The airport was overrun. Businessmen with briefcases jostled against refugees clutching dirty bundles. Fourteen-year-old Erick was wearing everything he owned. On his feet were a pair of car-tire flip-flops he had traded for a biscuit ration in a refugee camp. He was gripping the hand of his five-year-old niece, Sibella, as panicked crowds swirled around them and pressed up against the doors that opened out onto the tarmac.

Fear rose like water in Erick’s chest. It was March 1997, and the country of Zaire was in the middle of a civil war. Rebel soldiers were closing in on the city of Kisangani, where Erick, his two sisters, and his sister’s young children nervously waited at the airport among hundreds of others for a seat on the last flight to safety. As the Air Zaire jet taxied toward the terminal, Erick glanced around him and guessed correctly that there weren’t enough seats on the airplane for everyone.

“What if the plane fills up and we have to go back?” he asked his older sister, Claudine.

“There’s always enough room,” she replied calmly. “They count.”

Erick didn’t believe her. At this point he had already walked more than 1,000 kilometres through forests and swamp and the soles of two pairs of shoes. He had nourished himself on cassava leaves until his fingers turned green and the skin of his stomach sucked against his ribs. He had watched people die, perforated by bullets, whittled by starvation, hollowed by despair. For months he and his siblings had struggled to stay one step ahead of death. So when the airport doors opened and people began to swarm toward the waiting airplane, Erick’s sharpened survival instincts kicked in and he ran forward, dragging his niece by the hand.

*

This month Rwanda is observing, with sorrow, the 20th anniversary of the infamous 1994 genocide. On April 7 President Paul Kagame lit a memorial flame that will burn for 100 days in honour of hundreds of thousands of Tutsis murdered two decades ago. Anyone who’s seen Hotel Rwanda knows the basic storyline: members of the Hutu majority orchestrated the slaughter of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in the space of 100 days while the world stood by. What won’t be publicly acknowledged—at least not in Rwanda—is that this story is much muddier than a simple morality tale of Tutsi victims and Hutu perpetrators. One of its largely neglected chapters is a war of vengeance Paul Kagame’s largely Tutsi army waged against Hutu refugees in the vast and trackless forests of eastern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) two-and-a-half years after the Rwanda genocide. This was the violence Erick and his siblings were fleeing when they found themselves jostling for a seat on the last flight out of Kisangani.

