I first encountered James Joyce’s Ulysses when I was a sixteen-year-old university freshman. I was starting pre-med, on my way, I thought, and others prayed, to medical school, after having jumped the track that would have led me to the priesthood. English Literature was a required course for all first year students—they could choose between Introduction to the Novel and Introduction to Poetry.

At that time, at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland, very few of the faculty were Newfoundlanders, and I had never heard of a novel written by a Newfoundlander. My professor was from Boston, possibly Harvard-educated, and definitely gay, or so the rumour went among the other students: in my world, gays were as rare as Newfoundland writers. I remember him as Professor Boston, so I’ll call him that.

For reasons that still elude me, he chose the following books for our introduction to the novel: Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Joyce’s Ulysses, Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo, William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury…well, I think you get the picture. These four would turn up on any list of most experimental, most “difficult” novels.

Professor Boston kicked off the course with Ulysses. Many of my fellow students were budding English majors who had chosen English on the advice of guidance counselors or parents who were convinced by the students’ sensitive high school responses to the lyrics of Simon and Garfunkel, To Kill A Mockingbird or Huckleberry Finn that they had literary gifts that, if shared with the world, would make it a better place.

I researched opinions of Ulysses. Saul Bellow said that Joyce was the “literary dictator of the twentieth century,” all style and no substance. Too severe, I thought, and probably owing to Bellow’s frustrated, ego-driven desire to be the literary dictator of the twentieth century. The British novelist Anthony Burgess, thought the book to be a complete fraud and claimed that Joyce’s true masterpiece was his last book, Finnegan’s Wake.

Three days into Professor Boston’s teaching of Ulysses, many frightened-looking, teary-eyed kids were wondering how to break the news to their parents that, by the standards of the university, they were illiterate. But they adapted quickly, defecting from English Literature into the arms of courses they had heard it was impossible to fail; sociology, anthropology, political science.

Six of us stayed in Professor Boston’s class, including the captain of the university’s Greco-Roman wrestling team, a blonde, black-leather-jacket-wearing Adonis with whom Professor Boston was so smitten that he carried on a semester-long in-class conversation with him, smiling and nodding encouragingly whenever the Greco-Roman made even the most oblique reference to any book—and ignoring the rest of us.

I gamely worked my way, unguided, through Ulysses, punctuating the unpunctuated passages, etc. I decided the world would be a better place if I was not among its doctors, and I dropped pre-med. Consulting the university calendar, I noted that Ulysses was not on the syllabus of any other English Lit courses, not even graduate courses, and that it would not be difficult to dodge Professor Boston on my way to an English degree.

A few years after graduation, while working as a newspaper reporter, I realized that I was essentially uneducated. I became an autodidact, prescribing for my self a Great Book reading binge that lasted five years. For five hours a day for five years, I read St. Augustine, Plato, Aristotle, Sophocles…Kant, Hegel, Schopenhauer…Freud, Jung. I read history, poetry. I read everything, and found nothing unreadable, not even St. Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologica.

Near the end of the binge, however, I was once again confronted with Ulysses. This time, as I made my way through it, I seemed to cross over a threshold into comprehension. I got it—not in the same way that the thousands of academics who fashioned careers for themselves explicating the text got it—but the way, I suspected, that Joyce hoped readers would get it.

I decided two things about the book. Leopold Bloom, one of the two main characters, was one of the greatest creations of literary comedy of all time. And the other main character, Stephen Dedalus, was not. Not by a long shot. Stephen reminded me of Professor Boston. He was a pompous, brooding, self-important boor whose supposedly massive intellect was nowhere apparent in the book that was therefore, I decided, deeply flawed. What a sense of relief, release, emancipation I felt. The book that many thought of as The Book was just a book. It was still great because of Bloom, though, whom I thought was on a par with Don Quixote, Falstaff, others.

I researched opinions of Ulysses. Saul Bellow said that Joyce was the “literary dictator of the twentieth century,” all style and no substance. Too severe, I thought, and probably owing to Bellow’s frustrated, ego-driven desire to be the literary dictator of the twentieth century. The British novelist and auto-didactic pan-intellectual, Anthony Burgess, thought the book to be a complete fraud and claimed that Joyce’s true masterpiece was his last book, Finnegan’s Wake. I dipped into Finnegan’s Wake and quickly decided that to read about it would be more fun that to read it. And reading about it confirmed my view of Ulysses. Joyce must himself have come to realize that his forte was not hyper-solemn artiste characters like Stephen, but ones like Bloom.

So back to Ulysses. There was Bloom, and the wonderful depictions of Dublin. The promise of Bloom’s return to the stage made Stephen’s soliloquys barely bearable. In spite of Stephen, I fell under the spell of the book. I vowed that I would one day do for St. John’s, Newfoundland, what Joyce had done for Dublin.

He, I decided, had to be a she. I had to turn Ulysses on its head. And so was born Penelope Joyce—Penelope, in Homer’s Odyssey, is true to her long-absent husband, repelling a succession of suitors until her hero-husband makes his way home. My Penelope would be a lesbian who, while the father of her child, Percy, was away—his name would be Jim Joyce—would carry on affairs as dictated by her heart and her need for a monthly mortgage subsidy.

