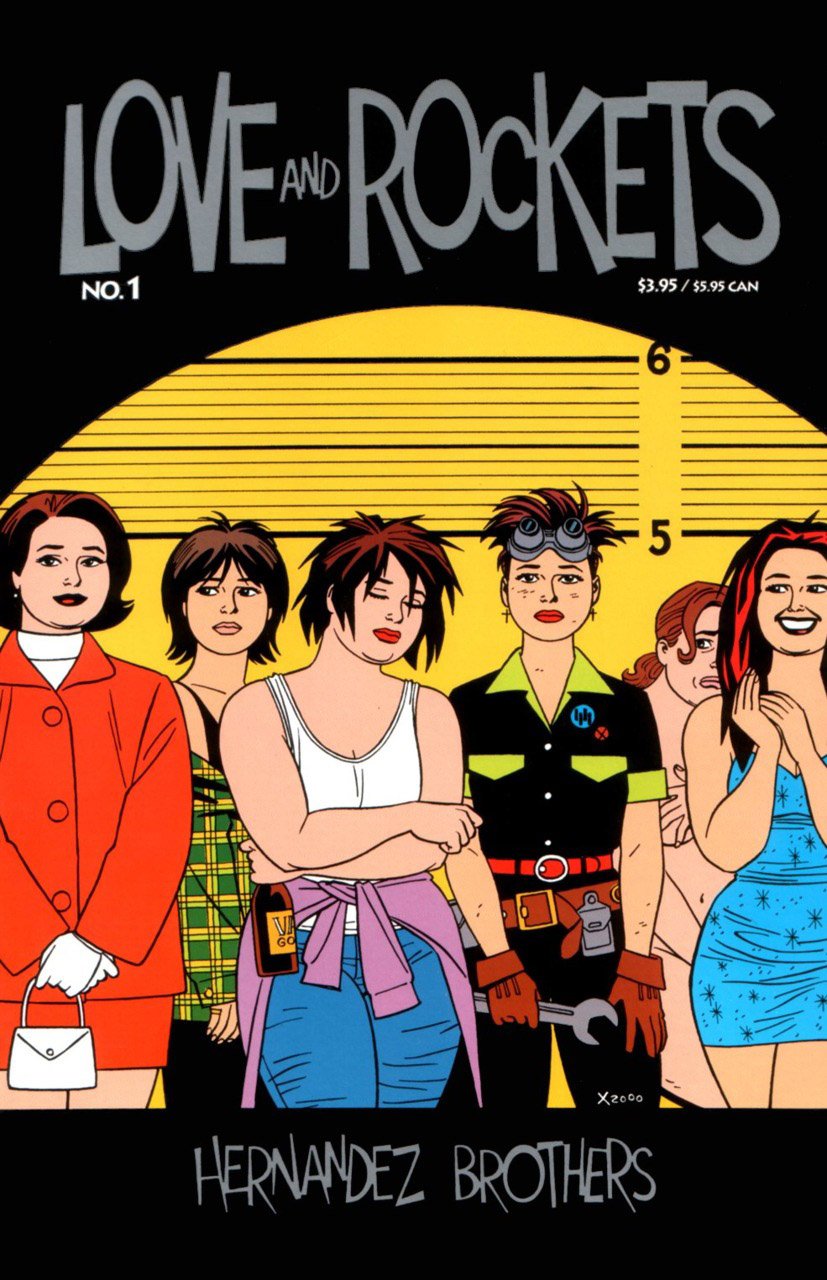

Gilbert, or Beto, dealt magic realism through a fictitious Central American village named Palomar (governed by a busty, take-no-bullshit babe named Luba) while then 22-year-old Jaime generated the Oxnard-esque town of Hoppers, populated by a cast of wacky, sensitive, and utterly relatable characters called Las Locas (The Madwomen) whose paths and sensibilities have developed in real time since the series began. The heart of Las Locas is Maggie (full name Margarita Luisa Chascarillo), who began the series as a teen “prosolar” mechanic repairing rocket ships and robots; after Jaime abandoned those early sci-fi trappings, Maggie continued as a wrestling manager, wanderer, and eventual apartment complex manager in the San Fernando Valley. She’s vulnerable but tough, having been raised in part by her ex-wrestler aunt Vicki Glori, and schooled in punk by her best friend Letty, who died in a car crash when the two were in high school.

I met Maggie the Mechanic in my early 20s after unwittingly copying a haircut sported by her friend and sometimes-lover, a tsunami on skinny legs and (lousy) punk bassist. “You look just like Hopey,” my buddy pointed out, and when I realized my cartoon doppelgänger was a fellow half-Latina weirdo, I figured it was meant to be. I had no idea what I was taking on: catch-up on a saga that’s been unfolding since before I was born. Neither did I expect these dude-made female characters to seem like actual people. “They’ve got a life of their own by now,” Jaime told me when I asked, during a recent phone conversation, whether his characters still felt like made-up entities from his own brain. “I picture them as people who live in my town, and that does help me make them seem human.”

