“It’s a great pleasure to tell the truth of the world to children, and have their minds blown open,” Patsy Aldana beamed from the stage. The former publisher of Groundwood books was presented with the Writers’ Union of Canada Freedom to Read Award last night, at an event meant to celebrate the efforts of the Book and Periodical Council’s Freedom to Read Week. “The biggest issue we are facing in our freedom to read,” Aldana continued, “is the diminishing capacity of publishing in this country; we need to really fight to keep our network of stores, our network of publishers, and our network of readers vital.” There was a huge round of applause.

In its 29th year, the Freedom of Expression committee has partnered with Raconteurs, a local storytelling event produced by Alicia Merchant and Laura Louise Tobin. Every month Raconteurs puts on a show of live and true storytelling, and every month it’s totally sold out. “When I moved to Toronto in 2010, it was the first event I went to,” said Erin Stropes, a member of the FOE committee and the person who came up with the idea for the collaboration. “The people who would be interested in this, in promoting freedom of expression, they’re mostly young and very engaged. Essentially, they’re the Raconteurs crowd.”

Once the award was given, the storytellers took to the stage. Steph Guthrie, a local feminist activist and organizer, started us off with a story about receiving threats from misogynists on the internet after she used Twitter to start a discussion about accountability and violence. She’d spoken out about a man who had developed a computer game that glorified violence against women, and she kept coming up against men who told her that, by exercising her right to speak out against the game, she was impeding their freedom of speech. “Freedom of speech does not mean freedom from criticism,” she reminded the audience. It was a nuanced position, and brought a welcome sense of ambiguity to the issues at hand.

Guthrie was followed by Bruce Walsh, who, in an excerpt from a talk he’d given at a TEDx event, described how learning about the Holocaust as a young gay teen saved him from suicide. “If Germany was wrong about the Jews,” he recalled thinking back then, “then maybe society was wrong about me.” He developed an intense fascination with histories and literatures of the tragedies of Nazi Germany, discovering that the Nazis had also killed men out of hatred for homosexuality; and he made the poignant observation that Hitler began by burning books.

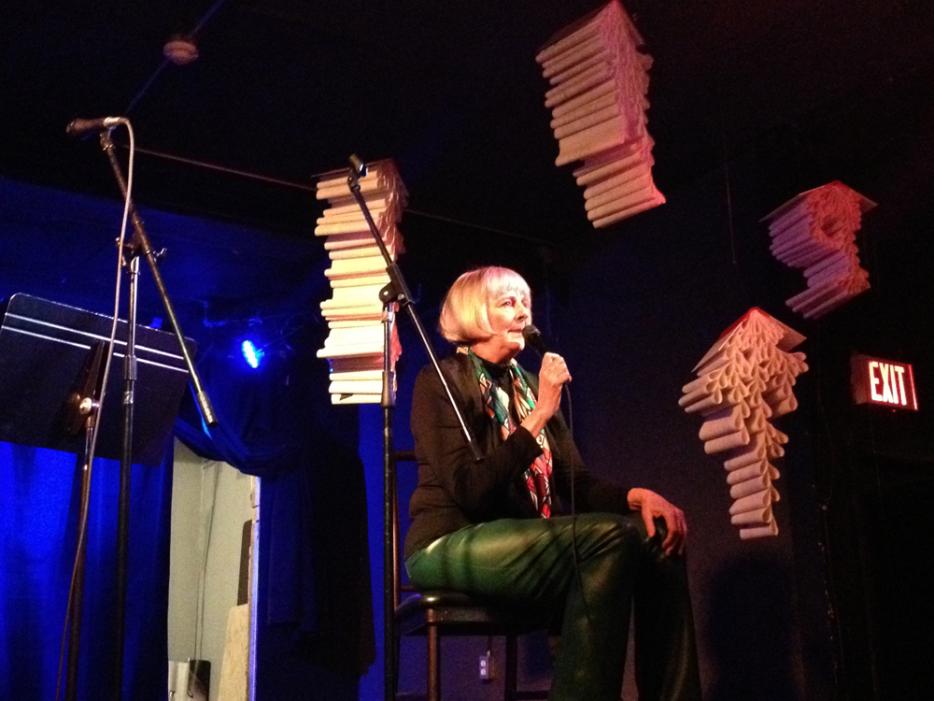

Susan Swan told a story about her first novel, The Biggest Modern Woman of the World, a fiction about the real-life Anna Swan: a 7’5’’, 400-lb woman born in Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia in the mid 1800s. Susan Swan, who has been 6’2’’ since she was 12 years old, described Anna as a possible distant relative, and told us about the anger she encountered when she gave a reading in Nova Scotia: some of Anna’s not-quite-as-distant relatives took umbrage with a scene in which their great aunt loses her virginity to a dwarf wielding an icicle. Swan tried to start a conversation with them, about how her novel was intended to honour their ancestor. But she began to realize that in a rural, oral culture, these young women felt a much closer kinship with Anna, and they were unable to see how fiction could have its own truth when it involved someone they loved. The story, Swan told us, doesn’t really have an ending—the Tatamagouche gift shop refuses to carry the novel, and so the book is unavailable in Anna Swan’s home town.

After a brief intermission, the audience filed back in for stories from Lisa Charelyboy, who writes about pop culture with a First Nation’s perspective; Catherine Frid, who wrote the controversial play Homegrown, about her friendship with Shareef Abdelhaleem, a Canadian Muslim and suspected domestic terrorist; and Ken Setterington, a writer, librarian, and wickedly funny story teller. Setterington said that his service in the library has taught him how easy it is for books to be unofficially challenged from within—he remembers how The Joy of Lesbian Sex sat for years in the cataloguing department, simply because none of the women working there wanted to have it on their desks.

He bookended his story with a memory from childhood: at summer camp, a boy who would become a famous Canadian writer brought an erotic paperback, which he read aloud to a tent full of boys. Setterington remembered him reading the words: “She raked his back with her nails and screamed in organism.” Someone yelled, “Orgasm, you moron!”—alerting a camp counsellor to what was going on. It’s Setterington’s first memory of having reading material taken away from him, and he wondered about the effect of that moment, or maybe that particular book: “Of the eight horny little boys in that tent, two of them grew up to be writers.”

--

Photo of Susan Swan, take by Emily. M. Keeler