I considered making “my” Ulysses my first novel. Just as Joyce had plundered Homer’s Odyssey, built his book on the structure of Homer’s epic poem, I would structure mine on Ulysses. I posed myself two questions: why do something so derivative? If you do it, how will you surgically extract Dedalus from your book? (If I seem too harsh about Dedalus, consult Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man, of which Dedalus is the main character. The book somehow succeeds in spite of him. Joyce has Stephen compose—in what the reader is meant to believe is a moment of great artistic inspiration—a villanelle that is so bad it’s hard to believe it’s not a parody of something. Stephen is an aspiring poet, as Joyce once was. But Joyce, for all his poetic prose, was a novelist, as Stephen should have been, and this was something Joyce did not realize until after he finished Ulysses.)

I put my Joycean homage aside and wrote novel after novel over a period of years that became two decades, all the while thinking through my “Joyce” book. About a year ago, I finally worked out how it could be done. Stephen would have to go, period. The soaring intellect who hovered over Dublin in search of his spiritual father, Bloom, would, like his mythical counterpart, Icarus, fly too close to the sun, his wings of wax would melt and he would fall flailing into the sea, never to be heard from again. Except that Stephen was frequently Joyce’s mouthpiece for some nice ideas and turns of phrase, and he was very well-educated—better drag him up on the shore and visit his still-proclaiming corpse from time to time. Also to be jettisoned were the pointless displays of technical virtuosity, the serial parodies of every period of English Literature, for example.

I needed a counterpart to Leopold Bloom in whom I could incorporate the best of Stephen, a sensual, pleasure-loving, big-hearted, generous comedian. He had to be low-born autodidact like me, like Bloom, like Burgess.

He, I decided, had to be a she. I had to turn Ulysses on its head. And so was born Penelope Joyce—Penelope, in Homer’s Odyssey, is true to her long-absent husband, repelling a succession of suitors until her hero-husband makes his way home. My Penelope would be a lesbian who, while the father of her child, Percy, was away—his name would be Jim Joyce—would carry on affairs as dictated by her heart and her need for a monthly mortgage subsidy.

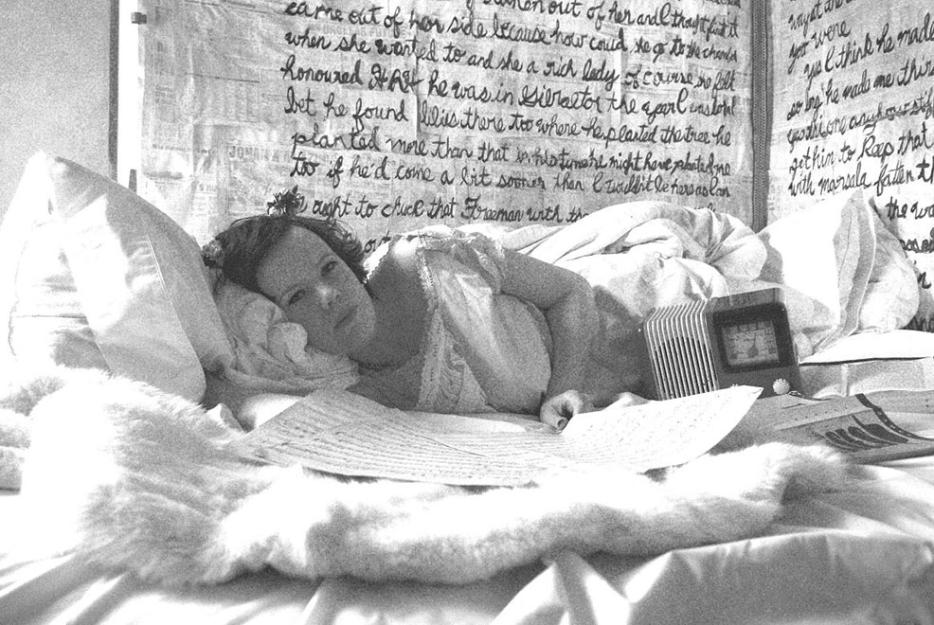

The characters of Ulysses would, in my book, morph into each other at my whim, à la Finnegan’s Wake. Penelope would sometimes be Leopold Bloom, sometimes his wife Molly Bloom, sometimes a self-taught intellectual. Her son, the physically flawed Percy Joyce, would be a more down to earth genius than Stephen Dedalus, and he would “search” throughout the book, not for his spiritual father, but for his flesh and blood, beautiful mother, whom he would fall in love with, and try unrelentingly to get into bed.

Ulysses takes place on June 16th, known world round as Bloomsday. Percy’s birthday would be June 24th, known Newfoundland-round as St. John’s Day. Because of his physical defect, Percy would be a social outcast, his a-sociality real, not a pose contrived out of haughtiness and spite like that of Stephen. But I would draw upon A Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man when I felt like it, using Stephen as Joyce did, as a mouthpiece for ideas that would otherwise have no means of gaining entry to the book.

And so I started it, the book I had thought about for twenty years—I finished it in eight months. I have tried, as succinctly as possible, to capture the “feel” of St. John’s. Percy, at the end of the book, stands in for Molly Bloom who pleasures herself for thirty pages via interior monologue at the end of Ulysses. The closing chapter of my book will probably not earn me an invitation to join The Knights of Columbus.

The Son of A Certain Woman. You don’t have to have read Joyce to “get” it. But it’s a touch more fun if you have.