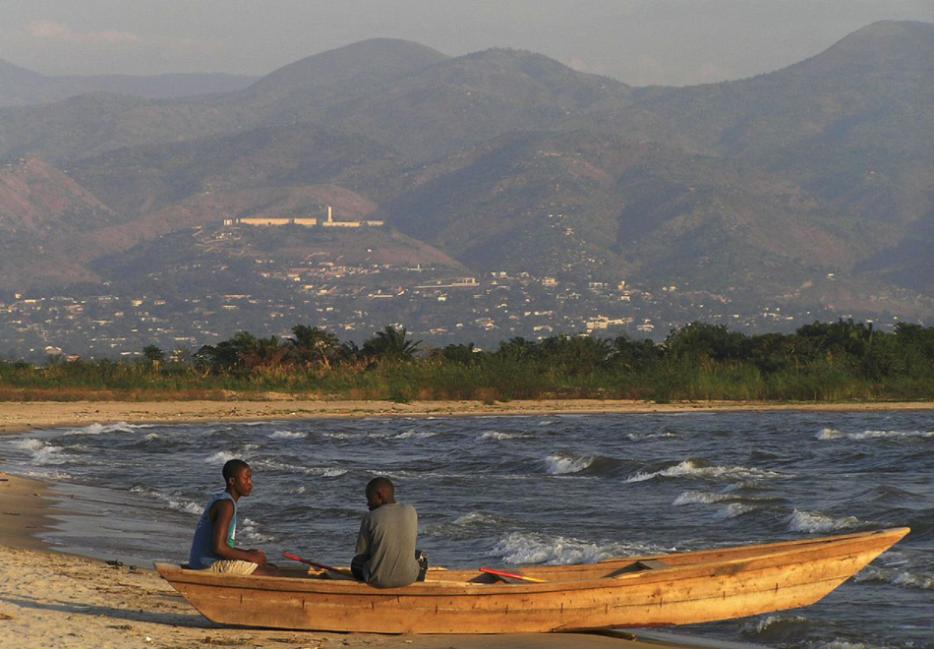

I first met Erick at a house party in Winnipeg. I liked him immediately—jocular, in his late 20s, with an expressive face that cracked easily into laughter. Surrounded by a group of listeners, Erick was relating colourful details from the life of his father, Aloïs Nzariragora, who fought for the Belgian colonial empire before his native Burundi gained independence. Erick’s father didn’t settle down and start a family until late in life. Erick described him—now in his 90s—as vital and stubborn. He still insisted on walking several kilometres each week to drink banana beer with his fellow veterans. Like his father, Erick struck me as an optimist, eager to seize whatever opportunities came his way. Erick was just finishing his nursing degree and making plans to marry his girlfriend, Stephanie, also a nurse. He spoke nostalgically about his childhood in Burundi—the curving beaches of Lake Tanganyika, the taste of tiny silver kapenta fish sautéed with hot pepper and onions. Like most people who arrive in Canada as refugees, Erick had lived through horrors. But he didn’t want that to define him.

“I don’t usually tell people those stories,” Erick said to me once. “It kind of makes it so people have to feel sorry for you. Me, I’m like, Suck it up! I just like people to see who I am and what I’m doing. It’s not about what I went through.”

It was only after we had been friends for several years that Erick recounted the details of his childhood ordeal. He and I were sitting in his upstairs study in Winnipeg, a couple of cold Heinekens between us, and a young-faced version of his father in uniform watching from a framed photo on the bookshelf.

Erick was born in Burundi, a small nation shaped like a human heart, located just south of Rwanda. The two nations are roughly the same size and have a similar ethnic make-up (about 85 percent Hutu and 14 percent Tutsi, with a tiny, marginalized caste called the Twa). From the air Burundi looks like a quilt sewn with every possible shade of green spread over pillows. Banana plantations and potato fields climb even the steepest slopes. Red dirt roads lace the greenery. Sunlight flashes on rectangular roofs of corrugated steel. In dry season a haze of dust veils the hills.

Burundi has its own history of genocide. Before the kingdoms of Burundi and Rwanda fell under the rule of German and Belgian imperial powers in the late 1800s, Burundi’s ethnic groups lived in a respectful, if unequal, hierarchy governed by an aristocratic class considered neither Hutu nor Tutsi. Burundi officially gained its independence from Belgian rule in 1962, and the years that followed were marked by a series of coups, assassinations, and violence between Hutu and Tutsi political parties struggling for control. Eventually the Tutsi minority gained the reins of power. Erick’s father lived through one of the worst genocides in the country’s history in 1972 when the Tutsi government tried to wipe out all the Hutu intellectuals. Aloïs, a Hutu, survived only because he agreed to the job of counting the bodies of his people as they were unloaded from blood-smeared trucks. He gave his children different last names from his own so their ethnicity couldn’t be easily traced. (For safety reasons, Erick asked that his last name be omitted from this story.)

When the genocide broke out in Rwanda in 1994, ethnic tensions in Burundi were also near boiling. Several months earlier, the assassination of Burundi’s Hutu president by Tutsi soldiers had sparked a series of killings against both Hutus and Tutsis. The violence in Rwanda aggravated the conflict further: Burundi’s Tutsi army began killing Hutus in the streets of Bujumbura, while armed Hutu militias sprang up to enact counter-killings against Tutsis.

At this point he had already walked more than 1,000 kilometres through forests and swamp and the soles of two pairs of shoes. He had nourished himself on cassava leaves until his fingers turned green and the skin of his stomach sucked against his ribs.

Erick was 12 years old, living with his family in a middle-class Hutu neighbourhood in Burundi’s capital, Bujumbura. He remembers those days of terror and confusion. “Everything was very complicated. You wake up in the morning and 200 people have died. There are bodies everywhere. The next day all the bodies are cleaned up like nothing ever happened. It’s very creepy. Your neighbour, whom you saw carrying a spear last night, comes up to you and says, ‘How are you doing?’ He’s all happy. He says, ‘Nice to see you. I’m sorry about what happened to your house.’”

One day Erick arrived home from school to find his own house a charred pile of rubble and his family missing. People were running in the streets gripping machetes. Terrified, Erick ran to another neighbourhood, this one still untouched by the violence. He spent the night hiding behind a stranger’s house. In the morning, the streets were littered with bodies. People abandoned their homes and headed for the Congo border. Erick, still wearing his school uniform and flip-flops, joined the stream of evacuees.

