I learned a very valuable lesson about the power of an image a couple of weeks ago when Twitter handed me my ass on a platter. As the dissenting voice on a panel discussing Janet Jackson (who, after a four-year hiatus and declining record sales, released a new single and is set to embark on an international tour next year), longtime fans came after me for openly questioning her relevancy. Could she remain as important as she was during her heyday (1990-2004) among the current throng of pop stars?

Based on the blistering replies I received after the panel, the answer is yes. Janet is iconic, and image and iconicism are important, specifically to black women. The representation of black women in media, from Oprah Winfrey and Maya Angelou to Beyoncé and Rihanna, creates hope that we, whom poet/author Zora Neale Hurston once described as the “mule uh de world,” can inspire an alternative view of ourselves: individual agents instead of a monolithic group.

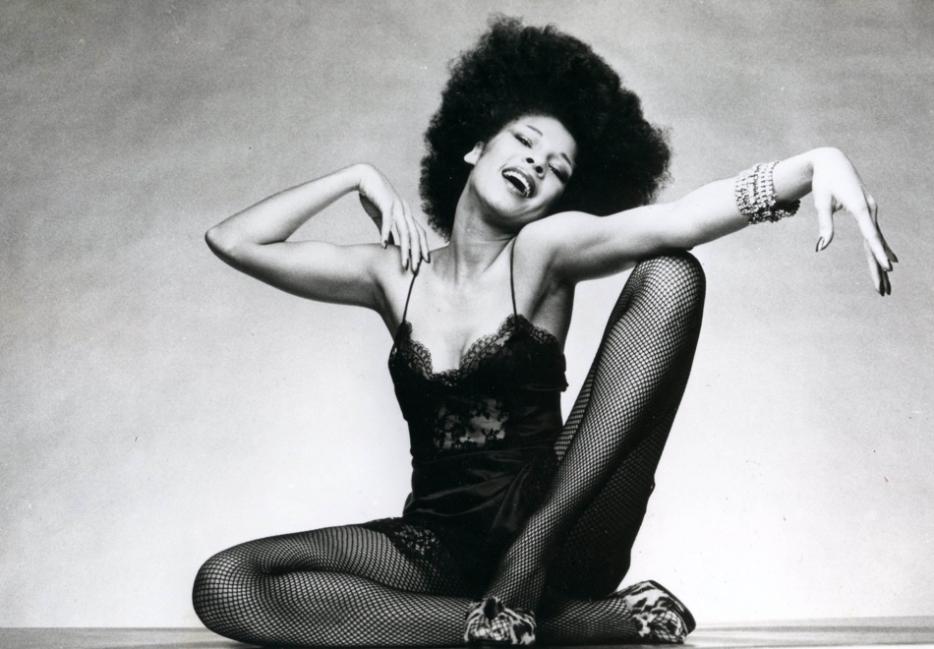

Betty Davis’s career was short-lived, but the iconic status of the rock singer, who celebrated her 70th birthday at the end of July, remains strong. Davis released three studio albums in the early-to-mid-1970s and then faded into obscurity. Unlike Janet Jackson, whose childhood role as “Penny,” a victim of child abuse on Good Times, positioned her early on as a beloved figure (which would largely continue throughout her career), Davis’s image from the get-go represented a sexually subversive, deeply independent persona that could be intimidating to some. “I’m very aggressive on stage, and men usually don’t like aggressive women,” she told Jet magazine. “They usually like submissive women, or woman that pretend to be submissive.” With song titles such as “He Was a Big Freak” and “If I'm In Luck I Might Get Picked Up," her music has been described as “Raw Gut Bucket Funk”—deep, groovy, Southern-fried rock that was so dirty and rough, a commenter responded to a music critic who challenged her adulation by writing, “I feel really sorry for you. You've obviously never had a night in a hotel room with an amazing woman (or man), a bottle of Jack Daniel's and a load of blow, because that's what this music sounds like.”

But until 2007, when the record label Light in the Attic re-released her albums, Davis was more commonly referred to as a rumored lover of Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton or for her brief and tumultuous marriage to jazz innovator Miles Davis. When Betty Mabry met Miles Davis in 1967, the 22-year-old model was a mainstay in New York’s celebrity circles and hip to the contemporary music scene. She has since been credited with introducing Miles to funk and rock music, most notably the aforementioned Hendrix, then a burgeoning star. In a 2010 interview with The Guardian to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Bitches Brew, Betty, who suggested the provocative title, revealed that Miles, who had a predilection for “little girls” (he was 41 when they met), had a violent temper, which ended their one-year marriage. In his biography, he accused her of having an affair with Hendrix, writing that she was “too wild” for him.

*

Steeped in classism, sexism, and internalized racism, respectability politics (which Jackson experienced after her infamous Super Bowl XXXVIII wardrobe malfunction) has been a common deterrent for black female artists involved in non-black-centric art forms, such as rock n’ roll. The fear is that a questionable image will tarnish the morals of the next generation of black women and deter from “uplifting the race.” It was the force that led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to deem Davis’s music as inappropriate for black consumers.

