I want to tell you about my favourite music video of all time.

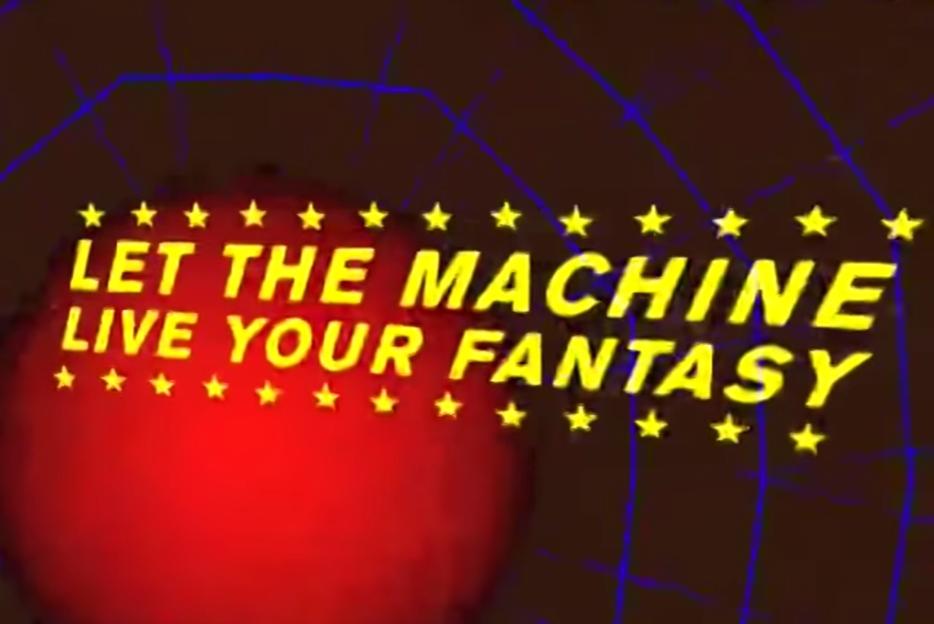

A woman is having an orgasm, or a seizure, on the back of a tan centaur. Another woman, and admittedly, it is hard to tell because she is made of a series of flat planes that are too few in number to truly sell a particular gender, is lying on the floor, quivering with excitement as a metallic bear falls towards her and then through her and the floor below. A man, made up of a few more surfaces so it’s easier to tell, and also he is naked, violently escapes a large orb like the last son of Krypton. On their own, these images are nothing—flotsam bobbing along the soup of the Internet. Together they’re slightly better, flotsam plus. But then you notice the chevron quietly explaining each act—CENTAUR STYLE, DESCENDING BEAR, EMERGING FROM SPHERE—the watermark holding court over the proceedings, FETISCHPRO, suggesting that what has just happened is still happening, isn’t a fevered Internet hemorrhaging content but something darker and more familiar. A product demo.