Erick’s older sister Claudine lived just inside Congo with her husband, a wealthy Burundian businessman and an organizer of the Hutu resistance. Claudine had heard about the massacre in her parents’ neighbourhood and was driving through the streets of Bujumbura in her Suzuki 4x4 with a chauffeur and a bodyguard when she found Erick walking with a crowd of refugees. She took him to her home. A few days later they found the rest of their family alive and well. Erick’s parents had hidden in a Catholic church and were now living in a refugee camp. They didn’t want to leave Bujumbura, where Aloïs had a job as a security guard, but they sent Erick and his younger sister Chantal to live with Claudine until things quieted down.

*

It was Paul Kagame who ended the 1994 genocide in Rwanda; to many, he remains a saviour. That year, he swept through Rwanda with his Tutsi-led army, routed the Hutu forces, and took control of the country. In the new government that formed, Kagame assumed the role of vice-president and head of the army. He became president in 2000, and has since built Rwanda into what’s judged to be among the continent’s success stories—politically stable, attractive for foreign aid, and with levels of economic growth that’s fostered advancements in education, health care, and women’s rights. Kagame surveys his city with an unflinching gaze from giant portraits that hang in offices and stores throughout Kigali. The streets are litter-free and petty crime is rare. Bono, Tony Blair, and Bill Clinton have praised his leadership. American universities grant him honorary degrees.

But four years ago, a story emerged that threatened this heroic image. In 2010, the United Nations published a 566-page report called a Mapping Exercise. The report, based on testimonies collected by a team of UN human rights workers, provides evidence of crimes against humanity committed in Congo between 1993 and 2003. The report’s most significant allegation was that Kagame’s troops carried out a campaign of vengeance against Hutu refugees in eastern Congo in 1996 and 1997. This war occurred almost completely out of sight of the rest of the world. Access to the region was difficult, foreign journalists and aid workers were barred from many areas, and international news media reported mainly on the civil war to overthrow Congo’s corrupt dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko. It wasn’t until a decade later, after the discovery of three mass graves in eastern Congo, that the UN embarked on a thorough investigation.

In 1994, when Kagame and his Tutsi-led army took control of Rwanda and routed the Hutu militias, two million Hutu refugees fled across the border into eastern Congo and settled in a series of UN-run refugee camps. Two-and-a-half years later Kagame sent his soldiers into Congo to break up the camps and root out the Hutu militias who were still causing trouble along Rwanda’s border. At the same time, Kagame was supporting a rebellion led by Congolese insurgent Laurent Kabila to overthrow Mobutu.

One day Erick arrived home from school to find his own house a charred pile of rubble and his family missing. People were running in the streets gripping machetes. Terrified, Erick ran to another neighbourhood, this one still untouched by the violence. He spent the night hiding behind a stranger’s house.

Witnesses later described to UN investigators how Rwandan soldiers and the Congolese rebels with whom they were allied raped, shot, burnt, or bludgeoned tens of thousands of Hutu men, women, and children in Congo. Kagame’s army reportedly blocked aid to camps of Hutu refugees and lured Hutu civilians to mass graves with the promise of repatriation. The systematic nature of the killings “cannot be attributed to the hazards of war or seen as equating to collateral damage,” the report states. “The majority of the victims were children, women, elderly people and the sick, who were often undernourished and posed no threat to the attacking forces.” Besides the tens of thousands of Hutu refugees who died violently, hundreds of thousands more perished from starvation, disease, and exhaustion. According to the report, these allegations, “if proven before a competent court, could be characterized as crimes of genocide.”

Kagame was furious when an early draft of the report was leaked to the press in August 2010. He called it “baseless” and “absurd,” and threatened to pull his troops from a UN peacekeeping mission to Darfur if the report was published. The UN released it anyway.

When Rwanda invaded Congo in November 1996, Erick was living with his sister Claudine and her husband in the town of Bukavu. Erick remembers hearing the thump of shells and seeing Congolese soldiers run past the house, throwing down their weapons and tearing off their uniforms so they could blend in with civilians. “Run,” the deserters warned. Claudine’s husband was away on a business trip. Erick, Chantal, Claudine, and Claudine’s three young children made hasty bundles of food, clothing, and cookware and joined the panicked crowds clogging the streets. They walked into the night, passing the smoking husks of exploded vehicles, until they reached the Gashusha refugee camp guarded by Congolese troops. The camp turned out to be a death trap. On their second day there, shells began falling among the gathered refugees. Erick saw whole families die. He remembers running, stepping over arms and heads separated from their bodies. His mind went numb.

Together Erick and his siblings fled into the vast mountainous forests of eastern Congo. This forest became their home for the next two months as they walked from one makeshift refugee encampment to the next. Often they received news that a camp they had stayed in had been razed by rebels only days or hours after they left it.