The Hernandez Bros haven’t had much downtime lately, in between touring for several 30th anniversary retrospectives, and work on L&R: New Stories #6, the latest in a collection they’ve put out annually since 2008 and due in September. Jaime kindly let me interrupt him to talk about the Locas legacy.

You’ve been writing Las Locas for over 30 years now. Is it easier or harder to write their stories now than when you started?

It’s both easier and harder. The hard part is keeping it fresh, keeping the stories fresh and original when it’s been 30 years of writing these characters over and over again and trying to come up with something new every issue. The easy part is that I know the characters so well, so they can basically write their own stories most of the time. That’s very helpful.

Why do you think you’ve kept with Maggie and Hopey and the gang so long?

Oh, I just like them. Obviously I like doing Maggie most. I know her the best of all of them. She’s fun to write. Anything I put her in, I know what she’s going to do and where she’s taking me. We’re kind of growing old together. It’s like my old friend, seeing what she’s up to. I have to look at it that way, otherwise [the characters] won’t plop on the page the right way. Usually I’ll write the characters that I like, because I enjoy watching them mess up or succeed or just interact.

Why do you think you’re able to write women so well?

That’s the question I’m never able to answer. There have been theories over the years. My brother and I have talked about it, and we’ve come up with these ideas like: “well, we were raised by our mom ‘cuz our dad died when we were young, so we saw the world through her eyes.”

The first time a woman told me I was doing it right, I was like, “cool.” I think most of it comes from the fact that I just like women, period. I like the way women are, and I like the way women look, obviously. Along with that comes responsibility: if I want to draw these curvy women, I have to back it up. I gotta put some people in there. And that was really important to me really early on, even way before Love and Rockets when I was drawing my own little comics for myself as a teenager. Anyway, when someone told me I was doing it right, I was like, “Alright, full speed ahead!”

You know, I’m very conscious of doing it right, but at the same time, I’m trusting my instincts that these are people with feelings and brains just like everybody else. I try.

What is it about women’s stories that attracts you?

I would say a lot of it has to do with just my experience of knowing women, being friends with women for so long. I like the way women react to situations. Guys in a certain situation mostly try to keep it cool, keep their cover, keep things in control. With a lot of women I know, you get eight different reactions to a situation. One is keeping control, another one is flying off the handle [laughs], because women show emotion more. So you get a lot more opportunities to write a situation and then a reaction to a situation. It’s just how I see it through my eyes. I’m not a woman so I don’t know what’s going on, but I just really enjoy watching a woman react to any given situation, whether it’s calm or emotional or whatever.

Do you think that women’s stories are easier to tell, for you?

No. But they’re funner. [Laughs]

You’ve talked about people giving you flack for Maggie’s weight gain over the years [from anxiety-induced overeating], and you responded along the lines of, “Well, that’s what happens in real life.” Have you gotten flack for other “real life” details in characterization?

One other criticism I got early on was about my lesbian characters. It was basically, “That’s not how they do it.” And I was like, “How do YOU know?” That was the only other flack I got, in terms of creating my characters. Oh yeah, and someone thought my men were dullards, these weakly written background characters. And I once again just shrugged and said, “Well, you’re just not used to women being in charge.”

I can’t think of another series, really in any medium, that lays out such a broadly diverse cast of characters the way Love and Rockets does, and so matter-of-factly. Is that something you’re conscious of?

I became conscious of it when I found out that it’s rare. Then I thought, “Hey, we did this comic. I thought you guys were gonna all follow. I thought things were actually gonna open up here.” When I found out there was no interest on other creators’ parts, Gilbert and I just said, “Well, if they’re not gonna do it, I guess we have to.”

It’s just really natural for my brother and I to do stuff like this. It seems like a no-brainer. But apparently it’s a brainer!

Did you feel like you were breaking ground, or was it just like, “These are the characters I’m making,” without thinking about where it fit into the landscape?

I thought I was breaking ground in comics. In 1982, there was so much opportunity for something like that, because there was nothing—or almost nothing—like that in comics at the time. We kind of took advantage of that, I guess. But I didn’t realize that even out of comics, there was very little. I didn’t notice. But I thought, “Well, this is real life.” If it’s real life you don’t have to apologize for it.

Do you think L&R will continue indefinitely? Do you see an end?

No. We plan on doing this as long as we can. The only thing that will stop us is our health. Or if we end up having like two readers, that’s something to think about. But we’re here for the long run. When you finish one, you do the other. Keep going, keep going, keep going.