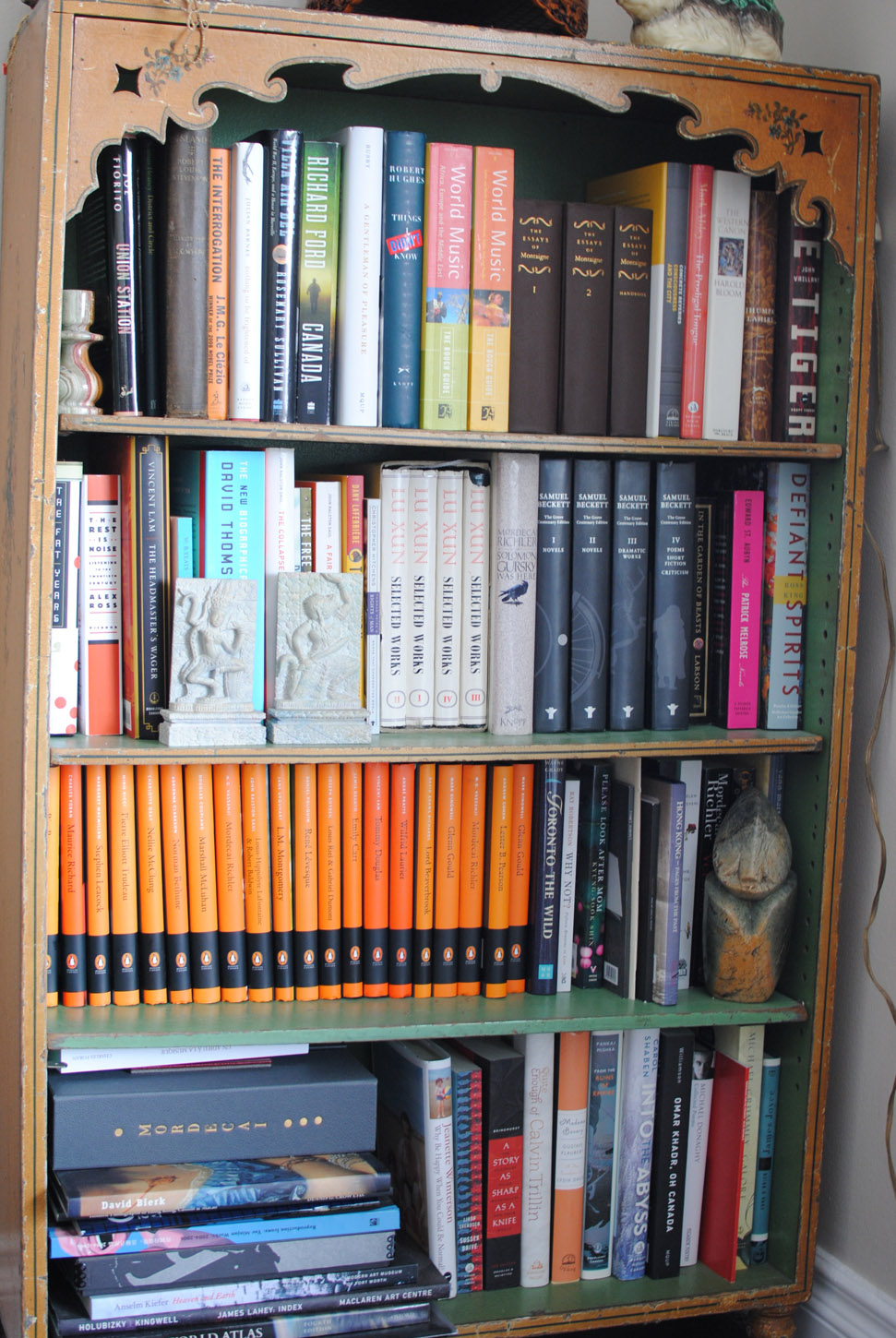

Shelf Esteem is a weekly measure of the books on the shelves of writers, editors, and other word lovers, as told to Emily M. Keeler. This week’s shelf belongs to Charles Foran, the author of 10 books, winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award, and current president of PEN Canada. Foran has but one actual bookshelf in the midtown Toronto apartment he shares with his wife, but there are books and journals gracing almost every horizontal surface. His desk is in a second bedroom, across from a table laden with approximately 150 books. The rest of his collection, he laments, is still in his previous home in Peterborough.

