For the better part of a decade, groups of very smart people have been teaching cars to drive by themselves. Not literally, of course. There’s no driving school for 16-year-old teen Intel processors borrowing their parents’ beat-up old sedan. Rather, we do what we often do—throw a bunch of data at the problem and hope for the best. Immutable knowledge of curb heights, GPS coordinates and encyclopedic road sign placement isn’t exactly driving in the Steve McQueen sense, but it’s data a self-driving car can’t drive without.

Researchers at IBM, meanwhile, have been feeding the Jeopardy!-winning supercomputer Watson data of a different sort: molecular knowledge of the chemical composition of food, a computer that can cook. Here too, Chef Watson’s understanding of food isn’t the same as ours—all smoke and mirrors in the absence of taste. It knows what ingredients work well together chemically, but that doesn't mean its recipes are necessarily good. Burritos with chocolate or coconut-flavoured fish and chips? Computers! They’re just like us.

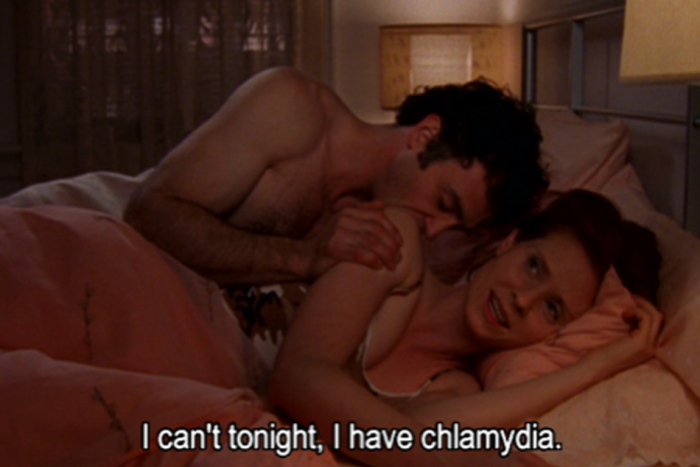

And so, it’s only a matter of time before our attempts at creating digital simulacra of human behaviour extend to relationships and sex, like a computer that can understand the complexities of our most intimate wants and needs. Where will we get the data for that? As enjoyable as it would be to watch people perform awkward first dates in green-screened studios while dressed in ping-pong motion-capture balls, the reality is that this is probably unnecessary. The data already exists. It’s called online dating, and hidden within the plaintive messages and carefully crafted profile pages are innumerable data points—however flawed—on human relationships, sex, and love.

Christian Rudder, the co-founder and president of the dating site OkCupid, wrote Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One's Looking) about the insights he’s been able to glean from user activity on his site. From 2009 to 2011, Rudder ran a dating research blog for OkCupid called OkTrends, including uplifting posts such as “Rape Fantasies and Hygiene By State,” and “Don’t Be Ugly By Accident!” (The latter offered “statistical proof” that “iPhone users have more sex.”)

In the same way that we feed Watson old recipes and data on molecular bonds, the personal data we’ve set loose upon the Internet—from our OkCupid personal profiles to the most benign of Google searches—is most likely the way in which an artificial intelligence will learn about us.

It knows what ingredients work well together chemically, but that doesn't mean its recipes are necessarily good. Burritos with chocolate or coconut-flavoured fish and chips? Computers! They’re just like us.

When a user sends a message to another user on OkCupid, for example, the length of a message, number of edits, and time it takes to compose that message are tracked, and that data is retained. Rudder then correlates this data with response rates to illustrate the sweet spot between stream-of-consciousness messages and those who overthink. In one section of Dataclysm, he identifies the most typically used words on the public profiles of White, Black, Latino and Asian men and women on OKCupid, concluding that Belle and Sebastian is maybe the least-Black band around, and that White women are more likely to include the words “Phish,” “riding horses” and “I’m a country girl” in their profiles than others. Elsewhere, Rudder finds that Black people are, relative to other races, “unappreciated by non-Black users,” and receive “three-quarters the affection.” He also finds that “the vast majority of both male and female bisexuals seeks [seek?] exclusively one sex or the other on the site.”

It is, according to Rudder, the human id laid bare: what we say we’re looking for, and what we’re really looking for.

But if Watson and Google have taught us anything, it’s that such data has its limits. We use smoke and mirrors as a way to take imperfect data and produce a reasonably human-like result, but we’d still never mistake it for one of us. If you want to hear how poorly this process plays out when we try to reduce the basics of human relationships into data-points, all you have to do is pick up the phone.

Telephone support fills me with dread: with each passing year, it becomes harder and harder to speak with an actual person. Instead, I’ll be greeted by faux-human operators with wholesome-sounding names like Becky or John. “Tell me what you’re looking for!” Becky cheerily intones. “What are you calling about today?” asks John, feigning interest. And I mash “0” until I hear a verifiable human being on the other end of the line.

Companies try to discourage this as much as they can, because it’s cheaper to have the computer solve your problems than hire enough human operators to keep up with demand. Plenty of money is spent on making these faux-human interactions better—more human. They speak casually, like you’re having a chat with someone you already know. They apologize when they don’t quite understand what you’re saying. It’s all very natural. Computers! They’re just like us.

Of course, while these faux-human operators are hitting all the right social cues in theory, there’s something about the delivery, the back-and-forth volleys, that always feels off. They’re not perfect, because like Watson or Google’s self-driving car, they rely on a very limited set of data on how people communicate in the human realm.

While we can certainly learn a lot about people from their activities on online dating services—even, as Rudder’s book asserts, “Who We Are (When We Think No One's Looking)”—such data is hardly complete. Just as teaching a car how to drive around California doesn’t give it license to drive through the rest of the world, nor does teaching a computer a library of recipes make it a world-class chef—you probably wouldn’t want to date an A.I. who’s fed a diet of online dating data.

After all, what would a service created to bring people together know about breaking up?