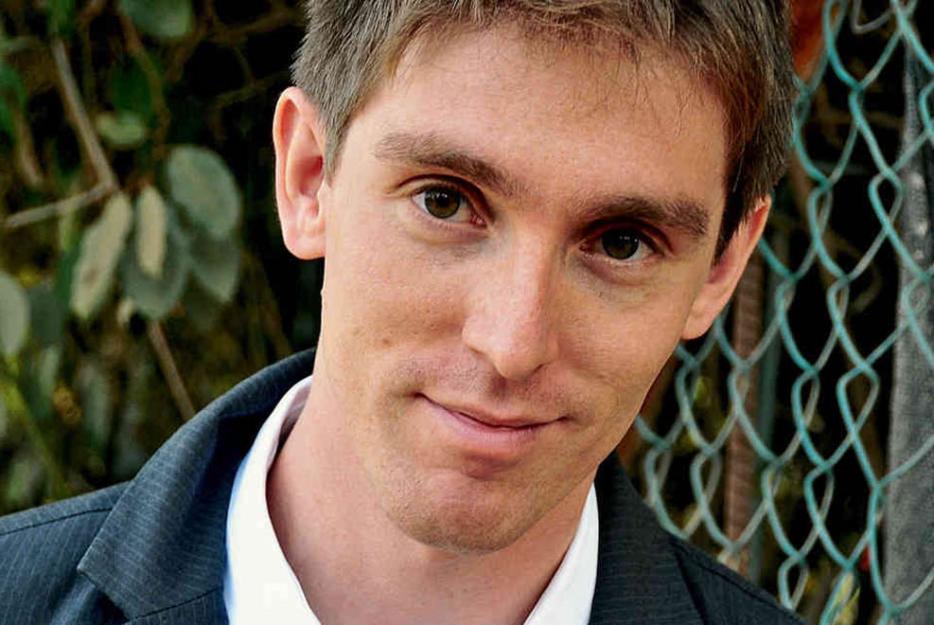

Avi Steinberg’s Running the Books is a surprisingly tender account of prison life, in which pimps nurture literary ambitions and inmates get into heated conversations about Shakespeare. It’s not your usual prison memoir as Steinberg was never incarcerated—his account is of the time he spent at Boston’s South Bay House of Correction teaching creative writing workshops and running the prison’s library. Warm and witty, he paints a complicated yet disarming portrait of life in the institution as witnessed by a person who was only ever halfway inside.

One thing that really jumps out in Running the Books is how the inmates developed their own kinds of written forms—I’m thinking about the skywriting and kites. 11“Kites” is prison slang for letters—the library functioning as a sort of contraband post office, where inmates communicate with each other through notes left in books. “Skywriting” is an elaborate sign system that segregated men and women inmates use to converse with each other. At South Bay, a man standing in the prison yard might sign in the direction of the women’s facility, which has windows overlooking the yard. Do you think this need to have coded, contraband forms of communication influenced the work your incarcerated creative writing students were doing?

One clear way that kites/skywriting were linked to my creative writing classes was through letter writing, through the burning desire to write letters. Many people who came to my classes were eager to improve their skills at writing letters. Prison is a lot like the 19th century. Letter writing continues to thrive there. There is a particular urgency to writing in prison—a letter is the difference between having a relationship with a person on the outside or not. Writing is the relationship. Like those old Victorian letters, the prose itself is heated by this dynamic.

There are so many ways in which creative writing is suppressed in prison. So much of writing in prison is associated with sheer malice and with legal warfare (inmates and staff members are constantly writing grievances and incident reports). There is little free speech in prison and no private property. Your cell can be searched at any time and your writings can be confiscated. Anything you say can and will be used against you—that’s the literary culture of the place.

And suppression could come in other, less obvious forms. Many inmates had gone through addiction recovery programs that incorporate writing assignments into their regimens. Perhaps this kind of writing serves its therapeutic purpose but, from a literary perspective, it’s stifling. It trains people to tailor their stories to the tastes of recovery-think, and to strangle these stories with the homogeneous language of the program. After I saw the 10th consecutive essay that described how someone had “hit rock bottom” I realized that I would have to figure out how to get my students to write in their own voices.

So, there were many ways in which a potential writer was forced underground, and could only speak in various codes. I tried to get them to come out, to tell the stories that they actually wanted to tell in the words that they really used.