Outside of the books related to current projects, there are only a few books that I sort of travel everywhere with, and you’re looking at them there. These are sort of totemic books for me. The complete works of Lu Xun—probably my next book is about that man. He is China’s most important writer, enormously influential in China, but almost entirely unknown in the west. Which is odd. And Beckett. He was sort of the writer that awoke me to great art. And I’ve always loved Montaigne’s essays. As I said, I always keep those books nearby, on the off chance that the proximity makes me a better writer. Unlikely though that is.

What you have to do with John Banville, I’ve learned, and I’ve learned it the hard way, is you have to find the areas concerning writing and literature that interest him professionally. Because he is not your regular kind of plot and character guy. I first interviewed him at a reading series perhaps 15 years ago, and it didn’t go particularity well. The next time I met John Banville was while I was in Hong Kong, just after he’d won the Booker. I used to help run the Hong Kong literary festival while I lived there, and he was in a slightly different frame of mind, having won the Booker. And we got on very well, and traveled together to Shanghai.

I began to realize that by his nature he’s a very intense man, who really wants to talk about important things. So you don’t ask about the characters in his books, and you don’t ask about the story. Once you figure this out, you ask him about language, the experience of reading a novel, and what the aesthetics of it are. You ask him, if you feel comfortable, about even deeper things. We did a stage event in Hong Kong, and we’d already talked a few times, and he said, let’s just talk like it’s the two of us. And we circled around a preoccupation in his work—and it’s the reason I’m teaching his work in this course, because it’s a preoccupation of Irish literature in my opinion—which is self awareness, self-consciousness. We basically spent 45 minutes talking about the vexing matter of humans being intensely self aware. And if you look at his work, it’s all about that. His characters are always hyper aware of their selves, hyper aware of their consciousness, and troubled by it.

Another writer that I adore and think a highly important writer is a man named Timothy Mo. I don’t have any of his books here in front of me right now, they’re unfortunately still in Peterborough. He was part of what they call “The Revenge of the Empire Generation.” So Rushdie, Ishiguro—Martin Amis is sort of representing the establishment there. But of that whole crowd that came out of the ‘70s and ‘80s UK, Timothy Mo was in many respects the most brilliant and mercurial of the bunch. He was Hong Kong born, of mixed parentage. Came to England to a private boarding school, that whole kind of narrative. The Pico Iyer narrative. Mo began publishing novels in his 20s, and three of his first four books were shortlisted for the Booker. The Monkey King was published when he was 29. He wrote an amazing historical novel called Insular Possession, about Hong Kong. And then an even more remarkable novel about East Timor called The Redundancy of Courage. He had this amazing career going, he was acclaimed and spoken of—with Rushdie and Ishiguro—as very much a leading light in this new kind of post-colonial literature. And then Timothy Mo exploded his career. He blew it up.

For his next book he rejected a considerable advance, and decided that he’d had it with publishing, and the attitudes of the British. He self-published this novel, Brownout on Breadfruit Boulevard, in 1995. It had an especially aggressive and purposefully offensive opening chapter, describing a sexually degrading act between a teenaged Filipino prostitute and an elderly British man. It was designed to sort of say that this is what the west has done, this is colonialism from my perspective. The novel sank. He had turned down all this money, and he disappeared.

For the longest time nobody knew where Timothy Mo was. He self-published another novel in 1999. And then he disappeared for another 15 years. And just this past spring he self-published another novel, Pure. I thought the novel was so good and so wild and so him that it would get on the Booker list. In my opinion he’s a great novelist, and he’s behaving in the most extraordinary manner. And he continues to behave that way, and it’s pretty clear from people I’ve spoken to that if he wanted he could certainly be published on a major house again. But he doesn’t want it. As far as I can tell he didn’t do a single event to promote this latest book. The book’s a wild thing.