It may surprise you to learn that the National Book Critics’ Circle award ceremony, which took place last night in New York, was pretty sparsely attended. It was not black tie, it was not a red carpet, and even the Powerpoint presentation which accompanied it was dominated by a minimalist aesthetic. And really, of course, no one expects the Oscars: books simply don’t occasion the same glitz. But the auditorium at the New School was perhaps half full.

It’s hard to resist extending that into a metaphor about how unpopular critics can be, even in the community they serve. Yet awards remind you that when artists complain about critics they mean “the people who don’t like my art.” Rare is the person with the fortitude to turn down an accolade, even when it comes from the hated critics. And in America, the NBCC awards occupy a space somewhere between the Pulitzer and the (much-debated) National Book Award, i.e.: they’re one of the more coveted prizes. (Full disclosure: I am a member, albeit a recent member, of the NBCC.)

The sad truth is that most of the missing attendees, who included a good two-thirds of the award winners, simply don’t do the kind of work that pays the kind of money it costs to live in, or travel to, New York. That’s why the space looks like it needs seat-fillers, because the resources connected with “serious writing” in America are quite limited. The President of the NBCC, in fact, quite apologizes for even charging money for the post-ceremony reception, noting that it’s the only time the NBCC does so.

The slightly humble tone continued with one of the evening’s early honorees: the critic William Deresiewicz, who accepted the NBCC’s general prize for achievement in criticism. He rather pointedly admitted that critics always imagine themselves under siege, somehow. And then he quoted aesthetic justifications for the practice of criticism—allowing all of us to share in our experiences of art, that sort of thing—before coming to the real point: the woeful economics of engaging in it. Remarking on the fact that his prize would come with $1000 for the first time in its history, Deresiewicz wryly added that, “I’m a freelancer, so I’ll expect the check in three to six months.”

It’s funny to watch because in Canada, our literary awards are so institutional, such definitionally big events, with their medals and ceremonies of state and big cash prizes. Even a prize like the Giller gets a red carpet and photographers. When people complain about a lack of funding it’s directed primarily at the government. There’s plenty to decry about how small the scene is, but there’s something entirely heartening about how seriously Canadians still invest money in their books. And about how much more stable, financially, the entire literary enterprise feels, while I realize that actual writers in Canada will tell you it’s something else again to live that life.

In America, by contrast, the world of serious literature’s material peril is a theme of every awards ceremony. Last year, when the Pulitzer prize was not awarded for fiction, due to what was by all reports a simple impasse between members of the Pulitzer Board over the choices suggested by the jury, everyone here flipped their lids. But they weren’t angered so much because they felt one book or another deserved the recognition. The concern was over the level of sales.

Still, it’s true that many fewer Americans will buy a book simply on the strength of the NBCC’s recommendation, which gives it a flexibility that the Pulitzer lacks. Including one to recognize that literature in English is produced in places other than America. By now you likely know that a Canadian won the Autobiography prize—Leanne Shapton, for her Swimming Studies, which I have not read. She, having just given birth, did not make an appearance at the ceremonies. And Marina Werner, a Brit, won the prize for criticism for her Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights. Among the nominees, even, was a French novel in English translation: HHhH. It didn’t win, though; the fiction prize went, for once, to the stereotype some insist is the picture of the Great American Novelist: a white man. The funny thing is that it was the first time such a person had won the fiction prize since 2005, when E.L. Doctorow took it home for The March. In between, the NBCC’s choices have spanned the galaxy: women, and people of colour, and women of colour, and this has been true going all the way back to 1975, when the first prizes were awarded.

The desire to do things a little differently in the critical community came up in the Nonfiction category too. Andrew Solomon’s winning Far From the Tree is all about how we value and deal with people who are different from us, though it examines it mostly in the context of parenting, and when, while accepting the award (“unfashionably,” as he put it, he was one of the two authors who actually showed up), he noted that he was proud to do so on the day the Obama Administration had announced its opposition to Proposition 8, in California, which sought to ban gay marriage.

And: earlier in the evening a lifetime achievement award had been given to Susan Gubar and Sandra M. Gilbert, the joint authors of The Madwoman in the Attic. Both academics, they’d devoted themselves to unearthing forgotten female writers, the kind of work that became a hallmark of feminist literary criticism. As the presenter noted, work like Gubar and Gilbert’s was responsible for giving us back works like Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, now widely assigned on syllabi. But in the larger world, that kind of thing is now treated as a hilarious throwback, sort of an adorable reminder of what the 1970s were like. As Gilbert recounted, when the two were in the midst of the work their male colleagues were often skeptical. Her husband, she said, came to classify their objections into two categories: “My wife doesn’t feel that way” and “Men suffer too.” Everyone in the audience chuckled heartily at this. But outside the NBCC world, those objections still exist.

--

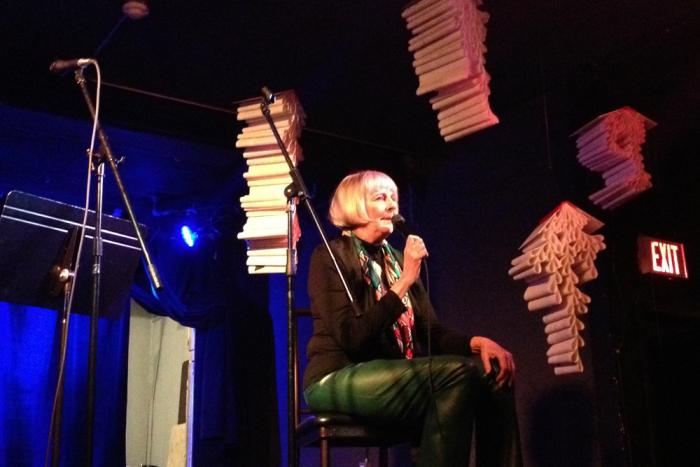

Andrew Solomon won the National Book Critics’ Circle award for general nonfiction, photo by Annie Leibovitz