Davis had been singing prior to meeting Miles, but it wasn’t until after the brief marriage ended in 1968 that she gathered limited attention on the Billboard charts for two singles. She was able to get three albums released on tiny, independent labels (a fourth album of previously shelved material is now available through Light in the Attic). Maureen Mahon, author of They Say She’s Different: Race, Gender, Genre and the Liberated Black Femininity of Betty Davis, and one of the few people to interview Davis in the last two decades, suggests the public backlash she received played a big factor in her retreat from the spotlight. The combination of lyrics such as, “I used to whip him / I used to beat him / oh, he used to dig it… Pain was his middle name” from “He Was a Big Freak” (rumoured to have been inspired by her relationship with Miles), sexually provocative attire, and a raunchy stage presence raised enough eyebrows within black communities to cause a public shunning. According to Mahon, radio station boycotts, a public denouncement from the NAACP, and weak record sales made it nearly impossible for Betty Davis to build a career performing the music she wanted to.

In his biography, Miles Davis accused her of having an affair with Hendrix, writing that she was “too wild” for him.

“If it hasn’t been culturally appropriated by whites, we don’t know how to accept it,” says Brooklyn-based singer Nucomme, Seven years ago, she was relaxing at home with her husband watching a documentary on Miles Davis, when a brief mention of his wife, accompanied by a snippet of Betty Davis’s music, suddenly appeared onscreen. Nucomme’s ears perked up. “My husband did some research online and found the song, ‘Lone Ranger.’ In 2008 there were only two songs of hers on YouTube, but when I first heard it, I started levitating—it was so sexy,” she says. That moment sparked several years of researching the reclusive singer that culminated in Betty’s Story, a multimedia musical tribute that Nucomme and her seven-piece band, featured musicians, backup singers and four burlesque dancers have performed for New York audiences for five years. Davis’s album covers, stock photos, and the few images of her performing in cramped clubs are prominently projected on the backdrop as Nucomme and her singers perform Betty’s greatest hits. The dancers are resplendent in outrageous and provocative outfits that are carefully crafted not to imitate the crazy get-ups the singer once wore, but more to represent the era and to celebrate the black female body. Low-cut tops (sans bra), skin-tight skirts, leggings and enough makeup to make Dolly Parton nervous demonstrate liberation from social conformities that hinder self-expression.

Nucomme says that while her tribute to Davis has been positively received by audiences, getting (and keeping) it on the stage has been a challenge. “I’ve not been invited back at certain venues. I’ve been harassed; people have threatened to call the police,” she says, suggesting that event bookers who were not fully aware of the components within her production aren’t interested in staging it once they’ve seen it live. “Black women shaking their ass and wiggling their natural body parts ... it's too much for some people to take. Again, it's not the audience; it’s what’s going on backstage.” Nucomme incorporates burlesque dancers into her show to emphasize the importance of Davis’s stage presence and her hypersexual lyrics, and the response illustrates a contradiction in how black female sexuality is perceived. “It’s like the whole conversation about twerking. The only reason black people are scared of these things is because we don’t have the luxury of getting work,” she says. “You have white people out here teaching twerking classes, making thousands of dollars. They are fucking winning. Our young black girls are twerking and getting their ass beat on YouTube.”

*

Outside of granting a handful of interview request to support the re-release of her albums, Davis chooses to remain out of the spotlight. The ramifications stemming from the dissolution of her marriage, the death of her father, and the loss of good friends such as Hendrix (whose untimely death from drug use during her heyday was an important factor in her leaving the industry) have made her a private person. When researching Betty’s Story, Nucomme reached out to her family: “She’s no fool. She likes her anonymity and she likes being remembered for the way that she was, but she went through a lot.”

Davis wrestled with the way non-black record executives and record companies viewed her marketability, something that contemporary black women rock artists still face. But Davis’s influence can be felt in the present and future generations of black female alternative, funk and rock artists, such as Toronto’s SATE, Skunk Anansie’s vocalist Skin, Tamar-Kali, N’Dambi, and even FKA Twigs—all of whom exude a self-possessed, raw honesty that demonstrates their insistence on being judged for their individual traits and not for what is expected of them. These women are creating innovative work, but they’re still competing with artists like Jackson, who fit more neatly into the racial and sexual categorizations that drive the music industry. Davis was befallen for refusing to conform to an image and attitude that satisfied both black and white communities, but thanks to the advent of the Internet and the ability to release music outside of major record labels, this generation of black females at least has more opportunities to get music to the masses, “too wild” or not.

In the upcoming documentary, Nice & Rough: Black Women In Rock, veteran hard rock singers such as Joyce Kennedy of Mother’s Finest (who, in 1992, released Black Radio Won’t Play this Record) suggests that many executives are only willing to take a chance on one alternative black person at a time. “[A record executive] looked me in my face and he said, ‘we don’t need another black woman in rock n’ roll,’” says Siedah Garrett. Known for her vocal duos with Michael Jackson and songwriting skills (having worked with Quincy Jones and Selena Gomez), issues surrounding marketing appeal have hindered Garrett as a rock artist. “With a face like mine, hair like mine, and rock music … [industry executives] just couldn’t get their heads around that concept. I just didn’t fit what they thought rock was, but for me, I didn’t fit what R&B is.”