Each day they woke before dawn and shouldered their burdens. Fourteen-year-old Erick carried the family’s food—potatoes, cassava or whatever they could scavenge. For several weeks they had nothing to eat but cassava leaves boiled and ground to a bland paste that turned teeth and fingertips green. Thirteen-year-old Chantal carried the cooking pots, and Claudine carried her one-month-old son Chaka on her back. Claudine’s daughters, Sibella and Raissa, ages six and seven, each held someone’s hand and put one foot in front of the other for 10 hours a day.

“We dragged them,” Erick says. “If we had gone at their speed we would have been killed.” Sibella was the family’s alarm clock. Every morning she woke with a sob at 5 a.m.

The family wasn’t alone; they were part of an immense exodus of refugees walking on paths through the forest beaten by thousands who had already gone before them. The refugees were mainly Rwandan Hutus who had fled the refugee camps near the border when they were attacked. It was the rainy season. Days were drenched in rain and nights were smeared with mud. The fugitives slept in shelters built by hunters or makeshift tents left by other refugees. If you found a body in a tent, you dragged it out and took its place. Those who succumbed to injury, disease or starvation were left where they fell. There was no time to bury the dead or wait for the wounded. Erick remembers one woman who gave birth to twins during the flight. Unable to carry both, she picked up one child and left the other one swaddled in a cloth under a tree. “I still wonder what happened to that child,” he says.

The towns and encampments Erick names as he recounts his flight correspond with the sites of massacres documented in the Mapping Exercise: Bukavu, Goma, Masisi, Rutchuru, Walikale, Tingi-Tingi. A map on page 79 of the report shows a network of blood-coloured arrows originating along Congo’s eastern border and branching into the interior. The arrows mark the escape routes of fleeing Hutu refugees.

“In [the Walikale] region, massacres were staged on the basis of an almost identical plan designed to kill as many victims as possible,” says the Mapping Exercise. “Every time they spotted a large group of refugees, the AFDL/APR (Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo / Armée Patriotique Rwandaise) soldiers fired indiscriminately at them with heavy and light weapons. They would then promise to help the survivors return to Rwanda. After herding them up under a variety of pretexts, they most often killed them with hammers or hoes. Those who tried to escape were shot dead.”

But here again, Erick’s story resists a simple casting of villains and victims. Scattered among the fleeing refugees were armed Hutu militia members, many of whom had participated in the Rwanda massacres of 1994. These militants created a loose sense of order among those they traveled with and offered a measure of protection. Often they would hang back to skirmish with advancing rebel troops while the refugees fled. As a 14-year-old running for his life, Erick didn’t give much thought to his protectors’ possible crimes. “I was young. All I knew was that Tutsis wanted to kill me and these Hutus were protecting me. If those guys hadn’t been there, no one would have made it to Tingi-Tingi. We would have died right there. I have mixed feelings now, but I didn’t really care about the genocide in Rwanda at the time.”

For part of the journey, Erick himself carried an AK47 he’d salvaged from the refugee camp in Bukavu. He wore the weapon like clothing and slept with it next to his cheek. He’s fairly certain he never killed anyone with it, but on occasions he used the gun to bully people for food. Once, a skinny boy fired at the group of refugees. Erick and two other men shouldered their weapons and chased the boy through the bush. The boy led them to a hut where a Congolese family was just sitting down to bowls of hot food. Erick and his companions fired bursts into the air until the family fled, then devoured their food. “That was the best food I ever ate,” Erick says. He and his companions stuffed their sacks with supplies of dried meat they found in the hut.

Erick can still remember the feeling of power that pulsed though his 14-year-old arms every time he lifted his gun. “It was an adrenaline rush. There’s something about guns—once you have one in your hand you have no fear. It just makes you feel untouchable.” He doesn’t regret the decisions he made to survive. “I knew what I had to do to protect my family,” he says. “You do what you have to do, and you do what you think is right.”

*

In February 1997, after three months of walking, Erick and his siblings reached the Tingi-Tingi refugee camp where 150,000 Hutu refugees were living in rows of makeshift tents constructed from blue plastic tarps. Erick and his siblings were in a state of malnutrition and exhaustion. Their skin was stretched tight over their bones. Finally they could rest.

But not for long. In the camp, Erick listened to radio broadcasts reporting on the advance of rebel soldiers. The international press described it as a rebellion against Mobutu. There was no mention of the murder of thousands of Hutu refugees. When the rebels were 80 kilometres from Tingi-Tingi, Erick and his siblings decided it was time to get out. They walked seven hours to another camp for internally displaced Congolese refugees and lied about their nationality to get in.

