I’ve been looking at Jessica Grant’s face for thirteen years.

She comes from the kind of small New Brunswick town where a lot of people have a little Native blood but nobody talks about it, and there’s something in Jess’ deep-set eyes and wide mouth that made post-colonial lit teachers look at her expectantly. She has a widow’s peak, and when I met her she was going prematurely grey at twenty. This year she started dyeing her hair, and it’s like she’s younger than I ever knew her.

The other day, I invited her over so I could draw her picture. When she came to my door, the first thing my brain did was flip through a million flash cards of all the faces I’ve ever seen before coming up with the match: Ahh, Jessie. I was rewarded with a flood of dopamine, the happiness chemical. As always, we hugged like one of us had just returned from war. My neurons fired celebratory rockets to fête her arrival.

In The Age of Insight: the Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain from Vienna 1900 to the Present, Nobel Prize-winning scientist Eric R. Kandel examines how we find meaning in the faces of others, through the confluence of neuroscience, biology, psychology, and portraiture. His exploration centres on Vienna in 1900, where the salon culture encouraged an easy intermingling of scientists and artists. Around that time, the discovery of the X-ray made it possible to look literally inside another person, and Freud’s popular new theory of the unconscious opened another window onto what unspoken and perhaps unspeakable things we might find there. All of this led to a new kind of portraiture: portraits not of the outer, but of the inner self.

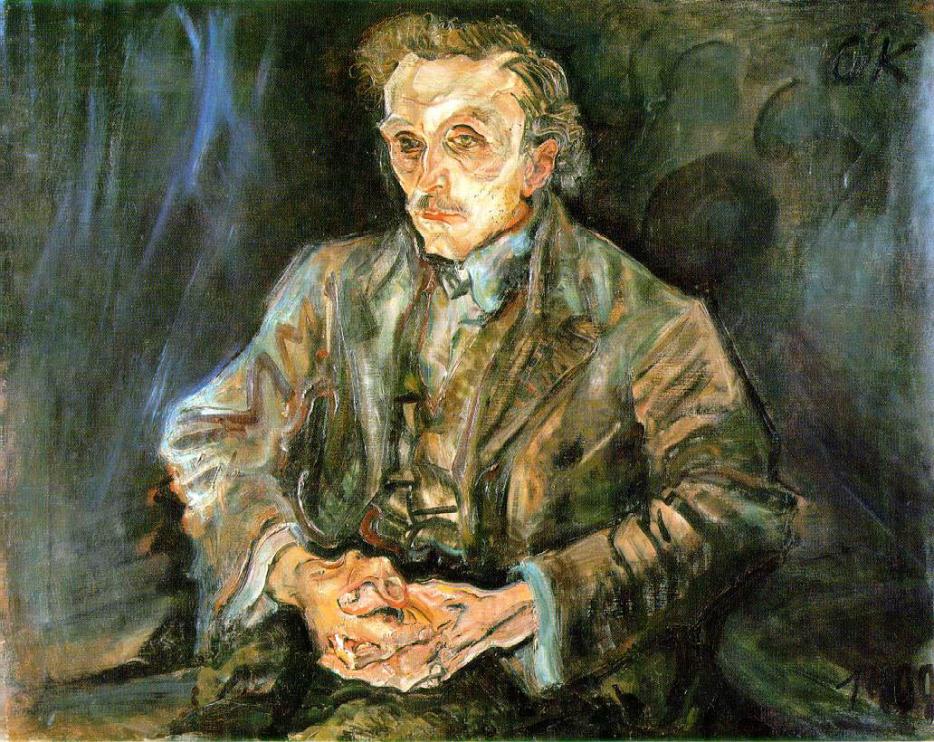

Oscar Kokoschka was one of the first painters in Vienna to try to use the face as a portal to the mind. He seems to have seen himself as a sort of psychological can-opener: “What used to shock people with my portraits was that I tried to intuit from the face and from its play of expressions, and from gestures, the truth about a particular person.” Kandel calls him “the first Austrian Expressionist,” and his idea that depictions of the face could be used to show the sitter’s mental state was so new and frightening that he “burst upon the Viennese art scene like a werewolf in a garden.”

I sat Jess down at one end of the table in my kitchen with her back to my shelves of plates and cups, and shone my standing lamp on her right side. The wall behind her was turquoise, and she was wearing a yellow sweater and holding a long-stemmed glass of red wine. She leaned her elbows on the table. Kokoschka encouraged people to talk or eat or otherwise engage themselves while he painted them, so I said to Jess, “Just talk to me like normal while I draw you.”

Contemporary psychology agrees with Kokoschka’s idea that everything you need to know about a person’s mental state is subtly coded onto his or her face. In the 1970s, psychologists Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen began a taxonomy of facial expressions, recording all the tiny movements of facial muscles that expressed what they considered the six universal emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. In the 1990s, Ekman added amusement, contempt, contentment, embarrassment, excitement, guilt, pride in achievement, relief, satisfaction, sensory pleasure, and shame. Ekman’s guide to recognizing these facial expressions has been widely applied in lie detection and law enforcement as well as in helping people with autism spectrum disorders learn to recognize the emotions of others.

While I tried to capture how her thick hair springs from her forehead in that jubilant way I’ve always admired, Jess told me about a character she’s working on who’s a semi-dominatrix—Jess is a comedy improviser, and she’s recently started staging one-woman performances. “She gets turned on by the whip she’s carrying and I’ll put it in my mouth, but then because it’s made of this cheap-ass fake leather the dye comes off on my face—it’s probably not safe, I should really treat it with something,” she said. “A great effect, though,” I said, and she said, “I know, that’s why I don’t fix it.” When I look at Jess’ face, I’m sure I would know she’s an actor even if I didn’t know her. All her features seem more pronounced than an ordinary person’s features, and as she talks her face rearranges itself with startling mobility. Just sitting at a table, she buzzes like a lightbulb.

It seems to me, though, that while someone’s feelings may be written on her face, our ability to decode that face—a cognitive process that preoccupies neuroscientists and art historians alike—is both highly sophisticated and miserably unreliable. Of the thirteen years that Jess and I have been friends, I’ve probably spent twelve of them trying to figure out what she’s thinking. We were roommates in our paranoid, self-hating early twenties, and (along with another friend who practically lived with us) we developed a morning ritual question: “Jessica, are you mad at me? Good, I’m not mad at you either. Matthew, are you mad at me? Good, me neither.” Kandel writes that one of the reasons why the Mona Lisa is such an arresting painting is the famous ambiguity of the face—is she happy? Is she sad? We’re caught between interpretations. We have to look again; and again.

When I show Jess my drawings, they look like this: a Gorg from Fraggle Rock; a tarantula; a mask of evil; and the best one, of which I tell her, “This is kind of what I picture Gertrude Stein looking like.” The face in the drawing has a strong chin, and hooded eyes, and a firm set to the mouth that I associate with a strong will and an independent mind. I say to Jess, “I mean, I don’t know, I’ve never actually seen her picture. But you know what I mean?” As she examines the page, I watch her face for flickers of discontent. I haven’t made the drawings pretty, with the small nose and symmetrical spacing that Kandel reminds me are the accepted hallmarks of feminine beauty. She laughs. “It kind of looks like me,” she says, “around the eyes, right? And the chin. You got something there, for sure.” I hope she’s not mad, but as hard as I look at her face, I can’t read her mind.