You point out how unfathomable shushing would be in the prison library context. You paint it as an incredibly and actively social place, especially compared to your high school life of studying dense religious texts in quiet solitude. Have these opposing experiences given you any insights into the tension between the private and public aspects inherent to writing—or reading?

My story wasn’t animated by reading per se, but by the way in which books create a physical space, a backdrop for real-life dramas. The library provided a wonderfully literal and rather convenient version of this: here was a place that was actually made out of books, in which people’s lives and reading lives and, in some cases, their writing lives too, were all organically mixed together. (Many people weren’t reading or writing in the library and yet this space, created by books, was essential to them, as well. This comes up a lot in my story.)

Writing about other people who are reading or writing is always difficult. These are very private, internal activities. Think of those ridiculous cinematic depictions of a writer composing furiously in his garret as a violin soundtrack crescendos, as if that describes what writing is really like. But because I spent a lot of time with the patrons of the prison library, day in and day out—I wasn’t just popping in there to teach a writing class or run a book group—I got to see a full picture, how a person’s writing or reading connected with who he was, what his conflicts were, what kind of decisions he was facing. It was the unique properties of this book-space that opened up this perspective to me.

Do you think that the average library could or should adopt any of the tactics you’ve learned?

Many have, out of necessity. Public libraries have realized that their strength, one of the most relevant services they provide, may not come in the form of books but rather in the space that these books create for people. Libraries of the future may be less about books and more about readers. Even if people can buy or borrow books in digital form, these people are still isolated from one another. In a brick-and-mortar library, people are given a place to meet or to be alone while in a group. This is more important than ever; if bookstores disappear, libraries might be the best hope for giving readers a physical home. A library, as a physical entity, is desperately necessary in a prison. It is also a necessary entity in our digitized world, which to our poor animal souls can feel as isolating as a prison. I think many libraries get that.

You mention how books functioned as their own form of communication—you and the library’s staff and patrons would try to make yourselves understand each other a bit better by pressing books onto each other. What were the books you were gladdest to have read thanks to these recommendations?

A lot of people in that prison had been personally affected by or involved in the Boston Irish mob’s reign of terror from the 70s through the 90s, the Whitey Bulger years. I was given a number of books on that subject—I remember in particular, Black Mass—which were fascinating to read and discuss with people who had a personal take on the events and people in those stories. I was also handed Michael Patrick MacDonald’s memoir, All Souls, which does an excellent job describing how people who grew up in Southie, South Boston, had this mad, loving attachment to their neighbourhood even though it was such a deeply screwed up place.

Many of books I got were weird conspiracy theory tracts, which made for some spicy reading and also helped me understand the attitudes of mass paranoia common among inmates.

There were times when I re-read an old story with new eyes. In my book, I describe re-reading The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B Du Bois, at the insistence of a young inmate. For a period of a few weeks, there was a craze among women inmates to read The Diary of Anne Frank. I must admit that I wasn’t much interested in reading this book, which I had been forced to read as a kid in my Jewish school. But it was really worth revisiting. The conversations of imprisoned women on Anne Frank were truly amazing. It was heartening to read this book, which comes with so much heavy baggage for me, and to be able see it anew through the fresh eyes of these readers.

One of the things that struck me most about Running the Books was how much—and how beautifully—you used humour. It allowed you to describe some serious, complicated stuff. Is there a link, you think, between how humour functions in literature and how it functioned in your experience working in a prison?

Oh yes, there absolutely is a link. I realized early on that the only accurate way to write about my prison library was through humour. The place was this odd mix of quirky people and extreme boredom punctuated by moments of mind-bending absurdity. When I think of the sounds of the prison library, laughter is a constant. There was a refrain among inmates and staff that “someone’s gotta make a movie about this place”—and the implication was always that this movie would be absolutely fucking hilarious.

At the same time, of course, prison is really about heartbreak and misery. So the humour in my account had to be the kind that takes sadness very seriously, the kind that would expand the story’s emotional range. I believe the daily grind of the place itself suggested the form that the humour might take in the writing: it was the kind of place in which, minute to minute and hour to hour, you found yourself laughing—but then walked away thinking, “God, that wasn’t funny at all.” In writing the book, I tried to recreate that strange effect: sentence to sentence, there’s a lot of humour. But, somehow, the story itself, the sum total of these funny sentences amounts to something else.