A few months ago, while emptying out some long-neglected moving boxes, I found an old business card of mine tucked away in a novel. Sure, I felt a twinge of nostalgia for the big box computer store I worked at in the late nineties. But as an avowed ‘digiphile’, I was also struck by the fact that, with ebooks, you rarely find within them these odd ephemera of your past—unless, I suppose, you have the habit of keeping notes into your iPad case.

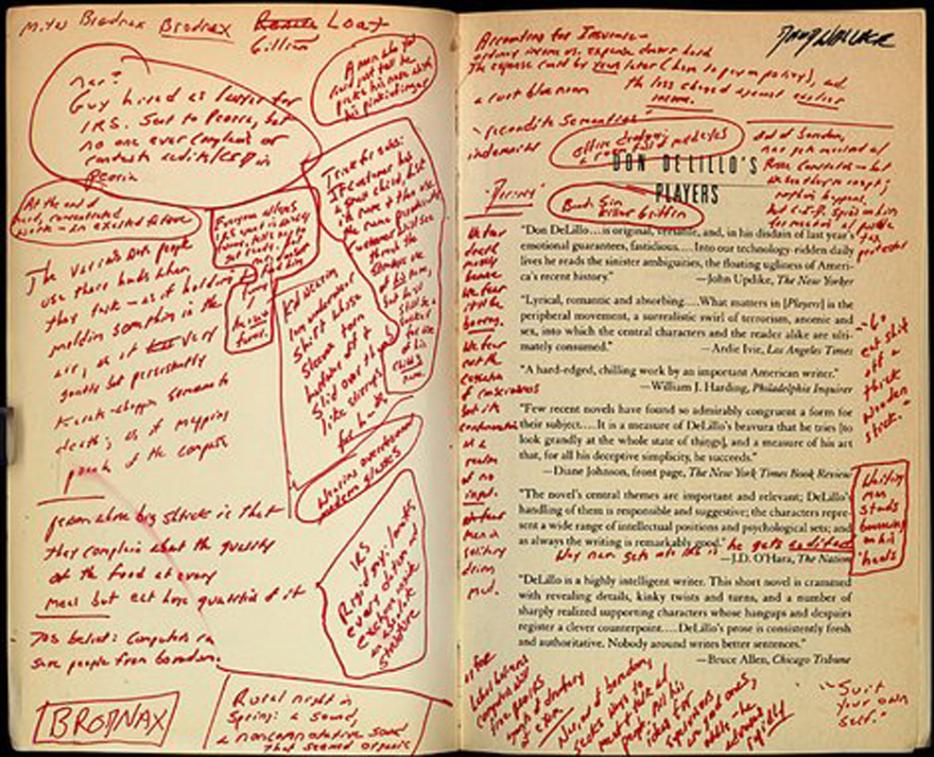

The sudden confrontation with who you used to be, though, seems even more intense when it comes to marginalia. While some consider it to be a sin, as someone who made the mistake of going to grad school, my books are littered with little fragments of notations, commentary and ideas. Sometimes these scribblings were just reactions, sometimes analysis of a persistent idea—but more often than not, they’d simply be signals for me to think more. “Hey!” the notes would often say “this totally links up to that other idea over there.” Sometimes I would and sometimes I wouldn’t, but it can be a fascinating thing to work your way backwards through what you used to believe.

The annotated book is one of the reasons print lovers have so ardently defended the form. As Sarah Werner, Program Director at Folger Shakespeare Library, recently pointed out, marginalia are a fundamental part of the book. Their use in early modern texts not only refutes the idea that the print book is static, and the ebook fluid, they also are a sign that new forms don’t simply replace old ones. The annotations that became part of print culture were an extension of the manuscripts that came before. The capacity to not only personalize, but extend and complicate a person’s relationship to a work through writing on what is already written is what can make dusty old books so great.

All that said, I think there’s something very cool waiting to be unlocked in the ‘margins’ of ebooks. Those notes I used as signposts for my thinking would be so much more useful to me if they were collected somehow, and maybe even organized. Like hyperlinks on web pages, if we could point to other ideas directly from the margins, the connections we could build between books and ideas might be pretty amazing. Maybe even more interesting is the idea of reading the aggregated marginalia of others as you read—though, perhaps on the second time through, so as not to taint the initial experience. Not only would it reshape how we read, it might also intriguingly and fruitfully invert the linear chain of reception we have now: that the book comes first, the reaction second.

It’s true that such possibilities exist now. With certain digital apps, you can read notes left by others, or see what sections they’ve highlighted. But it does feel that right now, it’s underutilized, I’d guess in part because for a lot of people, the book has become a kind of reprieve from the thoughts of many to focus on the thoughts of just two: a reader and an author.

I know some people don’t want what would amount to a literary Twitter feed in the margins of their books. But I do. One of the things that struck me most about Werner’s post on print and manuscripts is the idea of purposefully leaving space for something else to be said—of building into the very notion of the text that it is unfinished and needs readers to complete it. In a sense, what I am waiting for is a world in which the book is always double: always a mixture of both the body and margin. It feels like digital is the perfect place to make that happen, and to make it useful, and it is a phenomenon already part of literary history. For that, and many other reasons, I say bring on the electronic marginalia.

--

Image of the inside cover of David Foster Wallace's annotated copy of Don DeLillo's Players from the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin