Among marine biologists, St. George’s Bay—a jagged, triangular body of water near the southwest corner of Newfoundland—is better known as the Whale Trap. Late last March, Jack Lawson, a research scientist with the province’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, received an ominous cellphone picture of four dark-grey lumps, like abandoned inner tubes, lodged in the ice; he feared they were the distended lungs of dead whales, and took a helicopter flight over the icy region to investigate.

The St. George’s waters have always been dangerous for marine mammals. In winter, the bay freezes over, making it uninhabitable to animals that rely on surface access for air. As the temperature warms in spring, ice sheets break off and are blown westward, creating a pathway through which whales can swim into the bay—but a strong wind from the opposite direction can send the ice back, effectively sealing the trap. In shallow waters, whales are crushed between incoming ice and the sea floor; in deeper waters, they drown.

The trap once killed four blue whales in a single year, a sizable loss, given that there are only 250 adults in the northwest Atlantic region. The species is still recovering from the effects of industrial whaling—a practice that peaked in the ’20s and ’30s—and the regional population isn’t regenerating fast enough. “We rarely see calves in the northwest,” says Lawson. “They just don’t seem to be breeding, and we don’t know why.”

What Lawson saw from the air was even more horrifying than he’d expected: not four, but nine blue whale corpses—the most extreme die-off ever recorded in a single season. But even this might have gone underreported, had it not been for what happened next: three blue whale carcasses, each more than 20 meters long, washed up on the Newfoundland shore, one of them near the 700-person fishing village of Trout River. Residents were terrified. “If that whale does explode,” town clerk Emily Butler told the St. John’s Telegram, “we don’t know what danger that would be to our infrastructure…or to people.” A website called “Has the Whale Exploded Yet?” got millions of page views, and stories about the volatile carcass made headlines around the world.

The panic over exploding whales originates not from biological reality, but mostly from a video, circulated online, of a 1970s newscast in which Oregon highway officials attempt to dispose of a sperm whale carcass with a half ton of dynamite. The results: hapless sightseers caught in a meteor shower of whale flesh, a few dented vehicles, and one of the most popular Internet videos of the pre-YouTube era. Since then, exploding whale footage has become a genre in its own right: whale guts befouling the streets of Tainan City, Taiwan; a researcher in the Faroe Islands caught in a mess of blubber. In both cases, human meddling probably triggered the “explosions”—which are better described as minor blowouts of decomposition gasses. (The animal carcasses remained mostly intact.)

The results: hapless sightseers caught in a meteor shower of whale flesh, a few dented vehicles, and one of the most popular Internet videos of the pre-YouTube era.

There were no spontaneous combustions in Newfoundland this year, but the threat of flying guts symbolizes a more troubling reality: something awful is happening to blue whales in the northwest Atlantic. It’s possible that climate change contributed to extreme freeze-thaw cycles, luring more whales into the trap and then turning on them severely; ocean contaminants in the region could also be making them sterile. What’s certain, though, is that this year’s die off was a devastating blow to a tiny, imperiled community—one whose survival is oddly bound up with our own anxieties.

Whales are icons of human vulnerability—totemic canaries in our ecological coal mine. They die unexpectedly. They wash up on shore seething with toxins. And they explode—if not in reality, then at least in our frightened imaginations.

*

The Trout River crisis was another chapter in the history of our bizarre fascination with whales, a tradition rooted in rumour, myth, pseudoscience, and narcissism. It’s easy to understand why whales are so compelling. They are beautiful and repulsive, otherworldly but oddly similar to us. Like mermaids and centaurs, they’re betwixt and between: you might describe them as fish without scales or mammals without feet. The Book of Leviticus counted whales as one of several abominations under God, and theologians in the Middle Ages took the existence of unshapely, deep-dwelling leviathans as final proof that Satan was real. (Get close enough to smell a rotting whale carcass, and you’ll probably agree.) Whales mean many things to different people, but at the centre of our whale fixation is the fraught, shifting relationship between humans and the non-human world.

