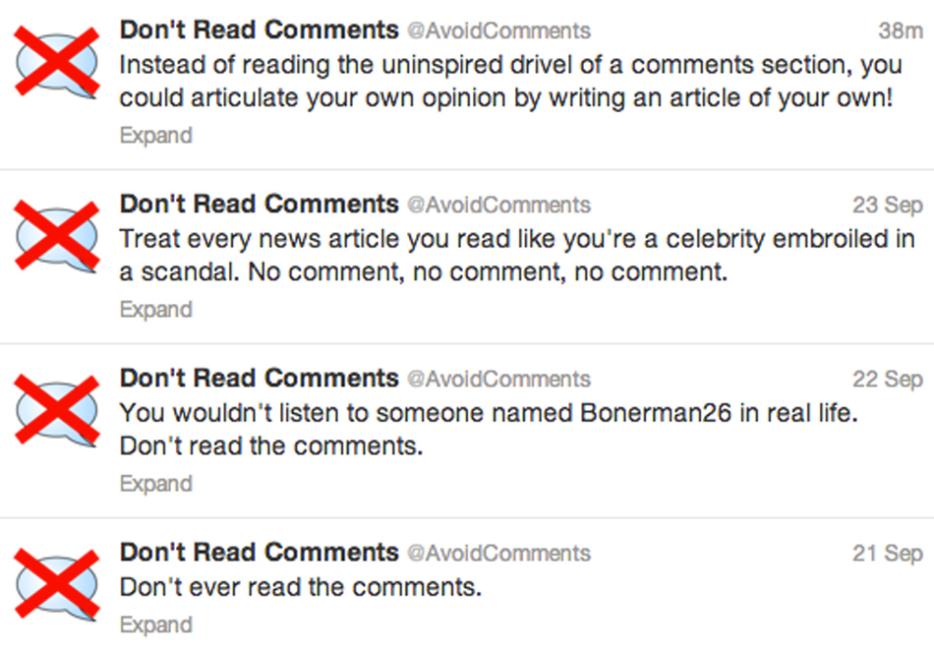

Don’t read the comments! So goes the ubiquitous online exhortation warning readers away from the bile in the boxes below, now so common that it has its own Twitter account.

If only that view weren’t so mistaken. Lost in the broad strokes of that puritan refrain is that the space under a news story or blog post can be awful or it can be brilliant, a seething mass of hate and idiocy or a veritable kaleidoscope of crackling ideas and debate. For me and fortunate others, the comment section has so often been the latter of those binaries—a place that feels more like home than chaos. In conflating the good and the bad, that pernicious phrase of “Don’t read the comments” erases this crucial aspect and more.

The story of the comments section is a relatively simple one. It’s laid out well in this excellent recent New York Times piece, which points to the way the comments section started as a good idea on less popular sites that then morphed into something terrible upon hitting the mainstream. To wit, the question is partly one of scale. Importantly, though, author Michael Erard suggests that it might be the shape and nature of online comments themselves—stuck at the bottom of the screen, amorphous and disorganized—that draws out the adversarial worst in people, attracting a certain kind of commentary, rather than simply being a reflection of “society.” That’s why Gawker, for example, is now moving to a model more akin to annotation than traditional commenting.

But for so many of us, comments sections aren’t problems looking to be solved. Instead, they are places recalled and entered into with great fondness, endless founts of wisdom and conversation in which the very best of the web as a medium is to be found.

Where are these mystical Edens? For the most part, they are on smaller sites, ones where the readership often grows from an author’s circle of friends to include a wider group. The familiarity sets a certain tone and builds a collegiality—comments that aren’t full of bile but, rather, encouragement and reflection.

For me, it started with the now-defunct Fimoculous, a link-blog about media and tech run by writer and entrepreneur Rex Sorgatz. Though each post was often just a sentence or two, cracking conversation would emerge, often between bright, literate people with their finger on the pulse. And instead of Paul Ford’s brilliant encapsulation of so much Internet discourse—“why wasn’t I consulted?”—the sentiment was frequently much more one of, “Yes! This is so cool, and here is what it makes me think…”

Encouraged by the engagement there from those I respected, I took to blogging myself. Slowly, commenters appeared, each new one accompanied by a thrill of recognition, followed by the pleasure of talking to interesting, diverse people about things I was interested in. Smart subtle threads about, say, aspiration and feminism, or dining alone, or the future of reading emerged, and as I started to recognize people liked what I had to say, it helped turn a hobby into a career.

It’s true that now social media is supposed to now house that kind of discourse. But the friends you dine with are not necessarily the same as those with whom you talk about the modern mediascape or architecture. Commenting communities gather around topics and ideas, not social bonds, and it’s a difference that neither Facebook nor Twitter can yet make up for.

It’s a reminder, too, that comments on newspaper sites or the Huffington Post are terrible not because they occur in a comment section, but because the audience is just too big and diffuse, utterly disconnected from the writer and their fellow squawkers. The admonishment/plea to not read the comments is a bit like standing in a Chapters and saying “Don’t read books” because, inevitably, many of them suck; it is the amorphous glut, not the character of the thing, that is the issue.

But beyond the erasure of distinction between good and bad, it’s also as arrogant as it is ignorant. Sure, comments are often filled with stupidity and vitriol, but only the most self-assured and oblivious could believe that authors or media organizations shouldn’t be challenged. Even at their worst, comments provide an alternate space for alternate readings, a locus for views you may not want to acknowledge, but exist. Yet, at their best, they are like a prism held to the light of the original piece, scattering and multiplying the colour and shade hidden in the source material.

Over the past year, about thirty other regular readers of a blog and I have been meeting online once a week to discuss ideas about media and tech. Next month, we’re going to meet up in Florida to discuss and crystallize the ideas we have been forming, a gathering that has largely come about because of the community developed in the boxes beneath the site’s posts.

You could say it’s a conference, or a seminar. But the way I—and I’m sure many others in the group—might best describe it is a comments thread come to life. That’s the association we make because, far from a “cesspool” or waste of time, a meeting of minds and the exchange of ideas is what we’ve come to think when it comes to that much-maligned Internet phenomenon. And if the only thing you ever think about the comments is the knee-jerk, misguided “Don’t read them!,” you are, quite simply, missing out.