When the Warriors took home the NBA championship on Tuesday, press promptly went into epic storytelling overdrive: it had been 40 years since the team’s last win, 33 since a rookie coach secured an NBA title, and all this while playing against LeBron James, an athlete who set his own finals records. What were the chances?

Well, according to basketball analytics, the chances were high, if not nearly certain. Yet, despite the statistical likelihood of a Warriors victory, watching these finals still involved all the stress and suspense of a narrative in which the ending remains a mystery.

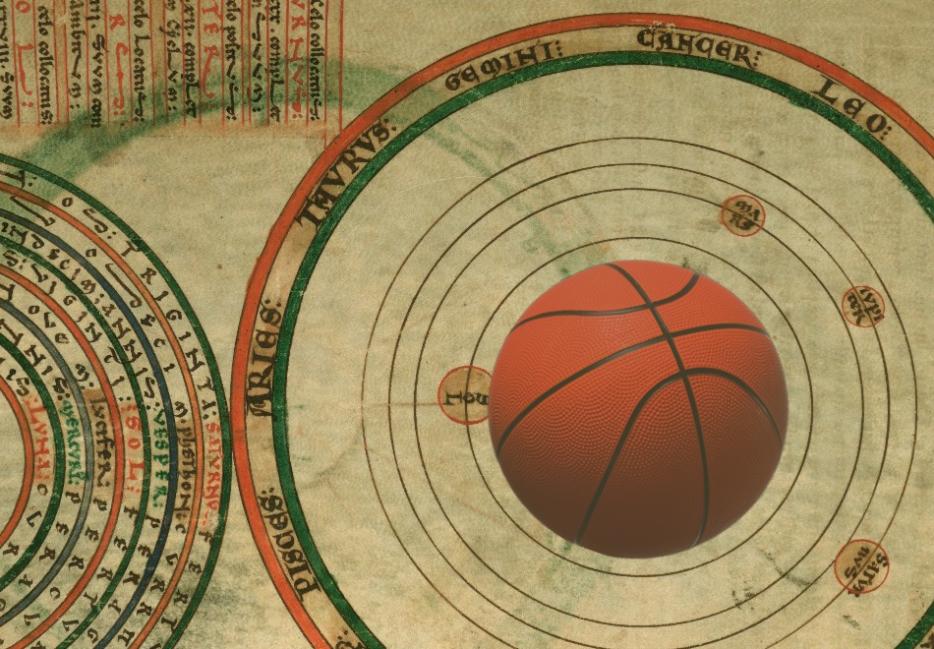

After game four, in which the Warriors came back in a big way, head coach Steve Kerr, explaining his team’s recovery against the then-leading Cavaliers, said: “There is karma in this game.” Kerr’s invocation of karma is not uncommon in talking about basketball. Rasheed Wallace coined the phrase “ball don’t lie”—a response to missed foul shots after questionable foul calls. But over the past decade, the rhetoric of statistics has, more and more, attempted to displace that of karma. The “basketball gods” that both writers and players so frequently refer to are now in slightly incommensurable dialogue with, well, math equations.

Often viewed as having been popularized by John Hollinger’s “player efficiency rating,” basketball analytics makes for—perhaps predictably—a lot of fetishized chart-making and sometimes-boring journalism. In 2006, economists David J. Berri, Martin Schmidt, and Stacey Brook co-authored The Wages of Wins—a stats-centered study that attempts, to quote Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker review of the book, “to solve the Iverson problem.” Why, in other words, did NBA’s Rookie of the Year (1997) and then M.V.P. (2001) Allen Iverson make the 76ers a better team by leaving it? In its conclusion, the authors emphasize that “without statistical analysis, one cannot see how the actions the players take on the court translate into wins. […] One can both play and watch basketball for a thousand years. If you do not systematically track what the players do, and then uncover the statistical relationship between these actions and wins, you will never know why teams win and why they lose.” Such a definitive claim on what is, in other words, sheer probability theory might sound naïve, but these days, every NBA team is sure to have an analytics department, and a large sector of basketball journalism engages directly with maneuvering statistics. And while there are certainly criticisms of mathematical modeling in the context of actual game play, such arguments aren’t nearly enough to deny the power of analytical reasoning.

One prominent critic of the rise of analytics—a term that, in replacing “statistics” or “data,” rings of self-legitimization—remains Charles Barkley, who famously dismissed the concept. “Analytics don’t work at all,” argued Barkley on TNT, “It’s just some crap some people who are really smart made up to try to get in the game because they had no talent.” He continues: “All these guys who run these organizations who talk about analytics, they have one thing in common. They’re a bunch of guys who ain’t never played the game, and they never got the girls in high school, and they just want to get in the game.” While Barkley’s dismissal of quantitative logic reveals his own investment in maintaining the aura around those who can actually play basketball, it also carries an implied critique about the racial and sexual biases underwriting analytics. That Barkley’s criticism is frequently characterized as a “rant” or “berserk” is certainly telling. Analytics is, in other words, a game that basketball players are not interested in playing.