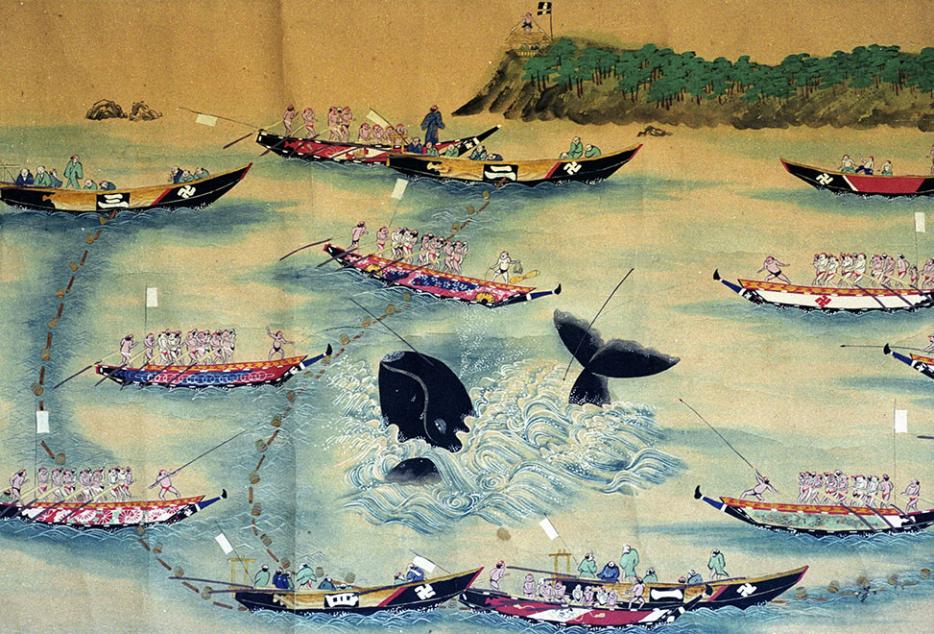

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, whales became unlikely icons for U.S. expansionism. This was the era of big game hunters, Bill Cody and Teddy Roosevelt, a time when rugged adventurists and presidential candidates would prove their mettle by roughing it on the frontier. According to historians Dan Bouk and D. Graham Burnett, whales “symbolized the unrivaled enterprise of Yankee seamen,” who went after “the ocean’s most feared and valuable prey in previously unhazarded waters.” Whaling boats were floating factories equipped to spend years at sea, and many cetaceans were harvested to the brink of extinction; the whale hunt became a potent symbol of human dominance over the planet’s most inhospitable regions. This macho seafaring culture spawned robust new industries. Slow-burning whale-oil lanterns lit up New England homes, and the baleen plates from bowhead and right whales were perfect for lining corsets, thanks to their subtle elasticity.

For taxidermists and collectors, however, whale bodies were elusive trophies. Unlike the hoofed animals of the Great Plains, which retain their shape for days after death, whales decompose quickly, their skin transforming into a layer of blubber. In 1907, a showman in Philadelphia was busted for exhibiting an imported whale that was actually just a wood-and-canvass dummy. The Smithsonian and the American Museum of Natural History eventually gave up on the dream of exhibiting an actual specimen and settled for plaster or papier-mâché replicas. Whales defied that fundamental 19th-century impulse to collect, preserve, and exhibit. In an era when taxidermy animals were an interior design staple, the whale body was an impossible—and therefore maddeningly alluring—trophy.

For taxidermists and collectors, however, whale bodies were elusive trophies. Unlike the hoofed animals of the Great Plains, which retain their shape for days after death, whales decompose quickly, their skin transforming into a layer of blubber.

If whales represented the triumphs and challenges of environmental conquest in Jacksonian and Postbellum America, they became something completely different in the era of the WWF. By the late 20th century, the extinction (or near-extinction) of once ubiquitous animals like the American bison and passenger pigeon had made hunting seem more brutal than brave. Silent Spring and A Sand County Almanac had become international bestsellers, and the language of conquest had given way to the theory of conservation.

Anthropologist Arne Kalland explains that, with the rise of the green movement, cetaceans became icons of environmental utopianism. They epitomized the complexity of the natural world: a realm that could teach us a thing or two, if we didn’t destroy it first. Whales were imagined as highly sensitive creatures swimming peacefully through rarified water. Many whale behaviours jibe with human notions of compassion: they sing to each other, nurture their infants into maturity, and care for their wounded and elderly. Given their longevity (they predate humanity by at least 25 million years) and brain size (larger than that of any other creature), it is possible to envision them as sage-like and profound—a species that has outgrown our territorial and violent impulses. Their ability to communicate across hundred-mile expanses seemed to indicate an otherworldly, near-telepathic sensitivity.

