Last week, Islamic State militant leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was caught on tape railing against western decadence while seemingly wearing a luxury wristwatch (his supporters quickly countered that the watch was, in fact, a cheaper Saudi Arabian make). That same week, the Wisconsin Republican party attacked the Democratic gubernatorial candidate for calling for an end to out-of-state campaign donations while accepting a million bucks herself, the British Education Secretary was criticized for demanding low-cost schools and then approving a fancy new headquarters, and Ottawa sex workers briefly considered outing a specific group of clients—Conservative MPs currently pushing through a harsh anti-prostitution bill.

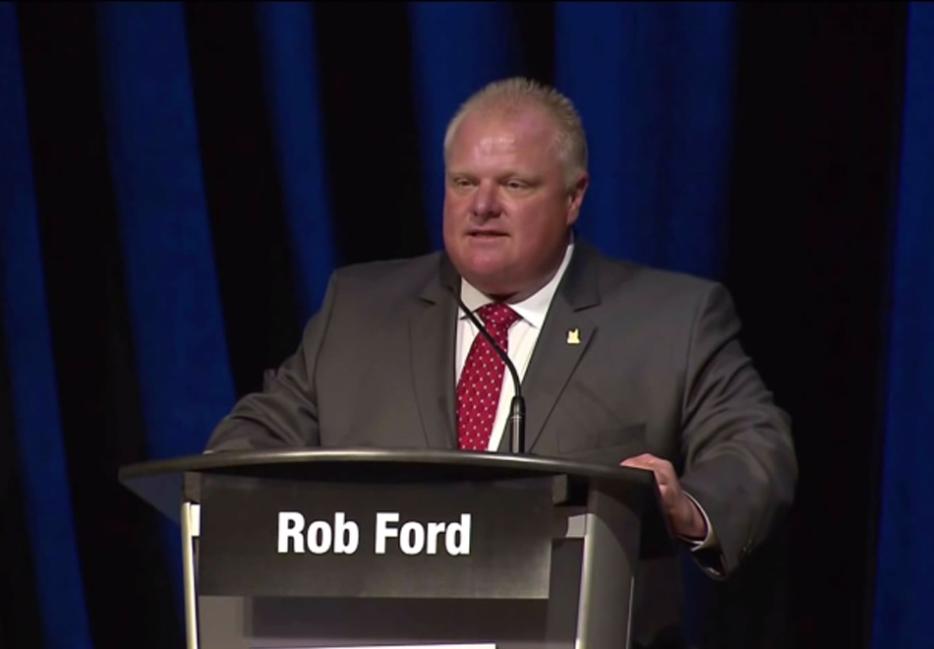

Throughout all of this, Rob Ford continued to live and breathe, speaking words and performing actions in perfect opposition to one another, rumbling through an election campaign as if propelled by the electromagnetic force of his perpetual hypocrisy.

Of all moral offenses, hypocrisy is perhaps the most galling. It is the transgression that demands to be called out. There is nothing more enraging than the politician who doesn’t practice what he preaches, nothing more satisfying than the gotcha moment when a self-righteous scold is revealed as a charlatan.

The hypocrisy of the powerful, whether mayors or terrorist leaders, has been well documented; the cliché about power corrupting exists for a reason. In a study from a few years ago, though, researchers set out to prove a direct link between moral hypocrisy and power. The paper, by professors from Northwestern University and Tilburg University in the Netherlands and published in the journal Psychological Science, attempted to take the powerful and measure “the discrepancy between the moral acceptability and appropriateness of one’s own moral transgressions and other people’s moral transgressions.”

In three related experiments, researchers first primed people to either feel powerful or powerless using a variety of strategies. In one experiment, they created a mock bureaucratic organization and randomly assigned participants to act as either prime minister or as a low-level civil servant. In another, students were asked to remember a moment when they felt powerful or a moment when they felt powerless.

Next, participants—in what they were told was an unrelated experiment—were presented with one of three moral dilemmas. Let’s say you’re late for an appointment—is it OK to exceed the speed limit if there isn’t much traffic on the road? How immoral is it to omit additional wages from a tax declaration? What about if you find an abandoned bike and you’re broke—is it alright to keep it, or should you bring it to the police?

In each experiment, half the participants were asked to rate how acceptable the actions were for themselves, while the other half judged how acceptable it was for others. Again and again, across the experiments, researched found that the participants primed to feel powerful were hypocritical, lenient about their own transgressions while highly critical of others. The powerful imagined that keeping a stolen bike was more acceptable for people themselves than for others. Those in low power positions showed no signs of hypocrisy. In fact, in two experiments, they seemed to judge themselves more harshly than others.

In a final experiment, the researchers attempted to remove the element of entitlement from the equation. Here, participants were asked to write about a time when they were in a position of power, but half of that group was asked to recall a time when that power was illegitimate and they believed they were not entitled to that position. As expected, the powerful and entitled again demonstrated hypocrisy. The illegitimately powerful, however, demonstrated no such double standard. A stolen bike was as immoral for themselves as for others.

The cause of heightened hypocrisy, the researchers argue, stems from two separate characteristics. Our judgment of people is not solely about whether their actions have been morally objectionable; it’s also based on factors such as feeling entitled to judge others. The powerful are more likely to criticize others, to hold strict moral guidelines, because they feel it is their right. At the same time, previous studies have shown that the powerful are “more focused on the potential rewards of any action than the powerless are and therefore tend to follow their self-interest more.” Power can insulate you from social disapproval, one of the great enforcers of social norms, making actors feel above the petty concerns of ordinary people. It’s this sense of entitlement that creates both the tendency to judge and the feeling that you are above considering minor transgressions—the definition of hypocrisy.

Studies Show runs on Thursdays.