There was no time to bury the dead or wait for the wounded. Erick remembers one woman who gave birth to twins during the flight. Unable to carry both, she picked up one child and left the other one swaddled in a cloth under a tree.

Only days later the Tingi-Tingi refugee camp was attacked. On the evening of February 28, Rwandan troops and Congolese rebels began shelling the camp. When the sun rose, soldiers entered the camp and used knives to butcher everyone still alive, according witness accounts in the Mapping Exercise. Several hundred fleeing refugees were trapped at a bridge across the Lubilinga River and gunned down. Hundreds more drowned or were crushed in the mayhem. It was one of the worst massacres documented.

News of the Tingi-Tingi slaughter spread panic throughout the refugee camp where Erick and his family were staying. The Congolese government sent a fleet of 10-tonne Mitsubishi trucks to transport refugees to the city of Kisangani 350 kilometres to the north. Erick and his family members managed to finagle a spot in the overcrowded vehicles. In Kisangani, Claudine was able to make radio contact with the members of her husband’s political party, now headquartered in Congo’s capital, Kinshasa. They sent her airplane tickets for the family to fly there.

A few days later, with rebel troops advancing on Kisangani, Erick and his sisters found themselves among the terrified masses thronging the airport. Erick forced his way to the front of the crowd trying to board the airplane. He and his family members managed to get seats on the plane as fistfights broke out among those left behind. When the doors closed and the airplane began to move, people were standing in the aisles. A flight attendant brought Erick something round and crisp and juicy. He had never seen an apple before. It was the sweetest thing he had ever tasted.

Erick and his siblings spent the next three years living as refugees in Congo and Zambia before their application for asylum was accepted by Canada. They arrived in Winnipeg in September 2000. When Erick contacted his parents by phone in Bujumbura, his father wept tears of joy. “If I die today, that will be okay,” he told Erick over the phone.

*

“Every human has the potential to be an animal,” Erick told me that day in his study in Winnipeg. “Those people who did those things in Burundi and Congo, they were human beings. They were our neighbours, people we used to share food and beer with.”

When Erick was in Grade 6 his best friend was a 14-year-old boy named Cadet. After school he and Cadet would sometimes dress up in a military uniform belonging to Cadet’s uncle and play soldier. Erick longed for the prestige and respect that came with a uniform. He hoped one day to join the military, just like his father.

One day Erick and Cadet were walking home from school when Cadet opened his backpack and showed Erick his treasures: a steel bayonet and a live hand grenade. Suddenly Erick was acutely conscious of the fact that Cadet was a Tutsi and he was a Hutu. “Oh, that’s so cool,” Erick said to Cadet, faking fascination. In reality, he felt sick. Cadet let him touch the cold edge of the bayonet, but not the grenade. As the two boys walked further, the path dipped through an area of low bushes between two neighbourhoods. Cadet stopped and pointed at a corpse half hidden in the tall grass. “You see that guy right there?” he said. “We killed him last night.”

Erick didn’t see Cadet again for nearly ten years. In 2003 Erick returned to Burundi to visit his parents. While he was there he looked up his childhood friend. He and Cadet shared a cold beer and talked about their lives. “Are you married?” Erick asked. “Do you have kids?” Erick hadn’t forgotten the day Cadet had bragged about killing a Hutu, but neither of them brought it up. “Sometimes bringing up the root cause can bring so much pain it’s hard to move forward,” Erick says. They finished their beer, said goodbye and went their separate ways.

Memories don’t keep Erick up at night. Neither does bitterness. He has both Hutus and Tutsis among his relatives and friends. But as the world commemorates the 20th anniversary of the Rwanda genocide, it’s the one-sided retelling of the Hutu-Tutsi story that frustrates him. “You have to recognize that Hutus and Tutsis died, and you have to remember them equally,” he says.

In Kagame’s Rwanda, such talk can earn one prison time or worse. Four years ago, Victoire Ingabire, a member of a Rwandan opposition party, returned to Rwanda after years of exile. She visited a memorial to fallen Tutsis and lamented that Hutu victims of war crimes were not memorialized as well. She was arrested, tried for “genocide ideology”—a crime in Rwanda—and sentenced to 15 years in prison. In January of this year, Patrick Karegeya, Rwanda’s former spy chief who recently claimed to have evidence of mass killings committed by Kagame, was found strangled in a South African hotel room.

When it comes to Kagame, Erick is careful with his words: “I think it’s good to be open and say what happened and then move on. Hutus and Tutsis were killed, but one side was witnessed and the other wasn’t. Kagame presents the story the way he wants it to be presented.”