As Kalland makes clear, this eco-utopian “super whale” is actually a mash-up of different species-specific traits: the grey whale’s friendliness, the sperm whale’s braininess, and the humpback’s phenomenal ability to project sound across large ocean basins. In ecological terms, this hybrid creature is every bit as mythical as the unicorn.

Still, the whale became a powerful symbol that both helped and hindered the movement. Whales are fascinating and mediagenic—perfect for soliciting donations—but the sometimes single-minded obsession with their welfare diverted attention from more complex problems. The global whaling moratorium went into effect in 1982, making the practice increasingly marginal, but it was easier to demonize whale hunters—remote populations in Norway, Iceland, northern Canada, and Japan—than to condemn the industrial world for polluting the oceans. Unsurprisingly, whale utopianism had a xenophobic tinge. Kalland cites a Daily Star headline from 1991: “Greedy Japs gorge on a mountain of whale meat at sick fest.”

Some whales, like the humpback and blues, really do need our protections; other species, like the minke, could probably sustain a limited harvest. Of course, the thought of an intelligent mammal being brutalized with harpoons is obscene, but from a conservation perspective, there’s little to be gained from scapegoating small-time hunters for global problems. The super whale became the sacred cow of the green movement, and after the 1980s moratorium, many pods regenerated briskly; meanwhile, carbon emissions continued to rise.

*

The exploding whale is a new symbol, representing a new phase in ecological thought. Lawson insists that there’s no documented case of a whale spontaneously combusting. It’s true that the buildup of decomposition gasses can cause a whale body to bloat—prod the distended corpse with a blade, or strap it to a flatbed truck and drive it for hours across bumpy roads, and you may trigger a burst of noxious gasses and rotting flesh. (Both of these phenomena are documented on YouTube.) But steer clear of a whale body, and the results are unspectacular: it slowly deflates like a worn-out tire.

The exploding whale—like the elusive leviathans of the 19th century, or the eco-utopian super whale—is more imaginary than real, but it’s also a perfect analogy for our fraught ecological moment. In the last decade, the environmental movement has become increasingly fearful and apocalyptic. In the ’80s and ’90s, we were told to love our planet. Today we’re told to invest in sea walls and hurricane infrastructure, because our planet sure doesn’t love us. Scientists no longer warn of a vague future threat; instead they talk about a point of no return, which by some estimations has already passed. Paul Kingsnorth, co-author of the eco-millenarian Dark Mountain Manifesto, summed up his worldview in a recent New York Times Magazine interview: “Whenever I hear the word ‘hope’ these days, I reach for my whiskey bottle.”

Free Willy imagines the possibility of humans and whales reaching an intuitive understanding; in Blackfish that dream seems absurdly naive.

Whale symbolism is changing to match these doomsday prophecies. In 2010, American researchers took samples from northern Atlantic sperm whales, revealing perilously high levels of heavy metals. “You could make a fairly tight argument to say that it is the single greatest health threat that has ever faced the human species,” said biologist and Ocean Alliance founder Roger Payne in an Associated Press interview. The whales themselves aren’t dangerous to humans, since must of us don’t eat their meat. But whatever toxins are harming them are surely affecting us too. The bodies of St. Lawrence belugas are sometimes treated as forms of hazardous waste.

The movie Free Willy (1993)—about a sensitive orca who bonds with an alienated teen—epitomized the old utopian vision. A better film for our times is last year’s documentary Blackfish, about Tilikum, a traumatized, mostly docile killer whale who occasionally lashes out by scalping, maiming, or drowning his SeaWorld trainers. Free Willy imagines the possibility of humans and whales reaching an intuitive understanding; in Blackfish that dream seems absurdly naive. “When you look into [an orca’s] eyes, you know somebody is home,” says John Jett, a former SeaWorld trainer and one of the film’s talking heads. But who is that somebody? A sociopath? A prisoner? A traumatized child? It’s hard to escape the feeling, however misguided, that these illusive creatures guard some awful truth.

Watch any of the exploding whale videos on YouTube, and you’ll be amazed at how monumental the beached animals are; the surrounding people, by comparison, seem irrelevant and petty. When the blubber starts to fly, you might feel sorry for the poor humans caught in the storm. More likely, you’ll feel that they had it coming.