But it seems, especially in watching these finals, that sports stats—perhaps predictably—can only hold so far. For instance, sports scientists have described LeBron’s performance as “unfathomable,” exceeding the criteria upon which analytics are based and exposing their limitations. “There may be no numbers that can do justice to how irreplaceable James has been for the Cavaliers in this series,” writes Neil Paine in FiveThirtyEight’s DataLab vertical. LeBron’s unfathomable plays are also exactly what makes watching basketball, and what made watching these particular playoffs, so exhilarating. The individualistic nature of basketball—that aspect of the game that makes it so deeply personality-driven—is also what troubles any attempts to apprehend it through systematic algorithms. As LeBron shows us, a single player can turn the trajectory of the game in explosive ways. When it comes to virtuosic basketball, mercury might always be in retrograde.

*

Mercuriality plays itself out most vividly in real time, and Twitter has been the best evidence of karma’s continuing influence on what we talk about when we talk about basketball. Twitter users responded to the Cavaliers’ Matthew Dellavedova’s particularly wild streak during games two and three of the finals by marveling at the magic at play. “Delly sold his soul to the devil,” stated Mike Loyko, an NFL draft analyst. Or, as an NBA writer put it: “So what do you think the devil is going to do with that soul Delly sold him?”

Hey Delly, have you ever danced with the Devil in the pale moonlight?

— Auntie Dee Dee (@SoCalGal64) June 15, 2015

Where's the devil and what's he doing with the soul Delly sold him?

— Nikko Ramos (@NikkoRMS) June 10, 2015

Dellavedova sold his soul to the devil

— Young Jedi (@JShamz_) June 10, 2015

My favorite explanation for Dellavedova comes from Grantland’s Jason Concepcion: “Delly is touched by god. Don’t question it. He looks like he’s about to dribble off his foot every second and throws up trash that goes in.” You don’t question magic. When Dellavedova’s zany moves on the court ceased to be so consistently effective in subsequent games, the devil was again to blame. “Dellavedova’s deal with the devil expired,” tweeted basketball writer Alex Wong, “He forgot to fax in an extension.” While citing Dellavedova’s relationship with the devil is far from earnest, the metaphor nonetheless demonstrates how writers and analysts alike resort to the language of superstition when describing the unexpected or, even, unquantifiable.

Greater than the devil are the basketball gods, who are frequently invoked in earnest—and sometimes almost in fear. After an embarrassing loss to the Cavaliers, Knicks President Phil Jackson tweeted about giving the basketball gods “heartburn.”

Each NBA game is an opportunity for players to show their "best" nature and please the basketball gods...and those who know what

"It"takes.

— Phil Jackson (@PhilJackson11) February 23, 2015

Today's game vs Cavs gave bb gods heartburn and those that know what "it" takes/means a smh.

— Phil Jackson (@PhilJackson11) February 23, 2015

Shortly after, Jackson tweeted again about the Knicks’ intention not to disappoint the gods again: “We will rebuild a team that fits together-guys that want to compete and play the way bball gods approve.” I mean, Phil Jackson really believes in the basketball gods.

When the Lakers were surprised to get the number two pick in this year’s NBA draft lottery, Magic Johnson described how the “basketball gods smiled down on the Lakers” this time. (The odds were that they would get the fourth rather than the second pick. In terms of probability, second pick was supposed to go to the Knicks, a team that has been phenomenally unlucky these past years, all things considered.) During game seven of the 2013 NBA Finals, Miami Heat’s Shane Battier—a self-proclaimed believer in the basketball gods—“felt that they owed [him] big time” during his game, especially since “a bunch of shots in San Antonio […] went in and out.” Battier was, in other words, asking for karmic justice, for the basketball gods to rebalance the scales.

Along this line of logic, there is an expectation of punishment as well as compensation when it comes to the basketball gods. Hubris, for instance, can have its consequences. In a game against the Hornets, Celtics’ coach Doc Rivers blamed his team’s loss on premature cockiness: “I believe in the basketball gods. When you mess with the game, the game messes you up.” And so they lost—whether due to hubris or otherwise, perhaps it’s always less painful to imagine that such things are partly out of one’s control.

Like astrology, the discourse of karma surrounding basketball narrativizes what cannot otherwise be quantified, no matter how complex the quantifications. It reroutes instances of chance into one of narrative. The Warriors—both as a team and individually—are a goldmine for memorable anecdotes and good storytelling. Peter Guber, co-owner of the Warriors, went so far as to deploy an Old Testament analogy during Tuesday’s trophy presentation—“Forty years through the desert to now, it’s a long journey but they made it”—as though the team had been a consistent entity throughout this odyssey. Analytics might help with anticipating games and setting up plays, but talking about them rests not in the system of per-minute performance probability, but on the scale of narrative clichés, poetic justice, magical thinking.